COVID Risk Calculations

There are too many variables to make generalized calculations.

A front-page story in yesterday’s NYT, “Is Covid More Dangerous Than Driving? How Scientists Are Parsing Covid Risks.” demonstrates how challenging public health policy can be.

The setup:

Like it or not, the choose-your-own-adventure period of the pandemic is upon us.

Mask mandates have fallen. Some free testing sites have closed. Whatever parts of the United States were still trying to collectively quell the pandemic have largely turned their focus away from community-wide advice.

Now, even as case numbers begin to climb again and more infections go unreported, the onus has fallen on individual Americans to decide how much risk they and their neighbors face from the coronavirus — and what, if anything, to do about it.

For many people, the threats posed by Covid have eased dramatically over the two years of the pandemic. Vaccines slash the risk of being hospitalized or dying. Powerful new antiviral pills can help keep vulnerable people from deteriorating.

But not all Americans can count on the same protection. Millions of people with weakened immune systems do not benefit fully from vaccines. Two-thirds of Americans, and more than a third of those 65 and older, have not received the critical security of a booster shot, with the most worrisome rates among Black and Hispanic people. And patients who are poorer or live farther from doctors and pharmacies face steep barriers to getting antiviral pills.

We’re long past the point where I have a lot of sympathy for people who haven’t gotten the free vaccines that the government has been begging them to get for more than a year. But, yes, there are a whole lot of people with weakened immune systems, mostly through no fault of their own. Morever, the effects of the virus differ with age and other factors.

These vulnerabilities have made calculating the risks posed by the virus a fraught exercise. Federal health officials’ recent suggestion that most Americans could stop wearing masks because hospitalization numbers were low has created confusion in some quarters about whether the likelihood of being infected had changed, scientists said.

“We’re doing a really terrible job of communicating risk,” said Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “I think that’s also why people are throwing their hands up in the air and saying, ‘Screw it.’ They’re desperate for some sort of guidance.”

While I agree that we’ve done a poor job of breaking down risk calculations, I’m skeptical that it much matters. We couldn’t get people to wear masks when the disease was at its peak and before vaccinations were available. And many experts have argued that this very exercise—looking at risk from the standpoint of the individual rather than the collective—is the biggest challenge in getting people to act responsibly.

To fill that void, scientists are thinking anew about how to discuss Covid risks. Some have studied when people could unmask indoors if the goal was not only to keep hospitals from being overrun but also to protect immunocompromised people.

Scientists might be doing that but public health leaders aren’t. We made the switch from tracking spread to tracking hospital capacity precisely because we were never going to get spread levels down to levels that made it “safe” for immunocompromised people to go around maskless and people simply were no longer willing to put up with endless masking.

Others are working on tools to compare infection risks to the dangers of a wide range of activities, finding, for instance, that an average unvaccinated person 65 and older is roughly as likely to die from an Omicron infection as someone is to die from using heroin for a year-and-a-half.

But how people perceive risk is subjective; no two people have the same sense of the chances of dying from a year-and-a-half of heroin use (about 3 percent, by one estimate).

Indeed, I would have guessed the risk from sustained heroin use higher than that. But, then again, I’m skeptical that the rate for heroin addicts as a group tells us all that much; presumably, one’s risk varies based on frequency of use, dosage, the purity of the product, and all manner of other factors.

And beyond that, many scientists said they also worried about this latest phase of the pandemic heaping too much of the burden on individuals to make choices about keeping themselves and others safe, especially while the tools for fighting Covid remained beyond some Americans’ reach.

“As much as we wouldn’t like to believe it,” said Anne Sosin, who studies health equity at Dartmouth, “we still need a society-wide approach to the pandemic, especially to protect those who can’t benefit fully from vaccination.”

Again, we tried that for two years. People simply aren’t going to put up with restrictions based on worse-case scenarios. Regulations based on the effects on an 87-year-old with a lung transplant are going to be very hard, indeed, to enforce on healthy 23-year-olds.

Still, with far more immunity in the population than there once was, some epidemiologists have sought to make risk calculations more accessible by comparing the virus to everyday dangers.

The comparisons are particularly knotty in the United States: The country does not conduct the random swabbing studies necessary to estimate infection levels, making it difficult to know what share of infected people are dying.

Dr. Jetelina, who has published a set of comparisons in her newsletter, Your Local Epidemiologist, said that the exercise highlighted how tricky risk calculations remained for everybody, epidemiologists included.

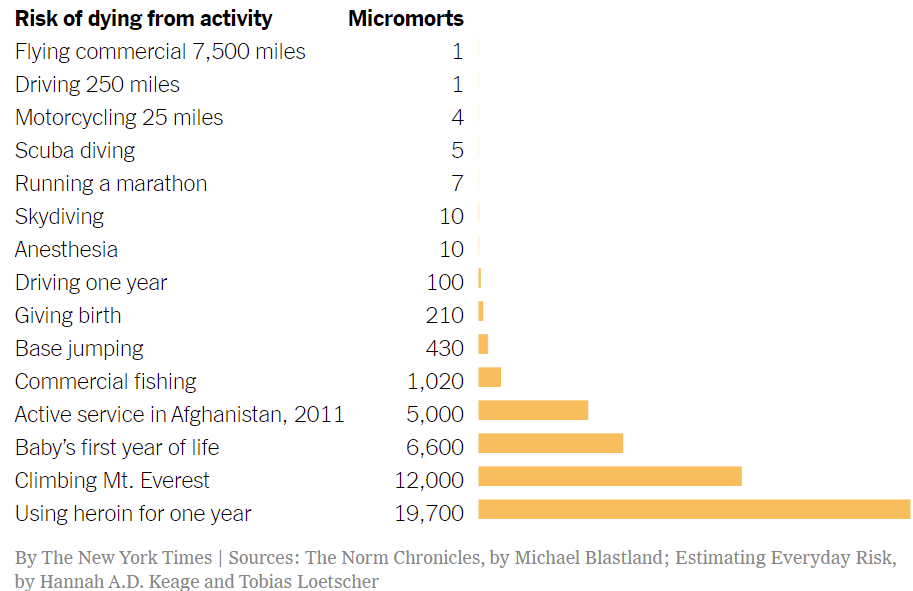

For example, she estimated that the average vaccinated and boosted person who was at least 65 years old had a risk of dying after a Covid infection slightly higher than the risk of dying during a year of military service in Afghanistan in 2011. She used a standard unit of risk known as a micromort, which represents a one-in-a-million chance of dying.

Here’s a chart based on her calculations:

But, again, this is trickier than it looks.

Presumably, the deaths from running a marathon numbers are based on deaths during marathons. It would be much higher, indeed, if we forced people who hadn’t trained and qualified to run a marathon to run 26 miles. The risks from driving, motorcycling, or skydiving depend on one’s behavior, equipment, and environment. The risk of dying in Afghanistan surely depended on one’s occupational specialty, location, and time period. Of the activities in the chart, then, I’d guess that flying commercial and receiving anesthesia are the only ones that can truly be normalized

And, of course, the scientists trying to figure all of this out are well aware of that.

But her calculations, rough as they were, included only recorded cases, rather than unreported and generally milder infections. And she did not account for the lag between cases and deaths, looking at data from a single week in January. Each of those variables could have swung estimates of risk.

“All of these nuances underline how difficult it is for individuals to calculate risk,” she said. “Epidemiologists are having a challenge with it as well.”

For children under 5, she found, the risk of dying after a Covid infection was about the same as the risk of mothers dying in childbirth in the United States. That comparison, though, highlights other difficulties in describing risk: Average numbers can hide large differences between groups. Black women, for example, are almost three times as likely as white women to die in childbirth, a reflection in part of differences in the quality of medical care and of racial bias within the health system.

And even that vastly understates the challenge. We might be able to calculate a generic “risk of a child under 5 dying from a Covid infection” statistic but it would be meaningless. The risk of any given 5-year-old dying from Covid would presumably be a function of where they live, what activities they engage in, what precautions they’re required to take, their baseline health, their access to medical care, and a host of other factors that don’t immediately spring to my non-expert mind.

Cameron Byerley, an assistant professor in mathematics education at the University of Georgia, built an online tool called Covid-Taser, allowing people to adjust age, vaccine status and health background to predict the risks of the virus. Her team used estimates from earlier in the pandemic of the proportion of infections that led to bad outcomes.

Her research has shown that people have trouble interpreting percentages, Dr. Byerley said. She recalled her 69-year-old mother-in-law being unsure whether to worry earlier in the pandemic after a news program said people her age had a 10 percent risk of dying from an infection.

Dr. Byerley suggested her mother-in-law imagine if, once out of every 10 times she used the restroom in a given day, she died. “Oh, 10 percent is terrible,” she recalled her mother-in-law saying.

While that was a perfectly effective way of explaining how often “10 percent” is, it was a mind-bogglingly poor way of explaining what a 10 percent risk is. If there’s a 10 percent risk of 69-year-olds dying from Covid, it means 9 in 10 won’t die from Covid. The bathroom analogy makes death sound inevitable because it’s a ten percent risk taken ten times a day every day.

Dr. Byerley’s estimates showed, for instance, that an average 40-year-old vaccinated over six months ago faced roughly the same chance of being hospitalized after an infection as someone did of dying in a car crash in the course of 170 cross-country road trips. (More recent vaccine shots provide better protection than older ones, complicating these predictions.)

That’s much more helpful. Why, we have millions of long-haul truckers who make their living taking precisely that sort of risk. And, while truck driving is one of our most hazardous vocations, we don’t tend think of the risks they take as unmanageable. We do attempt to make the job safer by regulating training, safety equipment, sleep deprivation, intoxicating substances, and the like. But, crucially, we don’t excessively burden non-truck drivers as a means of mitigating the risks of that line of work.

For immunocompromised people, the risks are higher. An unvaccinated 61-year-old with an organ transplant, Dr. Byerley estimated, is three times as likely to die after an infection as someone is to die within five years of receiving a diagnosis of stage one breast cancer. And that transplant recipient is twice as likely to die from Covid as someone is to die while scaling Mount Everest.

Yet roughly 900 people chose to try to climb Everest every year. And, indeed, while the submitting success rate has steadily increased, the death rate has held remarkably steady at 1 percent—mostly from unpredicted severe weather episodes.

And yet some are calculating as though we can eliminate risk.

With the most vulnerable people in mind, Dr. Jeremy Faust, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, set out last month to determine how low cases would have to fall for people to stop indoor masking without endangering those with extremely weakened immune systems.

He imagined a hypothetical person who derived no benefit from vaccines, wore a good mask, took hard-to-get prophylactic medication, attended occasional gatherings and shopped but did not work in person. He set his sights on keeping vulnerable people’s chances of being infected below 1 percent over a four-month period.

To achieve that threshold, he found, the country would have to keep masking indoors until transmission fell below 50 weekly cases per 100,000 people — a stricter limit than the C.D.C. is currently using, but one that he said nevertheless offered a benchmark to aim for.

It’s quite probable that we’ll never achieve that rate. And, again, healthy, vaccinated people simply aren’t going to put up with restrictions based on immunocompromised geriatrics indefinitely.

Here’s my very simple calculation:

If you don’t get infected, your risk of death from COVID is zero. If you wear a good mask, your risk of infection is lower.

I don’t know whether this typical or atypical for viral infections but the age difference in risk for COVID astounds me. At one point I was going down the statistics rabbit hole and learned that someone age 70 was 1000 times as likely to die of COVID then someone age 7. And while an 18-25 year old sees their risk drop by a factor of 20 or better when they get vaccinated, at over 65 that drops to less than 5.

@Kathy: My personal calculation is that we are all very likely to get COVID in the next 2-3 years. If you are faxed and boosted you have less chance of dying from it than the seasonal flu. SNL had Faux Fauci saying the truth out loud: if you are not vaccinated by now then your death or long COVID is on you. We, as a society, are ready to stop protections put in place for anti-vaxers and the immuno-compromised. Sucks for the latter, but tough nuts for the former.

@MarkedMan:

If we let down all precautions and take all risks, then, yes, we’ll all get COVID.

And if you die of a breakthrough infection, it won’t matter much how low the risk for vaccinated and boosted people were, or how many covidiots join you in the grave.

@Kathy:

In my estimation COVID is here to stay. It’s like seasonal flu. We don’t mask and lockdown for seasonal flu and we won’t for COVID because for the vaccinated it is no more deadly than the flu. The unvaccinated are 99% there by choice.

Many of these epidemiologists and virologists are flailing about and not providing information that is cogent to the typical person. The first thing I noticed when reading that article earlier was that the CDC has stated that case rates are rising in the northeast. Well, what the h$ll does that mean, northeast could mean New England, it may include the NYC metro, maybe NJ and eastern PA. Knowing case rates are rising in a fifth of the country isn’t helpful.

Info needs to be far more granular, people really only care about and will act on info from their immediate area. Only then can you begin to measure risk. The best way to notify the public about possible risk levels would be for local public health officials to place roadside advisory signs giving the local infection levels, something similar to what you see regarding air quality. Weather websites could also help by placing that info on the community forecast page. When I check the weather for Hampster, I can see what the covid infection rates are and recommendations for personal mitigation. The rest is noise.

@Sleeping Dog:

The blame for that falls on the journalist who wrote that article, not the CDC which provides very specific information.

Agreeing with Kathy on risks and will add the risk of long Covid. I find wearing a mask less onerous than being seriously disabled for the rest of my life. Those risks are known very poorly – seem to be somewhat less with vaccination, but still significant.

And then there are the longer-term risks, which we have no idea of. People are now becoming disabled from cases of polio that they had in the 1950s. I would bet that there will be an epidemic of something – early-onset dementia, maybe – in 30 years among people who had “mild” Covid, but I won’t be around to collect.

The risk of death remains exactly where it has always been: 100%. It’s not an if? it’s a when? and a how? Something’s gonna kill me. Heart disease, cancer, covid. . . 100%.

Knowing this the question becomes how should one live? Is the goal to maximize lifespan at any cost? Is the goal to live an enjoyable life? An interesting life? Perhaps a consequential life?

When I was on the run it wasn’t about death but capture – a fairly good stand-in for death if we want to get metaphorical. I had a number of choices to make. I broke contact with my past completely. I never got behind the wheel of a car. Those two choices reduced the threat very significantly, but I still had the problem of chance recognition. To address that I could either hide in my room, or decide just how much risk to accept. In the end I spent two decades worrying about something that never happened.

Nowadays I don’t exercise, but I do control my cholesterol and blood pressure with meds. I don’t smoke cigarettes, do smoke cigars. I don’t use heroin or coke or meth, do use weed. I don’t get drunk, but I do drink. I drive a convertible, probably the safest convertible you can get, but it’s not a Humvee. My home security is pretty good, but not insane. I have blood work once a year and a colonoscopy every decade, but I’ve avoided the whole ‘executive physical’ thing. You have to find a level of risk that still lets you live a life.

I don’t think the winning move is to have a long life, but to have a good life, and a good life is not one dominated by fear of death.

@Michael Reynolds: I use an umbrella when I go out in the rain, not because I fear the rain, but because I don’t want to get wet. Likewise, I use a mask in public settings not because I fear death or disability, but because I’d like to live a good life as long as possible.

The accusations of fear are getting a bit old. It’s a putdown to people who don’t share your macho carelessness. (See how that works?)

@Michael Reynolds:

There’s a big difference between doing things for decades that may take 5 or 10 or 20 years off your life, if that makes life more enjoyable, and doing something a few time that takes all the years off your life within a month.

@MarkedMan:

COVID won’t be like seasonal flu, because 1) it’s not seasonal, and 2) it’s far more dangerous than the flu even if you’re vaccinated; more like a very bad flu, like H1N1 or bird flu.

@Sleeping Dog: The COVID data is readily available down to the county level.

@Cheryl Rofer:

I don’t think I accused anyone of anything, Cheryl.

It’s not ‘macho carelessness’ – I have four rounds of Moderna in my shoulder and I mask where I see high risk – it’s long experience with fear. Finding the balance is a personal thing, everyone makes their own decisions, and I’m not claiming my calculus should be yours or anyone’s. But I think it’s very likely that I have more experience dealing with fear than you do and perhaps rather than snark you might consider the possibility that because I’ve been in more dark places than you have, I may have some insight based on that very intimate and long-lasting relationship with fear.

I’m afraid of covid. I have a pro-level imagination and I suspect I’ve spent more time contemplating my own death, and the deaths of loved ones, and played those scenarios out in more iterations and in more gruesome detail than most sane people. But as I’m sure you’ve heard fear is the mind-killer, the little death that brings total obliteration. (Feel free to quote me on that). I’m not unafraid, I face the fear and assess it and decide for myself how to respond to it. I willingly assume risk as the price of defining my own life.

While concern for my own well-being are certainly relevant, I find I also include the welfare of people I associate with in my calculations. I don’t want to get them sick. Wearing a mask will reduce that chance, too. I could be walking around shedding virus for several days and not know it.

The exchange above between Michael and Cheryl interests me greatly, in no small part because that sort of thing has happened to me.

I read Michaels initial comment as an expanded suggestion based on personal experience and example. It was also fairly vulnerable. I don’t think Michael much enjoyed his time on the run.

And Cheryl reads it as a command, in part because there are no words like “possibly”, “maybe”, “perhaps”, “what if”, or “suggestion” in it. Or very few.

Neither person is wrong. I am not taking sides. This happens to me a lot, even with family members, who I am making suggestions to, but instead of considering my suggestion, they get all “Don’t Order Me Around!” which I wasn’t, but they thought I was.

I like to explore why this might be. I recall including words like “maybe”, “perhaps” and “I think” in my essays in 9th grade, only to have my teacher Mr. Eames, cross them out with red ink and say “weak”. Mr. Eames was an English teacher and wore cardigans, so not the most macho of guys. I wonder if women get the same feedback. Do women english teachers give that feedback?

Are there other factors, other training involved here? It interests me a lot.

@MarkedMan:

Covid or any data that needs to be researched is useless to people trying to manage already hectic daily lives.

@Michael Reynolds:

La petite morte.

1M dead.

Both cars and covid are pretty endemic, and cars get about 30,000 people a year in this country. Covid is a way, way greater risk.

And that’s not counting the costs of long covid at all.

I know The NY Times editors just picked a flashy headline, but they picked a very poor example. It’s not even close.

It really would be convenient if they would just shut up and die already.

I get it, it’s like when you see a homeless person and think “there’s nothing that I can do to change the underlying conditions of society that have made it so that so many people are living paycheck to paycheck and only need a medium sized crisis to knock them to the curb, it sucks but there’s nothing to be done, at least not without building more housing and changing the character of the neighborhood, oh look a squirrel.”

We live in a country founded on rugged individualism, and those who aren’t rugged enough are just the price of freedom.

We make these trade offs all the time — the spotted owl or jobs, human rights or cheap gas, ten dead people over there or one dead person over here, seven dead people over there or a modest inconvenience.

Just own up to it — the elderly and infirm can die, and the rest of us will hopefully die of something more pleasant than suffocating while our lungs slowly liquify (or clot up… or both… I’m a little unsure, I know there are clots, and I know there’s a lot of blood, and it’s not a great time)

The elderly and infirm simply aren’t worth the effort. Honestly, it’s a little surprising modern medicine kept them alive long enough to even see a pandemic. They should be grateful.

There are limits to what we can do. I’m just surprised that this country has decided those limits are so low.

@Sleeping Dog:

I’m not trying to give you grief, but this has been on the main page of the WaPo website since early in the pandemic. You don’t need a subscription to access it. The default is the statistics for the country as a whole, but all you have to do is select your state in the drop down box and it switches to statistics for that state. I believe that if you bookmark it like that it will stay that way when you click on your bookmark again. Once you are at the state level, each section (Cases, Hospitalizations, Deaths, Vaccinations) has a county by county list at the end.

@Gustopher:

It depends on what you mean by “this country”. The government and many, many individuals have saved millions of lives by “flattening the curve” and getting a vaccine into the arms of everyone who wants one in record time.

Given the nature of this virus we were never going to make it go away completely. Look at China, for crying out loud! Mandatory universal vaccination, massive state repression, a willingness to shut down entire cities, including one with a population of 28M! And even they can’t stop it from spreading. COVID is now a reality, just like seasonal flu or hundreds of other things. And yes, if an immunocompromised person, even a vaccinated, one gets COVID, or the flu or a myriad of other transmissible diseases, they are going to have a rough time and may die. It is a terrible reality but I don’t think 100% masking now and forever is a viable option.

@MarkedMan: I think that the message was more along the lines of too busy to/can’t be bothered with than it was about not being able to find information.

@Gustopher:

To take the analogy on, think of vaccines as seat belts and airbags.

Yes, you’re less likely to be badly injured or killed if you wear a seat belt and ride a car equipped with airbags, but this doesn’t mean you should drive recklessly.

@MarkedMan:

But think of the lives saved not just from COVID but also flu among the elderly and immunocompromised, as well as the millions of extra hours of active and productive life generally by lowering the incidence of even the common cold.

I just got to say I am really tired of that load of horse shit. Fear is what keeps a person alive. It hones ones awareness and reactions to a razors edge. I’ve done shit that I’d be willing to bet 99% of people have never imagined, danced cheek to cheek with death, whispering sweet nothings in my ear.

Was I scared? You dawgdamned right I was. Afraid I might die or even worse, afraid I might live while somebody else died. But I didn’t, and I managed to not get anybody else killed. And at least part of the reason is because my fear kept me sharp, aware, and focused.

@Kathy: Yes. In normal years, for whatever reason, I could get up to 6 colds, and some of them would be so rough that they’d overlap. The last few years? Two fairly minor colds. So while I’ve never thought I’d die from a cold, it’s been nice to not be sick all of the time. I can’t say how much of that is masking vs. people staying home vs. everyone washing their hands better, but I’d be surprised if the masking had zero effect.

Having said that, I’m not sure I’ll bother to wear a mask much in the future, for colds or covid. Maybe if there’s a cold/flu outbreak here I will.

@reid:

I plan to mask whenever I hear anyone at the office as much as sniffle, or when going to the movies, or even to a crowded place. I very much like the idea of never again catching the common cold.

They tend not to hit me hard, but when I have one I keep waking up two to four times a night. Either short of breath or with a dry mouth, both due to a stuffed nose.

@MarkedMan:

There are far, far more gradients than masking forever, 100% of the time.

Critical businesses — pharmacies, groceries, doctors offices — should be masked. Places where the elderly and compromised cannot avoid.

Masking requirements going back in place with CDC community transmission levels — over 200 cases per day per 100,000, to pick a number out of a hat. A number which would have my county masking up again soon, if not already.

There’s a whole range of possibilities between laminating everyone and saying “Eh, fuck it, we’re done.”

@Jay L Gischer:

I wear cardigans. Cardigans are punk as fuck.

@Gustopher:

I plan and just assume I am going to mask up in a grocery store, bank, pharmacy, office from here on out.

To protect myself and others. Plus, it ain’t no big thing. It isn’t a hassle except for fogged glasses every now and again.

I no longer work so my exposure is an hour or two a week. Easy frickin peasy.

If somebody else thinks I am over-reacting or being over-cautious, well, fuck em. It ain’t their business! I don’t care what they think. It harms no one. My business, fuck off.

@de stijl: If anybody asks you about your mask, just tell them you tested positive for Covid and it’s to protect them, not you. I hear it works pretty well. 😛

@Jax:

I deal with Social Anxiety Disorder, agoraphobia, avoidance, and just being a general-ass weirdo. (I’m not *that* weird, not Joaquin Phoenix weird, more like Willem Dafoe weird. Perfectly personable and presentable.)

Wearing a mask is not a bother to me at all. The opposite. It is a boon. Made my life way better. Felt less judged.

Offer somebody who copes with SAD the opportunity to wear a mask in public and be subltly socially rewarded for doing so and you’re going to get a 100% uptake rate on that offer.

Offer an agoraphobe a situation where self-isolation is the socially responsible thing to do in a pandemic. Again, 100% uptake.

This will sound extremely bizarre, but Covid lock down and masking made me feel freer, less constrained, and generally happier.

My punkish defiance stated above might have a tinge of raw selfishness. A bit. Just sayin.

@Gustopher:

For the print edition, they went with the more generic “Weighing Risks As Virus Threat Becomes Norm.” But it’s just a condensed headline based on two different examples from the chart.

@Gustopher:

There are pretty much zero examples where we burden the rights of the whole society to protect the health of a small subset. It would be far more efficient to have special hours for high-risk folks.