Daniel Ellsberg Wants More Leaks

The Pentagon Papers guy laments that there are too few like him.

NYT editorial board member Alex Kingbury interviews 91-year-old Daniel Ellsberg and discovers that “The Man Who Leaked the Pentagon Papers Is Scared” about the possibility of a nuclear war and that we’re not doing enough to combat climate change. I find that less interesting than his expansionistic view of leaking government secrets.

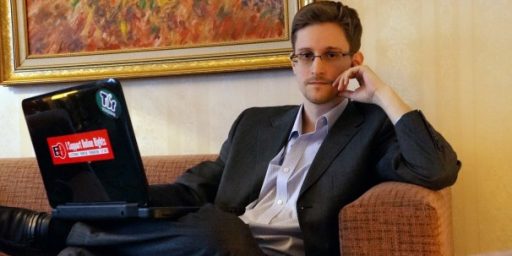

Q. The number of people with the security clearances to view classified material has expanded, perhaps exponentially, since the leak of the Pentagon Papers, and I wonder, aside from a few people like Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, why haven’t there been more Dan Ellsbergs? Why aren’t there more people who, when presented with evidence of something that they find morally objectionable, disclose it?

A. Why aren’t there more? It’s a question I’ve often asked myself. Many of the people whistle-blowers work with know the same things and actually regard the information in the same way — that it’s wrong — but they keep their mouths shut. As Snowden said to me and others, “Everybody I dealt with said that what we were doing was wrong. It’s unconstitutional. We’re getting information here about Americans that we shouldn’t be collecting.” The same thing was true for many of my colleagues in government who opposed the war. Of course, people are worried about the consequences.

I find it fascinating that neither Kingsbury nor Ellsberg distinguish between the actions of Ellsberg, Snowden, and Manning. Ellsberg was, at the time he leaked the Pentagon Papers, a rather seasoned official who tried and failed to get the truth out through proper channels. Only after key Senators refused to do anything did he go to the press and, even then, he was careful to release only documents that showed the malfeasance he was highlighting. Snowden was more reckless, neither attempting to go through channels nor being particularly careful about what he released—but he was at least highlighting a particular program. Manning actually enlisted with the intention of committing espionage; he simply released documents willy-nilly.

Before my case and the Obama administration’s prosecutions of whistle-blowers, they needn’t have been worried about going to jail. But apart from that, they fear losing their jobs, their careers, risking the clearances on which their jobs depend. People who have these clearances have often invested a lifetime in demonstrating that they can be entrusted to keep secrets. That trust becomes a part of your identity, which it is difficult to sacrifice, so that one loses track of a sense of higher responsibility — as a citizen, as a human being.

I think this is all true. But it’s also true that the overwhelming number of people who have security clearances actually access very little secret information and almost none are privy to the sort of secrets Ellsberg himself had. (He had been in senior advisory positions in government and was back at RAND working on a top secret project commissioned by Secretary of Defense McNamara.) And the relatively few people who encounter troubling information are acculturated to a chain of command, operating on the presumption that those senior to them are acting under good intentions and sound legal advice.

Q. We tend to think of the classification system as a system of protection. But you sometimes talk about it, and I think correctly, as a system of control.

A. That is what it is. It is a protection system against the revelation of mistakes, false predictions, embarrassments of various kinds and maybe even crimes. And then the secrecy system in its application is predominantly to protect officials, administrations from embarrassment and from accountability, from the possibility that their rivals will pick these things up and beat them over the head with it. Their rivals for office, for instance.

This is utter bullshit. To be sure, we reflexively over-classify for a variety of reasons. (More on that later.) But the amount that’s intentionally covering up mistakes and the like is less than a rounding error. Indeed, essentially none of it is classified by people at that level; it’s almost all done at the operational levels and below.

Q. How should the average reader understand the difference between the importance of a risotto recipe that was disclosed by the Russian hack of John Podesta’s email account and serious secrets like those disclosed by Snowden? Steven Aftergood at the Federation of American Scientists, who studies secrecy, for instance, once called the indiscriminate disclosure of military files by WikiLeaks a kind of “information vandalism.”

A. I disagree with Steve. I think he greatly underestimates the amount of overclassification. The media as a whole has never really investigated the secrecy system and what it’s for and what its effects are. For example, the best people on declassification outside the media, the National Security Archive, month after month, year after year, put out newly disclosed classified information that they have worked sometimes three or four years, 10 years, 20 years to make public. Very little of that was justified to be kept from the public that long, if at all. An expert estimated in Congress in 1971 that 5 percent of classified information met the criteria for secrecy at the time it was classified, and after a few years that decreased to half of one percent.

I’ve never met Aftergood but have followed his work for at least the last twenty years. He’s painfully aware of overclassification, as are any of us who have clearances. I agree with Ellsberg that it’s too hard and takes to long to de-classify what has been classified. But relying on 52-year-old analyses is rather silly. Further, all of the incentives point in the direction of classifying—but not for the nefarious reasons Ellsberg cites.

Mostly it’s simply CYA: the penalties for failure to classify that which ought be classified are much higher than for the reverse (essentially none). Additionally, there are powerful bureaucratic incentives to classify. Having possession of highly classified information makes you more valuable. And decisionmakers are, for weird psychological reasons, far more likely to pay attention to Information That Only Very Special People Get to See than they are to that which can be gleaned from open sources.

Ellsberg is, quite naturally, anchored to his own experiences with the Vietnam War, the lies told in its advancement by the Johnson administration, and the overzealous prosecution of his leak by the Nixon administration. He’s 91 years old and has been diagnosed with terminal cancer, with perhaps just months to live.

I believe his actions in leaking the Pentagon Papers, while violating his oath, were legitimately motivated by patriotism. Ultimately, though, I believe that the system for protecting state secrets, established in law by Congress and overseen by an elected President and his Senate-confirmed officials, is a necessary but imperfect system. We can’t have every idiot private with a security clearance act as a personal arbiter of our nation’s secrets.

Last paragraph is incomplete?

@Michael Cain: Fixed. The coffee-damaged laptop suddenly had a mind of its own.

True enough, but assessing whether a release is damaging or justified happens post release. I was an undergrad when the Pentagon Papers were released and was an avid consumer of not only the papers, but the political and legal circus that followed. As I recall, even among those who agreed that the release of the Papers was valuable in informing the public of the deception that was perpetrated by the government, few went so far as to praise Ellsberg.

It was a fascinating time walk by the newsstand and see the Times headline, so you bought the paper. That afternoon Nixon got an injunction against publication v. the Times. The next morning it was the Boston Globe, Nixon rinse and repeat. The next morning it was the Washington Post and it feels like groundhog day.

Official DC runs on secrets and gossip. Classified is just the “upper” level of the gossip. I was once brought it a brewing scandal “when the industry finds out” only to discover the scandalous information was from a Boston newspaper article. See it hadn’t appeared in the NY Times or WaPo so it was stil a secret in DC terms for the gossip mongering.

And now 20 years or so, the DOJ was going after a guy for export control violations for sending publicly distributed brochures from a conference that was open to the public to China. I told my GC contact that if they won, I would be recommending my agency deny access to all Chinese national scientists since we too had publicly available information about controlled technology laying about in our facilities which visiting scientists might read or be briefed on by an employee.

Now imagine the foolishness when something has “classified” across the cover.

@Sleeping Dog: IIRC early in WWI the British set up a committee to draft a statement defining their war aims. They were still meeting, without result, at the Armistice.

The real secret in the Pentagon Papers was that there was no secret. Ellsberg et al had been charged with reviewing the history of the war to find the reasons we were fighting. They couldn’t find any. It just happened. That was the message of The Best and the Brightest, that the group dynamics were such that none of these very smart guys ever raised his hand and asked, “Why?”

I recall some high official under W. Remarking that he had sat in on all the meetings and they went from discussing the possibility of invading Iraq, to contingency planning, to planning, to execution without anyone ever saying, “We’ve decided to do it.”

That’s because the decision to invade Iraq was made before the discussions on the possibility. The possibility discussions were window dressing to bring aboard those who hadn’t already drunk the cool-aid.

Sure because leaking information to people that have neither the time and/nor the sophisticated to understand the context of the leaks let alone the complexity of the issue being leaked achieves what exactly again?

I know! It gets clicks, like, and retweets… exactly the outcome the public is clamoring for journalists to deliver.

The truth is… journalism has no market. It’s mutually exclusive of entertainment…which is what there is a market for. More leaks will not achieve any different outcomes than less leaks.

The infotainment news driven “conversation” is nearly always on the wrong subject. Even when a important topic has media attention, it’s framed in ridiculous ways that make problem-solving impossible.

Chris Rock did an interview with an interesting observation he had regarding crowds. He said it didn’t matter the crowd, you take the IQ of the smartest person in the crowd and divide it by the number of people in it. Which meant he could tell more nuanced, Storytelling jokes at a small club in Alabama than he could playing Madison Square Gardens.

There is too much media, and too many voices having too many conversations with too many people. The “conversation” is only going to devolve until there is a course correction in the size of the media ecosystem.

@JKB:

Interesting. So I’m sure you were outraged when you learned that one of “Hillary’s Classified Documents” that the trumpers are endlessly going on about was an article from The Washington Post and the “Classified Email Exchange!!!” involved a staffer asking if she wanted to respond to it? I’m sure you are equally outraged, because you are a fair minded weigher of the facts.

“Ellsberg is, quite naturally, anchored to his own experiences with the Vietnam War, the lies told in its advancement by the Johnson administration, and the overzealous prosecution of his leak by the Nixon administration.”

Well, thank God that no administration since Nixon’s has ever told lies about anything important.

@JKB: Anyone who has held a clearance knows that even media publication of a classified document does not declassify it.

Snowden also got his NSA job for the specific purpose of leaking. And he wasn’t just “reckless” – he intentionally hoovered up all information he could from the NSA databases he had access to. All of it and took it out of the country. And once he got to Hong Kong, he ended up disclosing some to the Chinese for safe passage out and into the loving arms of Putin’s FSB. He claims he didn’t give the Russians anything and that everything he took is quite secure.

I would have some sympathy for Snowden if he had acted as Ellsworth did, but he did not.

As far as Ellsberg goes, we have way more leaks, they just come from “anonymous” officials. Washington is an information sieve populated by courtiers who see selective and self-serving leaking as more important than information security whether done for personal ego or as attempts to influence policy.

And our security today is, ironically, much crappier than it was during the Cold War. And the classification EOs and related regulations fundamentally changed during my career from 1993 to 2017. When I first came in, there was still very much a Cold War mentality in which security was taken much more seriously. And when I joined that was 20 years after Ellsworth and a lot had changed since the 1970’s, in large part because of what he did. His contemporary knowledge of how our system of national defense secrets is – at best – dated.

During my time, there were several reforms including on declassification, but as James notes, it’s a difficult problem. There was also the move from paper to electronic records, which caused an explosion in the amount of information sitting on classified systems and exacerbated the declassification problem. In the paper days, everything was much easier to manage.

Most of the problem with “overclassification” today comes from the explosion in information combined with how information is segregated on different computer systems. If you look at Manning’s leaks of diplo communications and the regional incident database, you’ll see there’s a lot of unclass info on there. But the database is on a classified system. It’s just not possible to keep all unclassified information on an unclassified computer, secret info on a secret computer, and SCI info on an SCI computer. These systems are air-gapped for good reason.

And the government tried in the 1990’s to make multi-classification systems that could segregate information on the same system and succeeded in a few cases, but these were expensive bespoke unix systems required extensive contractor support. By this time the government was moving to desktop PCs and Windows because it’s so much cheaper – those can’t do what the bespoke systems could, so the result is tiered systems with air-gapped networks where information could only flow uphill.

Anyway, that’s probably too much inside baseball. I think fundamentally the reason there aren’t the kinds of leaks that Ellsberg did is because so much stuff already leaks. And administrations understand this and are less inclined to do stupid stuff that will get them in political trouble. And secondly, I think there is much better oversight and better procedures than there used to be, and a lot more bureaucracy which makes cowboy actions more difficult. And also, a lot more lawyers.