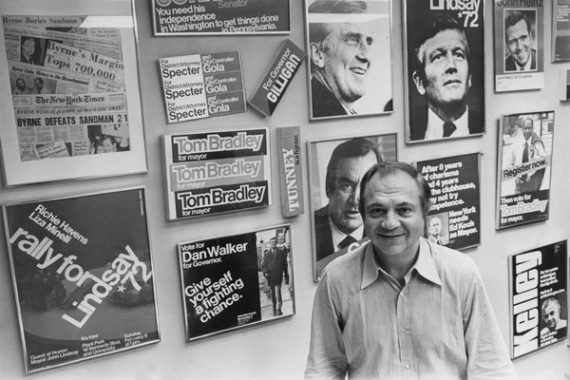

David Garth, Pioneer Political And Campaign Consultant, Dies At 84

David Garth, who served behind the scenes of American politics for some four decades and helped elect Governors, Mayors, and Senators from the 1960s through the 2000s, has died at the age of 84:

David Garth, a pugnacious and indefatigable pioneer of the political commercial, who helped elect governors, senators and four New York City mayors, died on Monday at his home in Manhattan. He was 84.

His nephew Jonathan Rosenbloom confirmed the death, attributing it to a long, unspecified illness.

Mr. Garth never sought nor accepted public office himself, but he wielded immense behind-the-scenes influence on New York government through his successful clients, including Gov. Hugh L. Carey in the 1974 election.

Mr. Garth was “one of the two people most responsible for the central role of television in modern American politics,” said Robert M. Shrum, a Democratic strategist who worked with him, singling out Charles Guggenheim, an adviser to Robert F. Kennedy, as the other.

Mr. Garth’s political ads were characterized by an unusual feat of political jujitsu, one in which he would elevate potential liabilities into an asset by cajoling candidates to face a video camera earnestly and do something daring, even distasteful, in the ego-driven scrum of a campaign: admit their mistakes.

Superimposed on his cinéma vérité commercials was a welter of printed information (a technique that he claimed he originated to cover a scratched videotape).

Mr. Garth was renowned for elevating virtual unknowns into upset victors, beginning with Representative John V. Lindsay in his race for mayor of New York in 1965. Mr. Garth orchestrated New York’s first television-based campaign on Mr. Lindsay’s behalf, taking advantage of his client’s good looks.

In 1977, when Mario M. Cuomo was running for mayor against Mr. Garth’s come-from-behind creation, Edward I. Koch, Mr. Cuomo sardonically demanded: “What hath Garth wrought?” What Mr. Garth wrought that year, after making his candidate shed 10 pounds and fusty three-button suits, was Mr. Koch’s election. Years later, Mr. Cuomo would recruit Mr. Garth for one of his own campaigns for governor.

His signature style combined fierce competitiveness, combustible energy and relentless loyalty. Indeed, he was the model for the media hustler in Robert Redford’s film “The Candidate.” (Mr. Redford wanted Mr. Garth to play the role himself; when he declined, a volcanic Allen Garfield was cast instead.)

Mr. Garth handled his share of losers, but his roster of winners was impressive. He claimed a batting average of .730 — “a bit better than Ted Williams’s Major League record of .400,” he said.

A liberal Democrat, Mr. Garth generally worked for liberal or moderate candidates: He cut his political teeth on Adlai E. Stevenson’s short-lived 1960 presidential race; he went on to represent Governors Carey of New York, Ella T. Grasso of Connecticut, Brendan T. Byrne of New Jersey and John J. Gilligan of Ohio; as well as Mayors Koch of New York and Tom Bradley of Los Angeles.

But his clients included several Republicans: Senators Arlen Specter and John Heinz of Pennsylvania; and Mayors Lindsay, Rudolph W. Giuliani and Michael R. Bloomberg of New York. (Mr. Lindsay later became a Democrat, and Mr. Bloomberg a political independent.)

In all, the New York mayors he helped elect served 40 years.

“He helped shape New York by helping so many of us achieve higher office,” Mr. Giuliani said.

Mr. Garth also brokered Mr. Giuliani’s belated, if nonetheless pivotal, endorsement of Mr. Bloomberg in 2001. His international clients included the presidents of Colombia and Venezuela and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel.

Roger Ailes, the president of Fox News and a former political consultant himself, called Mr. Garth “a giant in the business of political consultancy.”

“He was a political guy who learned how to use television rather than a television guy who learned politics,” Mr. Ailes said. “Nobody knew New York better, and the first question in a campaign was, ‘Who’s Garth with?’ He replaced a hell of a lot of smoke-filled back rooms.”

(…)

Larry J. Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, said in an interview: “When you became a David Garth client that is how your campaign was branded. It’s almost as though the consultant mattered more than the candidate.”

A chunky 5-foot-8 and perpetually puffing on hand-rolled Brazilian rope cigars, Mr. Garth was typically feisty, planting stories about his opponents and goading the press to report them. “If I throw out five matches,” he once said, “maybe I’ll start two fires.”

He combined what Jeff Greenfield, the political commentator who worked with Mr. Garth, described as “the single-mindedness of Vince Lombardi with the subtlety of a pile driver,” and he viewed every campaign as a public fight to the death, comparing a campaign to “the arena of the gladiators.”

Mr. Greenfield recalled that “sometimes I had to remind him that it is not a violation of the First Amendment for the other guy to put on ads, too.”

Mr. Garth could sum up a campaign theme in two words. When Luis Herrera Campins was running for president of Venezuela against the ruling party, Mr. Garth devised a two-word campaign slogan that struck a responsive chord. The battle cry was “Ya Basta” — “Enough Is Enough” (or, in the New York vernacular, “Enough, Already”).

But Mr. Garth was better known for tongue-twisting slogans intended to convey a substantive message. For Mr. Carey: “This year, before they tell you what they want to do, make them show you what they’ve done.” For Mr. Koch: “After eight years of charisma and four years of the clubhouse, why not try competence?” (The charisma was a gentle jab at Mr. Lindsay, whom Mr. Garth had also helped elect.)

In 1969, when Mr. Lindsay’s re-election seemed like a lost cause, Mr. Garth; Richard R. Aurelio, the campaign manager; and Tony Isidore of the advertising agency Young & Rubicam persuaded the mayor to admit publicly that he had made mistakes performing the “second toughest job in America.” (Mr. Lindsay began: “I guessed wrong on the weather before the city’s biggest snowfall last winter, and that was a mistake. But I put 6,000 more cops on the streets, and that was no mistake.”) He was persuasive enough to win.

“Now candidates have confessionals all the time,” Professor Sabato said. “Back then, you never let them see you sweat or never admit you weren’t right.”

That was an example of what Mr. Greenfield described as Mr. Garth’s political judo, transforming a candidate’s real or perceived weakness into an asset. In the Bradley mayoral campaign in Los Angeles, he directly confronted voters’ fears that Mr. Bradley, who was black, would favor black people. As Mr. Greenfield later wrote:

“The last time I ran for mayor, I lost,” Mr. Bradley said, straight into the camera. ‘Maybe some of you worried that I’d favor one group over another. In the first place, I couldn’t win that way; Los Angeles has the smallest black population of any big city in America.’ ”

The rest of the ad went on to say that he would not want to win by appealing to racial sentiments, and he offered calming words about different groups working together. But the heart of the ad was its first message: I understand your fears, and it would not serve me politically to stoke them. What made this so unusual was that it flew smack in the face of one of the central tenets of political ad-making: Thou shalt not speak directly of politics, because this is inside baseball and voters do not like it.

Garth was the first in a long line of what has become something of a phenomenon in American politics, the celebrity political consultant. In his wake, on both sides of the aisle we would see people like James Carville, Lee Atwater, Roger Ailes, and others, who often became as famous as the candidates they worked for and who would make news whenever they decided to sign up for a particular campaign. That isn’t quite as big of a deal as it used to be, in no small part because there are so many more people who fulfill that role, but Garth was part of the first generation of a new type of campaigning in American politics that has, for better or worse, become a part of the political zeitgeist. Garth also became famous because he was among the first such consultants to realize the true power of the campaign commercial, not just at the national level but at the state and local level as well.In fact, I can remember many of the commercials run by Ed Koch and other Garth-backed candidates quite well today, even though its been some forty years since they ran. He was a true pioneer in a field when it was just starting to develop, and anyone who even pretends to be a “campaign consultant” today owes what they do in no small part to him and what he did.