Democrats Will Split Early Debates Over Two Nights

Faced with a field that could be more crowded than the Republican field in 2016, Democrats have come up with a different solution to the rather obvious problem of debate scheduling.

Late last week, Democrats announced plans to split debates into two nights:

The Democratic National Committee on Thursday unveiled the criteria for participation in the first two presidential primary debates, splitting the debates across two consecutive nights to accommodate an already sprawling field of candidates.

Party officials, anticipating a rush of candidates eager to grab a spot in the nationally televised forums, created a new set of standards that would accommodate a maximum of 20 candidates. To qualify, a candidate must either reach 1 percent in three approved polls or raise at least $65,000 from 200 donors in 20 different states. Each candidate’s slot will be selected by a random drawing.

The criteria will apply only to the first two debates, scheduled for back-to-back weeknights in June and July, allowing the committee to update its requirements as the field shifts. NBC News, MSNBC and Telemundo are sponsoring the first debate, and CNN will host the second, with specific dates and locations to be announced in the coming weeks.

In total, the committee expects to hold a dozen debates over the 2020 campaign cycle.

“Because campaigns are won on the strength of their grass roots, we also updated the threshold, giving all types of candidates the opportunity to reach the debate stage and giving small-dollar donors a bigger voice in the primary than ever before,” Tom Perez, the committee chairman, said in a statement.

Small-dollar donations have emerged as a significant metric for assessing candidates’ early strength, as some have disavowed “super PACs” that allow for unlimited sums from wealthy backers. The new debate standard, the first to include small-dollar donations, is likely to intensify the pressure for candidates, particularly those with less name recognition, to quickly lock down donors.

Even though we’re only two months into the year, it’s already apparent that there will be a large Democratic field in 2020, at least in the early stages of the race. Already we have seen campaign announcements from relatively well-known candidates such as Kirsten Gillibrand, Julian Castro, Tulsi Gabbard, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, and Cory Booker, There have also been announcements from lesser-known candidates such as South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Maryland Congressman John Delaney. Additionally, the coming weeks are likely to see announcements from Bernie Sanders, Michael Bloomberg, and Joe Biden. Other potential candidates include Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, former Attorney General Eric Holder, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, former Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe, Ohio Congressman Tim Ryan, former Texas Congressman Beto O’Rourke, Washington Governor Jay Inslee, Oregon Senator Jeff Merkeley, Massachusetts Congressman Seth Moulton, California Congressman Eric Swalwell, New York City Mayor Bill Delblasio, and many others. If all of these candidates entered the race, which seems unlikely, that would make for 23 candidates in the Democratic field, much more than were in the Republican field in 2016 and likely the largest field of candidates with some national presence in the race for a party nomination in American history. Even if they don’t all get into the race, we’re already at nine candidates and likely to get up to twelve by the middle of March when Sanders, Bloomberg, and Biden are believed to have set as the deadline for making a decision on getting into the race. Obviously, with a field potentially this large the debate scheduling is an issue

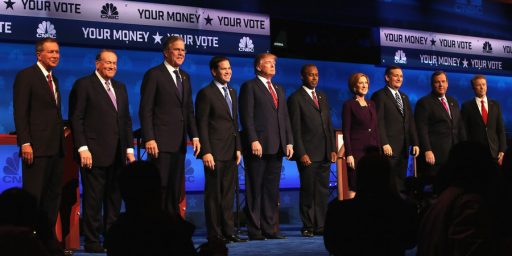

This means, of course, that Democrats looking forward t0 the 2020 campaign find themselves faced with the same problems that Republicans and their debate partners were faced with at the start of the 2016 election cycle. In that election cycle, the first debate was held in August 2016 and became notable mostly for Donald Trump’s clash with Fox News’s Megyn Kelly. At that point in the race, there were seventeen people in the race for the nomination, including former Senators, Governors, and Members of Congress. While many of these candidates were near the bottom of the field in the polls, the organizers of the early debates recognized that excluding them entirely was not practical but so was having seventeen people on the stage at the same time. As a result, they came up with the solution of dividing the debate into two events. The main debates, which aired in prime time, included the candidates leading in the polls, while what came to be called the “undercard” debate included other candidates who were further down in the polls but nonetheless arguably had resumes that demanded they not be ignored entirely. It was far from an ideal solution, but given the size of the field, it wasn’t entirely a bad idea about how to deal with an otherwise intractable problem.

The biggest problem with the undercard debate idea, of course, is that it really didn’t address the fundamental complaint of the lower-ranked candidates that they were being denied the media coverage that the participants in the “main” debate would get. In some cases, this was because some of these candidates, such as former Virginia Governor Jim Gilmore, didn’t qualify even for the undercard debate, but mainly it was because the undercard debates would typically be held before the main debate beginning around 6:00 p.m. Eastern time, a time when Americans in the eastern half of the country were still making their way home from work and Americans in the western half of the country were still at work. The main stage debates, meanwhile, typically didn’t start until 9:00 p.m. on the East Coast, meaning a much larger audience available to watch the debate. Additionally, while there was some movement between the two debate stages, for the most part it was the case that candidates who got stuck in the undercard debate stayed there, although there were a few notable exceptions in candidates who got promoted or demoted based on the polls. In any case, the main/undercard debate format only lasted until roughly October of 2015 when debate organizers began excluded undercard participants entirely. Not surprisingly, most of those candidates ended up withdrawing from the race before anyone had even voted.

Instead of the main and “undercard” debate, Democrats are going with the idea of two-night debates where the participants would be selected somewhat randomly so that they would include both high-ranked and low-ranked candidates, thus at least theoretically making it less likely that the lower-ranked candidates would essentially be consigned to that status forever due to being included in a debate that nobody was watching. They are also apparently using criteria beyond polling, such as fundraising and other criteria, to determine debate eligibility. These criteria would include how organized candidates were in specific states, although it’s unclear how some of these criteria can be objectively measured.

While this plan is arguably better than the “main” debate and “undercard” idea that the Republicans had, it arguably suffers from some of the same weaknesses. For example, how many people are actually going to watch two nights of debates, especially if the candidates they prefer all end up being in one debate rather than the other? Additionally, it’s unclear if media outlets such as CNN, MSNBC, and the other broadcast networks would be willing to give up two nights of prime-time programming for political debates. Finally, to the extent that debate inclusion will be decided based on non-objective criteria, this could result in some candidates arguing that they are being unfairly excluded or consigned to a second-night event that may not end up drawing as much viewership.

When this idea of multi-night debates was first proposed last year, Jeff Greenfield proposed a completely different idea, no debates at all, at least not in 2019:

The only way to do this fairly is to get rid of all the debates. That’s right: No debates! Let’s cancel political Christmas, at least for all of next year.

There is widespread consensus among Democrats that the party’s 2016 approach—a handful of primary debates, two of which were on weekends—did not work. But in that year, there were only a handful of candidates at the outset. The Republicans, by contrast, had 17 contenders, which forced the party to split debates between “serious” contenders (measured by poll numbers) and a “kiddie table” of lesser entrants, including former and sitting senators (Rick Santorum, Lindsey Graham, Rand Paul) and governors from big states (Rick Perry, George Pataki).

If in fact 25 or 30 Democrats decide to run, the challenge of a rational debate process becomes insurmountable. The DNC, according to the Washington Post, is contemplating going beyond poll numbers—“possibly including staffing, fundraising and number of office locations”—to decide who participates and how. (Historical note: Back in December 2007, perennial is-he-kidding candidate Alan Keyes opened an office in Iowa for the sole purpose of being included in a Republican presidential debate).

But in a field that could include entrants ranging from a former vice president to the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, any process of inclusion will be ludicrous. Perhaps the debates can be segmented by net worth, with a special billionaires’ forum including Michael Bloomberg, Tom Steyer and Howard Schultz. Maybe age could be the measure, with the septuagenarians one night, the Gen Xers another.)

No matter how the field is divided, the prospect of any meaningful exchange of ideas among even seven or eight participants is nonexistent. My memory of the 2016 GOP debates is an endless clamor for the chance to offer a 30-second response to a one-minute answer to a question more or less forgotten by the time the last debater got a chance to speak.

(emphasis mine)

As Greenfeld goes on to note, instead of participating in multi-candidate debates that don’t really accomplish much of anything, candidates would find themselves freed up to participate in different kinds of forums, such as town hall appearances and other processes where candidates have more direct contact with voters than they with journalists. Additionally, such a policy would leave open the possibility of individual networks or other news outlets having their own forums featuring one or more candidates in ways that allow for responses from candidates that last longer than eight minutes. This wouldn’t mean that there wouldn’t be any debates at all. The party can always leave open the option of having such forums as we get closer to the time when voting actually would take place, at which point the field will no doubt winnow down as candidates discover either through a lack of money or a lack of public interest that keeping their campaigns going doesn’t make much sense. At that point, they could use a combination of polling, actual performance in primaries and caucuses that have taken place, and others to determine who participates and who doesn’t. Before that point, though, the kind of multi-candidate affairs that we’ve become familiar with is really just a waste of time so why not give Greenfeld’s idea a try and just say “no” to the idea of early debates? I know I wouldn’t miss them.