Do The Veepstakes Matter? Not Really

The Veepstakes doesn't matter nearly as much as the media tells you it does.

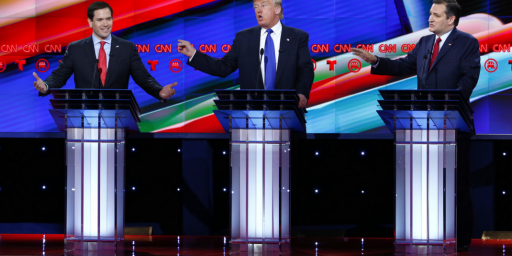

With very little happening in the Presidential race at the moment, we’re seeing more and more attention paid to the question of who may be on Mitt Romney’s “short list” for the Vice-Presidential nomination, and which candidate it might be best for him to select. This week, we saw speculation again turn to Florida Senator Marco Rubio as one report said that Rubio was not being vetted at all, which caused enough consternation on the right that Mitt Romney himself was forced to explicitly say that Rubio was in fact being elected. All of this is occurring, ironically, despite the fact that Rubio himself has said repeatedly that he won’t be the Vice-Presidential nominee. The news about Rubio also say a renewed, and somewhat inexplicable, focus on Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty, who dropped out of the campaign for the GOP nomination last August after a disappointing performance in the Ames, Iowa Straw Poll. Other names mentioned have included Ohio Senator Rob Portman, Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell, and South Dakota Senator John Thune.

To a large degree, the political media is injecting far more drama into all of this than it deserves. Unlike the race for the Republican nomination, there’s really only one person whose vote that matters in this matter, and that’s Mitt Romney’s. Despite that, we’ve seen a number of media organizations polling Republicans about who they’d like to see joining Romney on the ticket and we’ve seen several Presidential race polls that try to measure the impact that various potential VP nominees might have on the race at the state level (not surprisingly, the impact is always fairly minimal even in the potential nominees home state).

None of this is new, of course, the question of VP nominee selection has been the favorite topic of the political media in the period between the end of the primaries and the conventions for decades now. It’s far more intense now, of course, because there’s just so much more media out there, but what we’re seeing today is really just a continuation of the same game the media has been playing since the birth of the modern political media.

The question that nobody really seems to be asking is whether all this attention that the Veepstakes gets is worth it. After all, the Vice-Presidency itself is a relatively powerless institution. Other than breaking ties in the Senate and succeeding the President in the event of incapacity or death, there really isn’t anything for a Vice-President to do unless he’s given tasks by the President himself. The Vice-President technically doesn’t even have the right to sit in on Cabinet meetings, again that’s a courtesy granted by the President. Now, it’s true that in the modern era (at least since Eisenhower-Nixon), the Vice-President’s role has expanded significantly and the relationship between the President and Vice-President has become closer than it used to be historically, but all of that has happened on an informal basis. If a future President decided, for whatever reason, that he or she wanted to freeze their Vice-President out of Administration policy making, there’s nothing that could stop them. That’s the reason that FDR’s first Vice President, former Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, once described the job as “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

Over at The Atlantic, Molly Ball argues that this weeks Rubio kerfuffle proves that the Veepstakes does indeed matter:

You often hear high-minded political pundits declare that the veepstakes doesn’t matter, because in the end, we are assured, running mates rarely decide elections. Can we all declare a moratorium on the trope of pundits deciding what voters do and don’t care about? It’s condescending — who are they to say what voters, the vast majority of whom they have never met, care about? It’s based on a political-science fallacy — just because voters are smart enough to base their final judgments on policy fundamentals rather than relative trivia doesn’t mean they don’t welcome a wide range of information. And the implication that the only things that matter in elections are those that move votes is deadeningly reductive in its capitulation to the horse race above all else — the airy dismissal of interest in political people and stories just because they’re, you know, interesting.

It is also fashionable to declare that this sort of speculation about the veepstakes is pointless and wasteful and serves no apparent interest. But look what we learned from the Rubio affair on Tuesday. We learned, above all, that Mitt Romney isn’t particularly interested in putting Rubio on the ticket with him; that seems, if anything, truer today than it was yesterday: He had to be unwillingly pushed into feigning interest in his party’s favorite running-mate candidate. But we also learend that Rubio has a powerful constituency in the Republican Party that Romney realizes he cannot afford to ignore or alienate; and we learned that Romney, realizing this, is susceptible to pressure. Even with the nomination in hand, Romney apparently remains sensitive to the potential for a backlash from the base. Does that mean it is conceivable that Romney, despite his lofty talk about picking a running mate based solely on that person’s ability to serve and govern and without regard for politics, could be pressured into selecting Rubio for the ticket after all? Meanwhile, if Romney now doesn’t pick Rubio, after having vetted hm, some will logically assume that’s because of something unsavory he discovered in the vetting process — potentially damaging Rubio by deeping the implicit stain on his reputation.

This is why the veepstakes is not merely a parlor game — it’s an interaction between the public, the press, the political chattering class and the candidate. It is a dance whose participants are constantly sizing each other up. The relation of Romney to Rubio changed on Tueday: At the beginning of the day, Rubio was not being considered, and at the end he was, at least officially. Something happened as a result of this public dialogue, and the result could change the outcome of Romney’s choice.

Let’s deal with Ball’s first point right off the bat. While it’s true that we can never know everything that influences every voter in a give Presidential election, and that we cannot run a scientific experiment to determine how an election might have turned out if the identity of a VP nominee were different, what we can do is look at the history of recent Presidential election campaigns. Doing that, we find very little evidence to support the idea that the choice of a running mate has anything other than a temporary impact on the course of a Presidential race. Typically, you’ll find that a candidate will get a minor bump in the polls after a running mate is selected but, since that usually occurs at the same time as the Party Convention, it’s difficult to tell if that bump is due to the running mater, the convention, the fact that the candidate is getting three or four days of relatively positive media coverage, or a combination of all three.

Over the longer term of a Presidential race, though, the most that you’ll see a Vice-Presidential candidate do is rally the base. That’s not an inconsequential contribution, of course, but it also comes with risks because a candidate who rallys the base can also turn of the independent, middle-of-the-road voters a candidate needs to win swing states. This, arguably, what happened in 2008 with John McCain’s selection of Sarah Palin. By the time mid-September 2008 came around, it was clear that while Palin was immensely popular with hardline Republicans, she was incredibly polarizing among independent voters. Given the state of the economy, the unpopularity of the GOP in general, and the incompetent manner in which McCain ran his campaign, it’s not fair to say that Palin lost the election for McCain but there’s no really evidence that she helped him either. Other recent Vice-Presidential candidates, on the other hand, have mostly been a wash when it comes to their impact on the polls, even Dan Quayle who had his own problematic roll-out in 1988. In fact, I’d say that the only recent Vice-Presidential nominee who actually had a substantive impact on the outcome of the race was Lyndon Johnson, and that’s only if you define “recent” as 52 years ago. As Palin, and to some extent Geraldine Ferraro in 1984, shows us, it’s more likely that a VP nominee could harm a ticket than that they could help it. So, Ball’s attempt to discredit the critics of the Veepstakes doesn’t really succeed.

Ball’s second point, that this week’s Rubio kerfuffle taught us something about his importance in the party given his popularity with the base, doesn’t really measure up either. As Daniel Larison points out, there really isn’t anything we supposedly learned from this episode that we didn’t already know:

Romney’s campaign had been telling anyone who would listen that they were inclined to favor boring, experienced politicians for the VP slot, which effectively ruled out Rubio from the beginning. We already knew that Romney is susceptible to pressure. Look at how quickly he dropped his national security spokesman at the first hint of grumbling from a small handful of activists. We can expect Romney to be sensitive to backlash from party activists because he is an egregious panderer with no firm principles. That is something that “we” have known about Romney for at least five years.

We didn’t need the Rubio-vetting episode to know that Rubio has a large constituency in the party. Rubio has less than two years of experience in national office, and he has already been the frequent subject of both presidential and vice-presidential speculation for over a year. Indeed, practically the only reason why the Rubio-vetting episode was newsworthy was that “we” all understood that he was a favorite of movement conservative activists, and so the report that Rubio was not being vetted for a position that many activists thought he should have was bound to be interesting to Rubio’s fans.

Larison is, of course, completely correct here. We really didn’t learn anything about Romney or Rubio this week, and we’re unlikely to learn anything new from any of the media circus that erupts around the question of who Romney’s running mate will be over the next six weeks.

That’s not to say that the selection is entirely unimportant, of course.

When a candidate for President is choosing a running mate, they are really making the first major decision of their campaign and it’s fair to judge that as an example of how their decision making process will work should they be elected President. The candidate is saying, most of all, that the person they are selecting would be qualified to serve in the nation’s highest office should something unfortunate happen to them during the course of the term in office. That’s why John McCain’s selection of Sarah Palin was a problem for so many people. Here was a man of advanced age telling us that someone with a very thin resume that most of us had never heard of before would be qualified to take over for him if necessary. As the election went on and it became clear that Palin’s qualifications were, to put it nicely, questionable many started to wonder what kind of President McCain could possibly be if he’d make such a bad decision the first time he had to do so. So, the reason a Vice-Presidential selection is important is because of what it tells us about the Presidential candidate, not so much because of the identity of the running mate. That’s why you can pretty much ignore all the media speculation over the next two months.

The identity of the veep matters a great deal in very close elections, doesn’t it? Unless we’re willing to say that name recognition, demographics, personality, and such, don’t affect voting, which obviously is not the case.

Would Florida 2000 have come down to 500 votes if Lieberman had not been Gore’s running mate and if Bush had tapped someone with more appeal to moderates and Independents? Seems pretty obvious that if Gore had been running with someone like Tom Vilsack and if Bush had been running with someone like John Engler or Tom Ridge that hanging and pregnant chads would not have mattered so much. What would the 1976 election have looked like if Ford had run with someone like Bill Scranton or someone from Ohio instead of a Kansan?

If Romney taps some 2nd or 3rd-tier veep candidate, and if the election comes down hypothetically to the single state of Ohio, and Obama takes that state by a narrow margin, e.g., 100,000 votes, afterwards could we really say with a straight face that if Rob Portman had been the veep it wouldn’t have mattered? Portman in 2010 won 2.2 million votes. Seems pretty clear that having him on the ticket would have to be worth merely 51,000 net ballots in Ohio to Romney. You could apply the same conceptual logic to McDonnell in VA, Rubio in Fla., Toomey in PA, and either Walker or Ron Johnson in WI.

The way I see it is that the veepstakes is sort of like the NFL draft. It doesn’t really matter. Unless and until it does.

Herman Cain. That’s who Romney will pick, to shore up his support amongst … whatever people thought Herman Cain wasn’t an uninformed doofus that had no business running for president.

I think it’s a lot like watching NASCAR, not too exciting unless there’s an smash-up and a car clips the wall and spins out into the infield.

In recent years Republicans have selected difference makers in the VP slot – Cheney (after the fact, and perhaps the strongest VP in our history) and Palin (whatever Democrats think of her, she electrified base Republicans). Both Clinton and Reagan selected solid Party guys.

Joe Biden, John Edwards, Dan Quayle.

That’s all need be said.

@Jenos Idanian #13:

Joe Biden, John Edwards, Dan Quayle.

… and Spiro Agnew wraps it up.