Fixing the Foreign Service: Effective Forward Deployment

by Dr. Demarche

The Foreign Service has been buzzing this last week in the aftermath of Secretary Rice’s recent speech regarding the administration’s planned focus on what has been termed “transformational diplomacy” (TD hereafter). The Secretary has offered the following explanation as to what this will mean to the world:

I would define the objective of transformational diplomacy this way: To work with our many partners around the world to build and sustain democratic, well-governed states that will respond to the needs of their people — and conduct themselves responsibly in the international system…Transformational diplomacy is rooted in partnership, not paternalism — in doing things with other people, not for them. We seek to use America’s diplomatic power to help foreign citizens to better their own lives, and to build their own nations, and to transform their own futures…Now, to advance transformational diplomacy all around the world, we in the State Department must rise to answer a new historic calling. We must begin to lay new diplomatic foundations to secure a future of freedom for all people. Like the great changes of the past, the new efforts we undertake today will not be completed tomorrow. Transforming the State Department is the work of a generation. But it is urgent work that cannot be deferred. — Secretary Rice, January 18, 2006

The idea of TD as a policy (first floated nearly a year ago with follow up last summer) is in many ways just what the doctor ordered for the Department of State and our diplomats abroad. Just as the military is often accused of preparing to fight the last war, the Department of State has been slow to react to the changes in global power and threats.

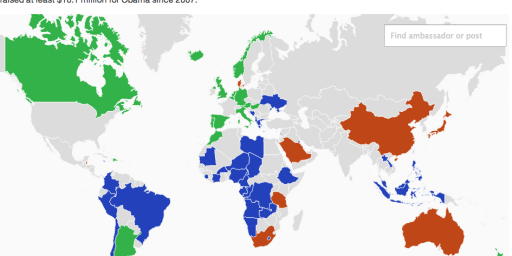

For far too long we have been concentrating our diplomatic efforts on the Cold War battlefields of Europe (and look at what those efforts have wrought). The EU, struggling under its own weight and largely powerless outside its own borders no longer demands out attention as it once did- the goals set after World War Two have been met, the Soviet giant has been slain and it is tome to shift our gaze elsewhere. Never the less, the capitals of Western Europe remain the shining gems in the Foreign Service. Our embassies in London, Paris and Berlin overflowing with senior diplomats while our missions in the places that should matter most to us, the Middle East, South East Asia and the “Stans” ( Pakistan, Kazakhstan, etc) are manned by entry level or junior mid-level officers. The Secretary’s TD plan would begin to rectify that situation, immediately stripping some of the fat from the Euro-zone missions and from Washington (approximately 100 positions) and directing them to where our need is greatest, with many more positions to follow in the future.

The TD plan, detailed here, will also redefine the manner in which our diplomats approach their work. There will be more hands-on work with local governments and a greater emphasis on public diplomacy, and an expanded use of technology to reach out to larger numbers of host country nationals. A greater emphasis will be placed on stabilization of a nation and empowering the people to shape and define their own destiny.

All of these steps are praiseworthy, and all are needed in the current practice of diplomacy, American style. The most striking point in the plan (besides human resource allocation), however, is referred to in the official TD material as Effective Forward Deployment, which is defined as “Diplomats…traveling to their area of responsibility more regularly than ever, using their expertise and experience more effectively abroad.”

This one sentence speaks volumes as to the current state and practice of U.S. diplomacy. The section heading clearly implies, and in large part is correct in doing so, that our diplomatic resources are being used ineffectively. Too many of our diplomats, even in Western Europe, are desk bound, reporting back to Washington on events that are often covered in a more timely manner by CNN and the BBC. Our embassies and consulates are foreboding and inhospitable buildings, security concerns over ride almost every effort to present a welcoming face. Those of us serving abroad have almost no contact with the vast majority of the people who live in our host countries. We are hidden away behind massive walls and locked gates in only the capitals or largest cities, locked in the echo-chamber with the governing elites. I wrote about this last year on The Daily Demarche in response to a 2003 article by Thomas Friedman entitled Where Birds Don’t Fly. Friedman describes the new consulate in Istanbul as lacking only “a moat with alligators and a sign that says: “Attention! You are now approaching a U.S. Consulate. Any sudden movement and you will be shot. All visitors welcome.” Unfortunately this is becoming the norm around the world.

As a result, simply moving positions and declaring that an officer must speak at least two languages and take an occasional posting to a less than ideal post will not solve our problems. We must be able to reach out to the people in the places where we live, and in order to do so we need to rethink the manner in which our diplomats are trained and prepared for each assignment. While there is some mention of FSO training in the TD plan, there is not nearly enough. The Foreign Service needs a concrete training continuum, including language and cultural studies at advanced levels. An entry level officer may be trained in Urdu, for example, and will have to pass a test (graded on a 0-5 scale with 5 being professional translator) to prove that she has reached the minimum level of competency before heading off to post. For most languages that level of competency is a score of 3, although it is often 2 for the “hard languages” such as Urdu. After that, however, the officer is deemed prepared for the rest of her career to work in that language (in theory certain language scores demand a periodic re-test, but if an officer is deemed successful in working in the host language in her annual review no re-test is required).

Why are our officers not expected to improve their language skills while abroad? Why does the minimum skill level required not increase in proportion with responsibility? The sad fact is that many officers actually suffer a decline in language skill while abroad, as they have very little “official” contact with the local population, dealing instead almost exclusively with the local elite who have often studied in the U.S. and speak flawless English. Compound this with the fact that many of our administrative and technical employees overseas, known as Foreign Service Specialists, receive no language training and the problem is even larger. The State Department is adamant that every overseas employee is a diplomat and carries the responsibility for representing the United States abroad. No one seems to have noticed that it is difficult to do so in an effective manner if you cannot communicate with the locals. If every employee abroad is the face of America we should be highly concerned about the perception of arrogance- it is one thing for a tourist from the heartland who has never left the U.S. to assume that speaking slower and louder in English will make the locals understand, quite another for an Embassy employee to do so. Imagine meeting a foreign diplomat in the U.S. who did not speak English, at least at a basic level. What would you think of the country that sent that person abroad?

In an age when world affairs are increasingly shaped by what the policy wonks like to call “non-state actors”- a term which covers everything from Greenpeace to al-Qaeda- our diplomats need the tools and training to effectively deal with the people who comprise these groups. Simply ensuring that a host-country government is not hostile to us is no longer sufficient. Every contact with every host country national, by every American member of every mission abroad, must be an opportunity for that host country national to form a positive image of America and Americans. We should, of course, continue to work with the governments of the world, while at the same time reaching out to the butchers, bakers and candlestick makers they represent. These are the people who have the potential to pilot airplanes into skyscrapers or to bomb shopping malls. Our best and brightest hope is that they are able to form a positive image of us through the Americans they meet in their homeland, and that they share that positive image with their friends and families. We cannot allow something as mundane as the training budget to interfere with this process. The TD plan calls for diplomats to serve as Political Advisors to our military forces- I would argue that by the time our military is involved we have already wasted our best chance to make use of our “diplomatic and regional experience.”

The bottom line is that hearts and minds can only be won with hearts and minds. The Secretary’s plan to shift resources to the areas of the world that are of greatest concern is an admirable one. What happens after those positions are shifted- who fills them, what training they receive and the marching orders they receive will be critical. The Secretary has referred to the time frame for this transformation of the State Department as “generational.” I don’t think it is a coincidence that this is the same idea that bin Laden is said to have expressed as al- Qaeda’s vision of their struggle with the West, I just hope that we have the same resolve as those who seek our destruction.

Dr. Demarche is the pseudonym of a career Foreign Service Officer who until recently was proprietor of The Daily Demarche. His work now appears at American Future.

________

See “Diplomats Will Be Shifted to Hot Spots” for more thoughts on this policy change.

Some questions and some answers…

State has a serious case of “Congressional Terroritis,” that is, mortal dread of Congress. It quakes and quivers at the thought that Congress (or any of its myriad myrmidons) might get cross. Or cut a budget.

State knows that the bad press resulting from dead diplomats would lead to a Congressional inquiry at the least, with the likelihood of the SecState being grilled in camera/on camera most likely.

Thus, it will spend oodles of dollars to build fortress embassies to make sure that we don’t have repeats of the Beirut bombings of the 80s.

Decisions were based on stark calculations: It is better to have live, though less effective diplomats than dead ones who were doing a better job.

Because I worked in Public Diplomacy–whose entire raison d’etre is being in publicly accessible places–a large part of my career was spent fighting the planned closure and relocation of PD offices. They were in impossible locations if security was the driving concern. Usually these offices were downtown, on the main drags, and no way did they have set-backs from the street to mitigate the effects of car bombs.

Of course, this is tension-making. Some people, oddly enough, didn’t feel comfortable knowing that a car bomb outside the front door would take down the entire building. Even those with brass balls were not immune to reality.

While I was in Riyadh, the US Foreign Commercial Service office in Jeddah was located separate from the Consulate in Jeddah. It was very much publicly accessible. It was so easy to get to, in fact, that the Public Affairs Officer in Jeddah tried to get his office relocated there.

I fought against that move, preferring to have him and his staff behind walls. Security forced USFCS to relocate behind walls after the 2003 bombings of residential compounds in Riyadh.

As the attack on the Consulate in Dec. 2004 demonstrated, this was wise. Had USFCS been in their original location, they would have been held hostage if not been killed.

There’s already an imposing wall at State filled with stars of FSOs killed in the line of duty.

It is possible to be out in the public–at least part time–without being stupid about it. But it means being able to get away from the desk. And that’s not always easy.

As in many private sector businesses, State did away with lots of clerical staff in the 80s and 90s. That was good for cutting costs, but rotten for efficient use of highly trained officers. Bare bones Admin and Personnel (sorry, HR!) sections can’t carry the load and much of the work bounces back to the actual line managers of substantive sections.

Other than Ambassadors and some of the security folks, practically no one has American secretaries with security clearances. This means that truly mundane things also get kicked back to the officers–like escorting visitors, collecting and disposing of cable traffic, etc. This is a waste of limited time on the part of trained talent.

My biggest question–and I’d love Dr. Demarche’s thoughts–has to do with recruiting and retaining officers.

I believe I’m of the last generation of “career” officers, i.e., doing 20+ years in the service. Today, you just don’t find spouses–of either sex–willing to work for uncle on an unremunerative basis. For some strange reason, they’re of the opinion that when they work, they should be paid. That’s if they’re willing to give up their careers to go overseas in the first place.

While State no longer rates officers on the behavior of spouses and children, on the willingness of wives to pass the cookies at functions, it still expects an awful lot from unpaid partners of officers.

Maybe State needs to recruit, exclusively, Shaolin monks and nuns, single people willing to put it all on the line without the encumbrance of families. That would solve a major problem, all right.

“Assignment discipline” is necessary, of course. “Worldwide Available” means just that; you can be sent where the service needs to send you, your druthers be damned. State hasn’t been doing much of that for the past 20 years, but it should. (Actually Afghanistan and Iraq are seeing lots of people who never bid on the jobs.)

Hard-to-staff assignments tend to draw officers who can’t get jobs in nicer places. Or officers who are down to their last chance to make something of their careers. Or those who have proved to be such pains in the ass that no one else will take them. This works out nicely for HR, but not so well for the field posts encumbered with problem children.

State also needs to find solutions to other family issues that just aren’t met by typical stateside private sector employees.

While kids are young, they can be dragged around almost anywhere. As they get older, and as schooling becomes more important, then officers correctly start getting concerned about where they’ll be assigned.

I have a smart kid, a really smart kid. He deserved good schools. I did everything within my power to make sure I could get a European assignment when he was in the critical middle grades, and succeeded with an assignment to London. After that, he was willing to go to boarding school for HS, and I could take an assignment in New Delhi, where the American HS wasn’t so great (at least by my standards).

I had absolutely no guilt about getting the London assignment as I’d already done 12 years in hardship/greater hardship posts, and would do another four afterwards.

Were that European assignment not available, I would have walked; my son’s education was that important to me.

My wife got screwed over consistently by State. Prior to our marriage, she was a book editor. My assignments in the Middle East did absolutely nothing for her career as there was very little call for English language book editors in the Arab world. The Arabic training she got was not adequate to editing in Arabic, nor could it have been (ask someone who’s studied Arabic).

While State tried to make jobs available for spouses, they were always jobs that had no future, no career track within State. This has changed somewhat of late, but if a spouse is a professional, there’s little scope for meaningful employment overseas.

So how do you deal with these real problems? It’s not a matter of whimpy demands from spoiled brats. Only one person is getting a salary, is getting all those awards for meritorious or superior performance: the officer. Spouses get a roof over their heads, the pleasure of the officer’s company (mostly). They also get to live in not-so-fun places, dealing with not-so-fun health issues, safety and security issues, learning to shop in various languages, acquiring a taste for those Clorox-strawberries and lettuces. And they don’t get paid for all the fun they’re having.

Try imposing those conditions on the spouses of someone at IBM or Smith-Barney.

While many private companies do send employees–and their families–abroad, it’s not to Tincanistan or Wagamamadoogoo. And those companies offer salaries and benefits packages far beyond what Congress would countenance.

Getting tough is certainly a necessary part of the solution, but it doesn’t do it all.