FEDERAL SALARIES

Daniel Gross makes an interesting point in Friday’s Slate:

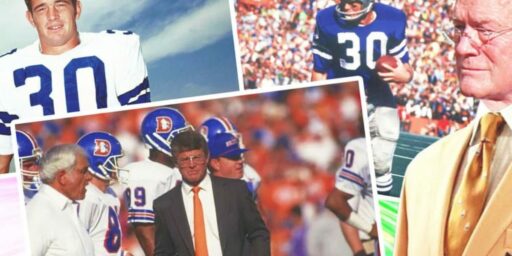

Could it be that the new coach of the U.S. Military Academy is the highest-paid federal worker? Earlier this week, Bobby Ross, the former head coach of the San Diego Chargers, signed on for the largely thankless task of coaching the Black Knights, who just completed a 0-13 season. The 67-year-old Ross cited his connections to the military as a reason for taking the job. The New York Times cited another reason Ross might be willing to sign on to a hapless program that can’t compete for blue-chip players. “Army did not disclose contract details, but his salary is believed to be around $600,000 a year.”

If true, that would mean that the coach of a highly marginal football program at a unit of the Defense Department is earning about 50 percent more than the commander in chief. On his 2002 tax return, Bush listed wages, salaries, and tips of $397,534.

In fact, Ross is not technically an employee of the federal government. According to West Point’s public affairs office, he is an independent contractor to the Army Athletic Association–the entity that handles income from ticket sales and television rights. However, this document on the Web site of the Association of West Point Graduates notes that 35 percent of the AAA’s budget is derived from taxpayer funds. That means taxpayers are only paying $210,000 of Ross’ salary–which would still be more than President Clinton made before the president’s salary was doubled in 2001.

Historically, the highest-paid federal worker has been the highest-ranking official, and the scale of remuneration for public servants has been genteelly low by comparison to the corporate sector. But these days President Bush and Bobby Ross aren’t the only ones making big money while working for a government entity or performing a public service. Look at the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which was established by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2002 after the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation. Chairman William McDonough this year will earn a cool $556,000—about 40 percent more than the president—and the board’s four members will each take home $452,000. Like Ross, McDonough and Co. aren’t technically federal employees, even though they were appointed by the SEC. The PCAOB is a nonprofit company, which pays its salaries with fees paid by the companies it regulates.

Good-government types might be forgiven for being of two minds about the rising salaries. In theory, the ability to earn big bucks while serving the public should have a salutary effect on government, helping to ease the notorious revolving door problem. Many ambitious people view government service as a means of boosting their salaries in related fields: Put in a few years as a low-paid attorney at the SEC, and then you can jump to a high-paying post at a mutual fund company. Wangle a volunteer appointment to the Defense Policy Board, and use it as a platform to gin up lobbying assignments or venture capital investments, as Richard Perle has done. Medicare chief Thomas Scully didn’t even wait until his government stint was over; he was busy negotiating with several different potential employers even as he helped formulate changes in Medicare policy. This dynamic has always been troubling to government watchdogs, who worry that government employees may make decisions that are friendly to the industries they hope to join or return to. Simply paying government workers higher salaries than they could get in the private sector should allay that concern.

But once the big bucks are flowing, let’s not cloak what are clearly career moves in the mantle of sacrificial public service for a noble cause. Yes, all government (and quasi-government) agencies–including the U.S. Military Academy’s athletic department and the PCAOB–have to compete for talent with the private sector. And I can think of hundreds of government-related jobs that deserve to be paid more than they are now–and more than the president earns. But with the nation at war, with the Internal Revenue Service in shambles, and with our economic and fiscal policies in disarray, it seems a little strange that the two areas in which we’re willing to pay top dollar are West Point’s football program and an organization aimed at stopping massive companies from cooking their books. While they may talk a good game, Bobby Ross and the PCAOB grandees are not exactly “giving back.”

Very interesting indeed.

The problem is the comparative: Do soldiers “deserve” more than football coaches? Probably. Ditto school teachers versus, say, NBA basketball players. But we don’t pay people based on the merit of the task they perform, or even based on their level of skill, but rather on the amount of revenue they can generate (in the private sector, especially) and what the market will bear. There are enough PhDs willing to work for $35,000 a year that there’s not much incentive to pay them much more. Ditto, US Presidents and Members of Congress. Frankly, most people would do those jobs for no salary at all; the only rationale for paying presidents and congressmen what we do is that most federal workers are capped based on a percentage of those salaries, and we need to be able to pay federal judges, generals and admirals, and members of the Senior Executive Service reasonably high salaries.

Show me a state where the highest-paid public official isn’t a football or basketball coach. I’m guessing maybe that’s true in a couple of the New England states, but that’s about it. The price of competition in NCAA Division I athletics is high, but would you want our service academies to drop down to Division II or III? Army football, even after a record-setting 0-13 season, has tremendous PR value.

True enough. I think football coaches tend to be paid almost entirely out of athletic funds rather than the state treasury, but salaries of $1 million are no longer uncommon. Indeed, I’d have guessed Ross would have commanded substantially more than $600,000. And I’m betting Army doesn’t even let him do the paid radio gigs and such that most Division-I coaches get.

—