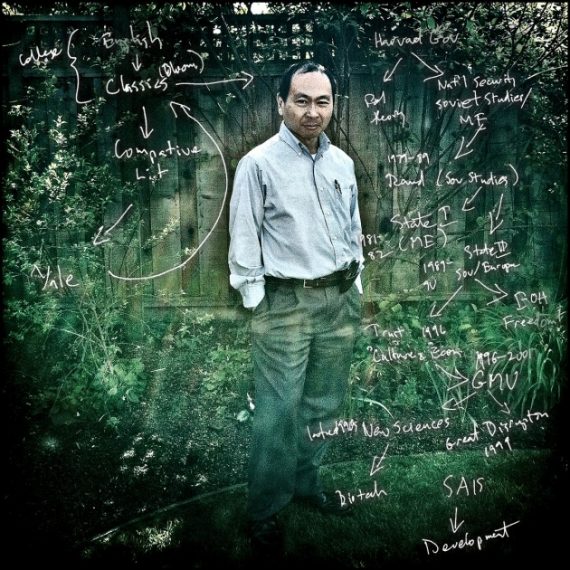

Francis Fukuyama on Origins of Government

Francis Fukuyama: "In the developed world, we take the existence of government so much for granted that we sometimes forget how difficult it was to create."

Francis Fukuyama, who made his name and fortune two decades ago proclaiming The End of History, has been studying the origins of government–and has some predictions about its future.

His new book, The Origins of Political Order, which hits bookstores this week, seeks to understand how human beings transcended tribal affiliations and organized themselves into political societies. “In the developed world, we take the existence of government so much for granted that we sometimes forget how difficult it was to create,” he writes.

Political order begins, he says, in ancient China. By the time of the Chin dynasty in 221 B.C., some 10,000 individual separate chiefdoms across Asia had been corralled into a single state. How did that happen? To boil things down quickly: the state evolved to allow for a more effective making of war. Walking forward through the millennia, he investigates the political evolution of India: the strict social class structure defined its politics. Then the Islamic caliphate: “There is no clearer illustration of the importance of ideas to politics than the emergence of an Arab state under the Prophet Muhammad,” but the spread of Islam “depended also very much on political power” and military slavery. Lastly, he outlines the rise of the Catholic Church in Europe: “The Western separation of church and state has not been a constant since the advent of Christianity but rather something much more episodic—in fact, it established what we know today as the rule of law.”

[…]

What does Fukuyama make of the confounding world of today, with revolutions rocking the Middle East and the rest torn between Washington’s free-market democratic model or Beijing’s authoritarian state capitalism? “There’s something very gratifying about the Middle East demonstrating that Islam is not at odds with the democratic currents that have swept up other parts of the world,” he says. “But what’s most important, actually, is what happens next.” That is, of course, the messy, often contentious process of engineering democracy. These are complicated places—despotic rule has stunted political parties (or, as in Libya, erased them entirely) and gutted civil society. That’s where the real trouble begins. On the “Arab Spring,” he’s bearish. “I guarantee you in a year or two it will not look as hopeful. It’s the whole point of my book. You need institutions, leaders—and corruption has to be under control. These are really the failings of many democracy movements. And it’s happening again—if you look at Egypt, the liberal parties are floundering.”

While the world can’t take its eyes off the Middle East, Fukuyama is, instead, looking ahead to China. Beijing has gone to great lengths—stymieing communications, hitting protests with an iron fist—to keep any democratic wave from rolling too far east. The Chinese government, he argues, will be successful in stifling protest, at least in the near term. “Authoritarianism in China is of a far higher quality than in the Middle East,” he wrote recently. Revolutions, he argues, don’t come from the disenchanted poor, but from an upwardly mobile middle class fed up with anachronistic government that does little but keep them from achieving their potential. So Beijing may be able to keep its people happy for now, but in the coming years its biggest risk is putting off democratic reforms and ending up with a regime that’s fallen behind its people. When the Chinese middle class is no longer willing to forgo political freedom for bigger paychecks, or when the Communist Party grows stagnant, unable to keep up with the masses, then change is going to come, one way or another.

While the provocative title of The End of History has yielded ridicule, Fukuyama’s basic thesis–that there was no ideological challenger to liberal democracy–has thus far proven correct. Radical Islam has been a thorn in our side but the lure of the 7th Century lifestyle isn’t exactly a serious competitor to modernity. Authoritarian capitalism of the Chinese variety has its advantages–and proves that the Western path to economic growth is not the only one–but I agree with Fukuyama that the internal pressures will blow the lid off.

via Blake Hounshell