Funkentelechy vs. the Option Syndrome

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry has coined the phrase “Option Syndrome” to describe the destructive effects of undecipherable legalese on society.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry has coined the phrase “Option Syndrome” to describe the destructive effects of undecipherable legalese on society.

[T]he overwhelming majority of legal documents involve redundant, unnecessary, overwrought, undecipherable legalese.

Just try to read the terms of service to the next website you subscribe to. You’re never quite sure if they’re going to be able to buy your newborn from you.

This is destructive. It increases transaction costs (to an eye-popping extent in the US) for everyone, and also raises real questions of democratic accountability, insofar as the law is supposed to be the expression of the general will, and it is hard for the people to oversee their representatives when the understanding of the laws belongs more and more to a learned elite.

Why “Option Syndrome”?

Because, wherever you look, an option is defined as “the right, but not the obligation,” to buy or sell an asset at a certain date and a certain price. But of course, by definition, if something is a right, then it is not an obligation. Yet you will never see an option defined as a right. Always “the right, but not the obligation.”

I’m not sure the name will catch on since the reference is itself vague to those without specialized training. But there’s little doubt that a system whereby people don’t know what they’re signing and a lawyer is required for even mundane transactions is a bad state of affairs for non-lawyers.

[T]he overwhelming majority of legal documents involve redundant, unnecessary, overwrought, undecipherable legalese.

Oh, brother. Thanks for noticing. Montaigne, writing in the late 1500s:

Why is it that our common language, so easy for any other use, becomes obscure and unintelligible in contacts and wills, and that a man who expresses himself so clearly, whatever he says or writes, finds in this field no way of speaking his mind that does not fall into doubt and contradiction?…

Our French laws, by their irregularity and lack of form, rather lend a hand to the disorder and corruption that is seen in their administration and execution. Their commands are so confused and inconsistent that there is some excuse for both disobedience and faulty interpretation, administration, and observance.

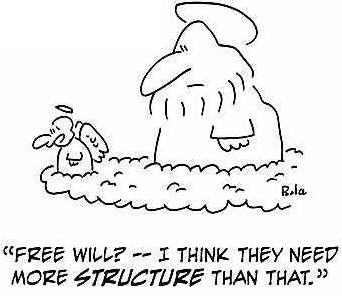

… Fantasies about “clear laws” and “legalese” derive from a childish view of the law. Laws are not handed down by wise daddy-figures. They are negotiated by competing powers each of which is trying to get a leg up on the others. Everyone wants to get ahead.

In short, the confusing, complex nature of legal language is a *feature* of a free-market democracy in which capitalists and consumers, lobbyists and interest groups, compete with one another.

One in which the lobbyists and interest groups typically win.

One in which the lobbyists and interest groups typically win.

This misses the point. Lobbyists and interest groups “win” because their opponents are *other* lobbyists and interest groups.

It’s not “special interests vs. The People.” People who really want certain laws enacted or amended, form or join special interest groups. Or, if those “people” are corporations, hire lobbyists directly.

If we want philosopher-kings to hand down disinterested legislation, then we’re in the wrong country, under the wrong Constitution.

(Tho I gotta tell ya, I’m a philosophy B.A., and from what I’ve read, you really, really do not want the philosophers writing the laws. Particularly the German Idealist philosophers.)

There is only one problem with this, in a democracy the minority group is often ignored and at worst trampled. The median voters when preferences are singled peaked is the deciding voter, and by definition is not part of the minority.

Thus to make it sound like it is a “free market” is a nice rhetorical slight of hand, but once you involve the government the “free” part becomes problematic.

This is a naive and shallow view and ignores things like transactions costs to forming special interest groups and funding lobbying organizations. The free rider problem is the most obvious problem. The other is apathy. Suppose an industry wants to pass a law that will raise the price of the good they produce by $0.1, but have neglible impact on their production costs. This might not register on 99.99% of voters “radars” and the 0.01% that do notice are maybe too small a group to effect much change.

Mancur Olson looked into this with his seminal work The Logic of Collective Action.

It is the same reasoning that undercuts collusion in a perfectly competitive market. Collusion there is usually considered extremely difficutl if not impossible. Why? Suppose you are one of the firms and that all other firms produce at the collusive level of output, but you don’t. Prices still go up pretty close to the monopoly price, but you will reap much larger profits than the other firms because your level of production is so much higher. This calculus is true for all firms, so collusion becomes very problematic.

So how do you get collusion? A small number of firms and/or a coercive mechanism to enforce collusion. Look at OPEC; for years that enforcement mechanism has been Saudi Arabia with its massive reserves. They could credibly threaten to push oil prices extremely low if production quotas were at least somewhat adhered too.

The idea that we have a “free” market place in regards to politics and policy is a nice fantasy, but it is just that a fantasy. It is in fact a market place where competition is imperfect and the advantage are towards those with the strongest incentives and the most money at state…which usually are self-reinforcing.

Nice try Anderson, but you really took away the wrong message from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Blame litigation. If the language is always “the right, but not the obligation,” you can bet that it’s the result of someone suing over a document that simply specified “the right.” Did they win? That’s irrelevant. What matters is that both sides had to pay lawyers after the fact to fight over the meaning of the document, and this increases transaction costs MUCH more than does a bit of legalese on the front end.

While most people don’t speak the way documents are drafted, there are very good reasons that they are drafted a certain way. Legalese is designed to be precise, not easy to read. Are there redundancies? Certainly. However, unless you’ve had to pay $100,000 in fees to litigate the meaning of your (easy-to-read) agreement, you’re better off sticking with precision over simplicity.

Has there ever been a truly free market in the real world or do they only live in economics texts?

It seems that these things like collusion that don’t happen in the theoretical construct of a free market are everywhere and always rampant.

Grewgills,

With a free market you or I can always opt to not participate. Kind of hard to “opt out” with government. They have these things called, guns and police officers and spiffy coercive powers that they can use to keep you from “opting out”.

I would have thought this difference was rather obvious.

Collusion absent some sort of enforcement mechanism is difficult, one source of an enforcement mechanism is the State.

system whereby people don’t know what they’re signing and a lawyer is required for even mundane transactions is a bad state of affairs for non-lawyers

You say that like it’s a bad thing.

ouch. A lot wrong here.

First of all, the only role of government in most contracts is to enforce the terms of it, through the judiciary. The guys with guns only get involved if one side or the other decides to ignore the court.

Second, most contracts impose both rights and obligations on both sides. The distinguishing characteristic of the “option” is that the optionor can call the asset, but the optionee cannot put it.

Can one think of a contract in which a party would have both the right and the obligation to purchase an asset at a point in the future? Sure; they’re called “futures”. If the seller fails to perform, the purchaser can go to court and force the sale. But if the purchaser fails to perform, the seller has the right (and the purchaser has the matching obligation) to go to court and force the purchaser to buy.

If one describes an option only by discussing the right of the purchaser, then you’ve been silent on the powers, if any, of the seller. Now, one could assume that silence equals a lack of power, but one could also assume that the person describing the option doesn’t know what he’s talking about.