House Moves to End Public Financing of Presidential Campaigns

The House has voted to repeal the broken system of financing presidential elections.

I am basically a free speech absolutist, especially when it comes to political speech. Further, I am persuaded by the argument that money is speech insofar as the only way to get speech into the public square is via the spending of money. These proposition lead to a conclusion that regulation of spending on campaigning or on interest oriented ads is therefore problematic, if not constitutionally impossible.* Further, the protections of the First Amendment lead to a grand difficulty (if not an impossibility) is fully regulating the way in which a campaign season functions (something that is possible in the British context, for example).**

I am basically a free speech absolutist, especially when it comes to political speech. Further, I am persuaded by the argument that money is speech insofar as the only way to get speech into the public square is via the spending of money. These proposition lead to a conclusion that regulation of spending on campaigning or on interest oriented ads is therefore problematic, if not constitutionally impossible.* Further, the protections of the First Amendment lead to a grand difficulty (if not an impossibility) is fully regulating the way in which a campaign season functions (something that is possible in the British context, for example).**

Having said all of that, I am not unsympathetic to the logic of public financing arguments in the sense that it would be nice if we could focus solely on what politicians have to say and what they do rather than having the deal with her question of who is paying for what, not to mention that incumbents have massive advantages when it comes to fundraising.*** Further, regardless of one’s views on the subject, one has to admit that the amount of time that politicians have to spend fundraising is a problem and, moreover, that the relationships between big donors/fundraisers and politicians is not in the spirit of democratic governance.

Still, the practicalities of creating a public financing system in the US (setting aside, for the sake of discussion at the moment, of cost) makes me wonder as to whether it even ought to be pursued. Specifically, if independent actors can spend whatever they like, then there is an undercutting of whatever benefits might exist in a system of candidate financing that is level, public and self-contained.

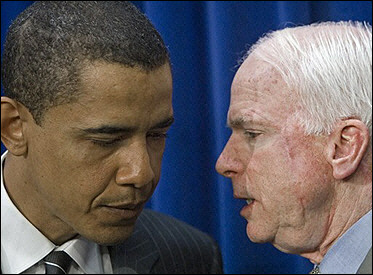

This is relevant to the design of the system we currently have in place to fund presidential campaigns, as it theoretically provides a self-contained process for the general election, where the major party candidate receive a lump sum and therefore spending capacity is theoretically equal between the candidates. Likewise, there is a partial public financing provision for the primary phase of the process. However, if there are piles of private cash waiting to be spend in parallel fashion to the public monies, it not only undercuts the alleged field-leveling element of the public monies but also begs the question of why a candidate wouldn’t simply eschew the public money (and the strings attached thereto) and simply target the private money alone. And, of course, George W. Bush did exactly that in the 2000 primaries (a tactic followed by other candidates in 2004 and 2008) and Barack Obama did so in the general election in 2008.

In short: the basic system that was created by the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (as amended in 1974) has all but totally collapsed. Further, as I tried to outline above, the goals of the process (such as lessening the need for candidates to raise funds and to level, to some degree, the playing field, financially speaking) never worked due to, amongst other things, the confluence of the First Amendment and mountains of private cash being spent exercising the rights found therein.

All of this is to say, I have no problem with the House trying to repeal the current system of partial public financing of presidential campaigns. As Bloomberg reports: U.S. House Votes to End Campaign Finance System, Senate Unlikely to Agree

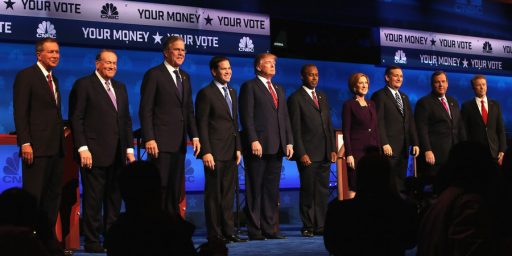

Legislation passed yesterday by a largely party-line vote of 239-160 would abolish the funding system almost four decades after the Watergate scandal that led to its adoption. Republicans cited the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office’s findings that their action would save $617 million over 10 years.

While being billed as savings (and it is a savings, albeit a rather minor one), it strikes me as ultimately an admission that the current system simply doesn’t work properly.

Of course, as noted, it is rather unlikely that the Senate will acquiesce to the killing of the program.

*Although I favor total disclosure, something we currently do not have.

**A major problem here is not just the question of whether independent actors can find a way to campaign directly for a candidate or party, but the simply fact that there are ways to campaign without mentioning candidates at all. Such actions cannot be curtailed under the First Amendment. As such, the fundamental ecosystem of a campaign season is really out of the control of regulators in our system. Now, in the UK, for example, there are strictures on the length of campaigns and the use of TV in the process. This is possible because there is no First Amendment (or similar provision) in British law.

***And I fully acknowledge that having the most money does not guarantee victory, as President Perot and Forbes would, no doubt, testify. Still, it is impossible to state that money doesn’t matter or, more to the point, that if one had to choose running for office with the most money or the least. that one would readily choose the former over the latter.

The idea that money is speech and therefore cannot be limited, but at the same time favoring a disclosure requirement, is basically saying that anonymity in speech shouldn’t be protected. Do you agree with that assertion? I personally don’t see how the goal of free speech can be accomplished without allowing it to be done anonymously when desired. Our country was practically founded on anonymous or pseudonymous speech.

Michael, if money is exactly speech you’re right.

But then again, the IRS thinks they have right to all kinds of “anonymous” spending.

@Michael:

I think that in terms of campaign spending that there is overriding public interest in knowing who is paying for it. You want to write an anonymous blog or newspaper column, more power to you. You want to bankroll an advertising campaign, then I think you need to disclose.

@Steven Taylor:

Do you think the New York Times could be required to disclose the names of people who’s columns they publish when they are advocating for or against a candidate? How about smaller presses? When they start to blur the lines between op-ed and advertisement, should the FEC step in and demand a name?

@Michael:

No, I don’t. (Although, I would point out: you do know who funds the NYT).

There is a difference between political advocacy in the press and paid political advertisement.

Indeed, we already have any number of regulations on advertisement that do not apply to the press. This is not all a radical notion.

I find this argument about anonymous funding of attack newspapers in the 1790s means that it is anathema to ask for those who bankroll political campaigns now to disclose who they are to be problematic.

Perhaps I should clarify, as per JP above, that I don’t mean that money is literally speech, and therefore something you cannot regulate. The spending of money can be regulated, it is simply the content of the speech that cannot be regulated.