In Defense Of The Electoral College

The Electoral College is the worst way to elect a President, except for all the others.

As both James Joyner and Steven Taylor noted earlier this week, Massachusetts became the latest state to sign on to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, a proposed agreement between states that would, effectively, bypass the Electoral College in Presidential Elections:

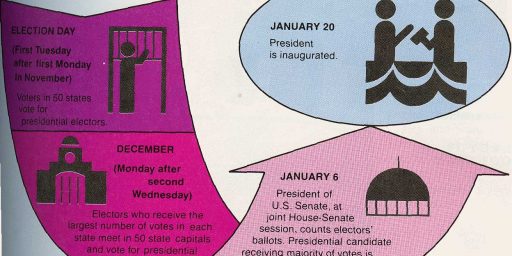

Under the U.S. Constitution, the states have exclusive and plenary (complete) power to allocate their electoral votes, and may change their state laws concerning the awarding of their electoral votes at any time. Under the National Popular Vote bill, all of the state’s electoral votes would be awarded to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The bill would take effect only when enacted, in identical form, by states possessing a majority of the electoral votes—that is, enough electoral votes to elect a President (270 of 538).

So far, only five states totaling 55 Electoral votes have passed NPV bills. If the Massachusetts bill becomes law, that would make it six states totaling 67 Electoral Votes, 203 votes short of the majority. So, we’re not looking at something that is likely to go into effect any time soon.

Moreover, there appears to be a fairly good argument that the NPV would be unconstitutional if it ever went into effect. While it’s true that the Constitution largely leaves up to the individual states how Electors are chosen, Article I, Section Ten clearly prohibits states from entering into inter-state compacts without the approval of Congress:

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

The National Popular Vote “compact”, therefore, would clearly be unconstitutional unless it also received the approval of Congress, which seems unlikely.

But the fact that something is unconstitutional doesn’t stop some people. For example, writing about the proposal in the Washington Post about three years ago, E.J. Dionne made this rather astonishing comment:

Yes, this is an effort to circumvent the cumbersome process of amending the Constitution. That’s the only practical way of moving toward a more democratic system. Because three-quarters of the states have to approve an amendment to the Constitution, only 13 sparsely populated states — overrepresented in the electoral college — could block popular election.

So, basically, the NPV is a blatant end run around the Constitution because, well, it’s too hard to amend the Constitution. As I noted a few weeks ago, that’s sort of the idea behind Article V.

Nonetheless, the NPV represents only the latest attack on the Electoral College, which is commonly denounced as an undemocratic relic of the past. As Rick Moran notes, though, there are arguments in favor of keeping the Electoral College that far outweigh the arguments against it:

The original intent of the College was to keep the decision for president entirely out of the hands of citizens and place it in the hands of “wise men” who would presumably act in the national interest in choosing a president rather than base the choice on the selfish interests of the rabble. The Electoral College was amended in 1804 to reflect the emergence of political parties, and states mostly settled on a “winner take all” formula for choosing electors.

This boosted the influence of states in national elections by forcing candidates to run campaigns that reflected the federal nature of our republic. The early divisions of big state vs. small state in the country were augmented by urban vs. rural, west vs. east, north vs. south, and agriculture vs. manufacturing divisions to which a candidate for president had to address if he were to be successful.

The magic formula to reach a majority of the electoral college votes, therefore, was a test of the broadest possible appeal of a candidate. It guaranteed that no region, no interest would be slighted by a candidate who did so at the risk of alienating key groups and losing precious Electoral College votes in the process. Rural voters from north and south, urban voters from the coast and the interior, were lumped together and specific appeals were tailored to win them over.

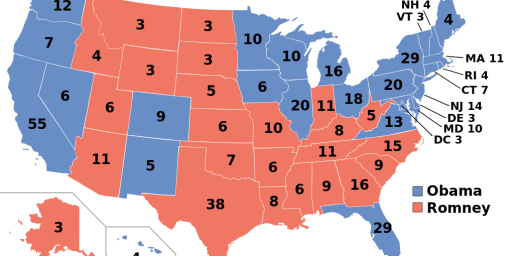

The other major reason to maintain the Electoral College is that it confirms the federal nature of the United States government. It is not surprising that the impetus for the Compact is coming from heavily Democratic states. Direct election of a president would place a premium on wholesale politics. In the 2008 election, Barack Obama took 9 of the 10 largest states, running up huge majorities in the popular vote in states like California, Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, and Michigan. In a race decided by the popular vote, the Republican would be at a distinct disadvantage in that he would be forced to run a defensive campaign, trying to cut into the Democrats huge advantage in coastal and heavily urbanized areas while defending turf in far less populous regions. The disparity would mean that the Republican would spend far more per vote than the Democrat.

That, in essence is the biggest argument against getting rid of the Electoral College. Without it, Presidential candidates would concentrate their resources even more in the areas where the votes are, ignoring the vast middle of the country. That’s exactly what the Founders were trying to prevent when they set the current system up; the Presidency was supposed to be an office that represents the entire country, not just it’s population centers. Eliminating the Electoral College would leave small states at the mercy of large ones even more than they are now.

Instead of eliminating the Electoral College, it would be far preferable to reform it by adopting the District Method:

This method divides electoral votes by district, allocating one vote to each district and using the remaining two as a bonus for the statewide popular vote winner. This method of distribution has been used in Maine since 1972 and Nebraska since 1996.

This resulted in Barack Obama winning a single Electoral Vote in Nebraska in 2008 as a result of his win in the state’s Second Congressional District.

The District Method has many advantages over both our current system and the NPV.

First of all, it maintains the Electoral College’s purpose of balancing large states against small ones, and regions against regions while at the same time addressing one of the biggest criticisms of the way that we elect Presidents. By tying at least one electoral vote in each state to a Congressional District, the proposal would put nearly every state into play in a Presidential election. Yes, the proposal would benefit Republicans in California, but it would also benefit Democrats in states like Florida and Texas. In the end, the benefits would probably balance themselves out across the nation, and candidates would be forced to run a campaign that addresses the country as a whole, rather than one that merely focuses on a few big states.

Second, unlike the NPV, the Congressional district allocation method has been tried before, and works. Both Nebraska and Maine have had this system in effect for several years and it’s worked just fine.

Finally, unlike the NPV, the Congressional district allocation method is completely constitutional.

If the District Method had been in place in 2008, Barack Obama would have won with 301 Electoral Votes to John McCain’s 237. Still a victory for Obama, but a much closer reflection of how close the race actually was.

And what if the District Method had been in place in 2000 ?

Well here’s how I think it would’ve turned out:

- Bush won 228 Congressional District, while Al Gore won 207 (Source here), so we start out at Bush 228 Gore 207.

- Bush also won 30 states (if you include Florida) to Gore’s 20 + D.C., (Source here)which would give Bush an additional 60 Electoral Votes to Gore’s additional 43.

Thus, that would have given Bush a total of 288 Electoral Votes to Gore’s 250. Even if you did give Florida to Gore, assuming no shift in the district allocation, the total would have been Bush 286 Gore 252. There would have been no hanging chads, no Constitutional crisis, no Bush v. Gore.

Sounds like another reason we should consider adopting this nationwide.

As you know, Doug, I’m a HUGE fan of the District Method, but we need to be careful with those counterfactual “How would past elections have turned out…” analyses — just as we must remember that “Gore won the popular vote..” is the worthless screech of idiots.

Candidates wage electoral campaigns, not popular campaigns or even District Method campaigns. We can never know how things “would have turned out” because the inputs would have been different.

But yeah, District Method FTW!

There’s a tendency to see the Framers too much as political visionaries and too little as politicians representing constituencies. The Senate and the Electoral College exist, not so much out of any theory of balancing of power but out of the political vagaries of 1787.

The Constitutional Convention was supposed to be about reforming the Articles of Confederation but they realized the whole thing had to be scrapped. Still, the representatives of the small states had a fallback position: They were equal to the large states under the Articles, which operated on the precepts that the 13 states were sovereign entities uniting only for defense and international trade. So, we got the Connecticut Compromise and other measures that gave the small states less power than they had but more power than they ought under a system of popular sovereignty.

Over time, the compromise actually became rather absurd. The difference between the largest and smallest states now is geometrically larger than it was in 1787. But we’re stuck with the arrangement because the system was intentionally designed to make massive institutional changes difficult.

“…the biggest argument against getting rid of the Electoral College. Without it, Presidential candidates would concentrate their resources even more in the areas where the votes are, ignoring the vast middle of the country.”

I guess it depends on what your core principles are. If you believe in the primacy of the concept of “one person, one vote” – the political equality of all citizens – then the spectre of politicians concentrating resources “where the votes are” is not so troubling.

If, on the other hand, you respect other principles – some abstract notions of fairness that are not tied directly to equal representation – such as giving an extra boost to the voices of rural voters – then I guess you would be attracted to some of these “affirmative action”-like schemes such as the Electoral College.

Doug,

I’ve made this argument before and James has slapped it down. The states have made these compacts before without getting congressional approval and there doesn’t seem to be any case law saying one way or the other, according to James. I’m too lazy to check FindLaw myself, but I don’t recall hearing about Congress approving compacts for water rights or anything else.

Doug,

I need to (and have been meaning to) write something about this this, but two quick thoughts that are key:

1) Moran is wrong is his assessment of the 12th Amendment–I will post something on that in a minute (started to do so here, but it was going to be too long).

2) The basic logic about Reps and Dems and concentration of votes is simply incorrect. You are applying electoral college logic (i.e., where voters are locked into geographic locales and cannot be freed on election day if their state goes the other direction) to a system in which the boundaries would no longer matter. Yes, a Dem would still be more likely to win the majority of votes in the CA, but a Republican would also get votes from CA. It would utterly change the dynamic of campaigning. All votes would equal.

Dems in TX would matter and Reps in NY would matter–in ways they currently do not.

Indeed, you write the following about the district method: “In the end, the benefits would probably balance themselves out across the nation, and candidates would be forced to run a campaign that addresses the country as a whole, rather than one that merely focuses on a few big states.”

But that is especially true about a true national vote (indeed, it is one of the best arguments for a true national vote). Indeed, the district method (which I would prefer to the current system, yes) still maintains a a lot of the problems with the current system–especially with the fact that so many districts are gerrymandered. Indeed, one could sit down and determine which districts are blue, which are red, and which are swing in just the same way as do now with states. This really isn’t as radical an improvement as one might think at first blush.

As to the popular vote initiative, and its Constitutional problems – “No State shall,… enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State,” – I wonder – is there some large body of Constitutional jurisprudence that defines exactly what this means? Because it seems to me that states are forging agreements amongst themselves all the time – to address regional issues, on matters of reciprocity for licenses, or all manner of other issues etc. I doubt that all of these must be signed off on by the Congress…

Two more quick thoughts:

1) While I reluctantly support NPV, my guess is that it will not happen, making much of the conversation about it moot.

2) James hits the nail on the head. The bottom line with the EC is that of the various institutional innovations created in 1787, it is one of the clunkiest and it never even worked as intended. We (and I have done it myself in past) have a tendency to try to retrofit all of these ideas as having a grand purpose. The EC was one of the last things done at the convention and was a shift away from simply having Congress select the President outright–although under the EC the House was still supposed to select the president with the states basically providing nominations via their electoral votes.

@Tano,

No, there isn’t a large body of law on the interstate compact issue. If NPV were challenged in Court, it would be largely a case of first impression.

@Steven,

I hear what you’re saying, and I’m not sure that the DM would be a cure-all, but given the choice between NPV, the District Method, and the status quo, I would consider the DM to be the best of all possible options. Since I am not a majoritarian, I don’t have the same objections to the Electoral College that others have.

Robert,

The SCOTUS does not appear to have ever struck down a compact for want of Congressional approval, but it has suggested in cases like U.S. Steel v. Multistate Tax Comm’n, that it would strike down a political compact that would change the relationship between the national government and the states, or between the states themselves. Since advocates of the compact describe it as an end run around the Constitution, I would think this compact would be ruled unconstitutional or the compact clause is meaningless.

(Most multi-state compacts do obtain Congressional approval since states don’t want to risk non-enforceability issues and most are relatively uncontroversial to non-compact states)

I would favor the district method if I lived in a state in which the districts are not gerrymandered to produce outcomes. Where I live, I would say my vote counts more on a state-wide winner-take-all method.

@Doug:

I am sincerely curious as to your non-majoritarian defense in terms of electing presidents. Depending on what you mean, I am sympathetic to the general notion that not all things in government, even in democracies, ought be decided from a majoritarian position. However, I am not sure what the argument would be in this context.

S

“the Presidency was supposed to be an office that represents the entire country, not just it’s population centers”

You seem to believe that the nation is something other than it’s people.

“Eliminating the Electoral College would leave small states at the mercy of large ones even more than they are now.”

Under the current system, the small states have disproportionate influence on national politics. Is there some reason why this is preferable to the reverse? There would still be government largess, but instead of subsidizing Corn Syrup and Bridges to Nowhere, we would be subsidizing bullet trains linking the major cities. Is that really such a bad result?

Wouldn’t the nation actually be better off focusing its resources on its economic centers, rather than (for example) sending Federal funds to Alaska to fight terrorism? And by definition, the population centers <b>are</b> the economic centers.

Well, that’s basically where I’m coming from. The Constitution contains a number of limits on majority power — the Electoral College is one, the Senate is another — because the Founders were suspicious of majority power in general. One could even call the Bill of Rights an anti-majoritarian document.

You’ve raised some interesting arguments in your response post, I look forward to reading more and I’ll probably have a response back at some point.

“One could even call the Bill of Rights an anti-majoritarian document.”

Seems to me that there is a huge difference between the “anti-majoritarian’ aspects of the Bill of Rights – in which the minority is protected from a potential tyranny of the majority by establishing limits to the scope of power that the (majority-controlled) government can wield – and the “anti-majoritarian” aspects of the Electoral College – which can bestow power on a candidate who is supported by a minority of voters.

Nobody has hit on the most serious change, that the office of the President is currently a federal position, where as the NPV would turn it into a national position.

“”I guess it depends on what your core principles are. If you believe in the primacy of the concept of “one person, one vote” – the political equality of all citizens – then the spectre of politicians concentrating resources “where the votes are” is not so troubling.””

“”””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””

Tano;

The primacy of the concept of “one person, one vote” would seem to produce the political equality of all citizens, at least and perhaps only in the polling booth.

It concerns me that the real world result would be a huge imposition on both the citizens of smaller states, and on the soveriegnty of the states themselves.

The citizen’s of smaller states prosperity it appears would become chattel to the bully states which could dictate a whole new onerous system of laws aimed at supporting these newly created centers of increased power.

I see this as not substantially different from , the lynch mob and the victim adhering to the “one person, one vote” principle.

While the principle above makes a very convincing soundbite, it tears at the seams of the union .

The question remains, why does no substantially populous state proportion their EC votes?

Nobody has hit on the most serious change, that the office of the President is currently a federal position, where as the NPV would turn it into a national position.

This strikes me as saying that if an object is round it is a circle. It other words, in this case it is a distinction without a difference.

“The question remains, why does no substantially populous state proportion their EC votes?”

I have a better question for you. Why does no other jurisdiction find it necessary to enact an Electoral-College-like system to protect the interests of minority groups?

Consider California, or Texas. Huge states, with populations and economies bigger than most of the countries on this planet. As large and diverse (racially, sociologically etc etc) as America itself a century or so ago. Has anyone ever perceived a necessity to elect the Governors of these states by some sort of an Electoral College – so that the smaller, less populated counties did not suffer some horrible fate that you imagine the small states would suffer on a federal level without the EC?

I never heard of such a thing. I don’t see any evidence that the bad things you imagine would come to pass. Where has such things happened?

@Doug:

I wholly concur about the BoR, and indeed that was one of the things I was thinking about when I noted that I hold certain anti-majoritarian beliefs. I will leave the Senate debate for another time. However, in regards to selecting a singular office holder, I am unclear on how an anti-majoritarian philosophy makes sense–surely if the citizens have to choose 1 person to occupy 1 office, majority rule of some sort ought to apply.

Otherwise you are saying that the minority (even if it is a bare one) ought to have enhanced powers in such a selection. I see no justification for that.

@Floyd:

Why would allowing each citizen’s vote to count the same lead to any of the above? What’s the evidence? And what “newly created centers of increased power” are you talking about? One person, one vote?

Tano;

You’ve brought up just the point that I had made earlier, which was the reduction of the states status to that of counties. Thanks for that, Steve Taylor thinks otherwise.

I’m sorry but I won’t address a question which was in direct response to a direct question. It may well be a “better question” even with some merit,but it is a poor answer.

As for examples, there are already abuses of smaller states soveriegnty, such as the cases of Utah & Nevada’s constant struggles. I’m sure there are better examples but I haven’t dwellt on the subject. I think this move would exaserbate the issue.

To once again use your “counties” analogy… Intrastate politics foreshadow this abuse in microcosm… Chicago for example is the tail which wags the dog called Illinois, by using “downstate” tax payers with contempt as a source of revenue without the return of any consideration.

The largest states are already obscene centers of largess, seeking a way to sate their insatiable appetites for spending, and salivating across state lines for helpless victims.

Fish are fish, but it’s the big ones who most often feast on the small.

Steve’s [and I presume your] simplistic and persuasive “soundbite” [one person , one vote] presumes that a person is a citizen of United States , but only a resident of any particular state. This is a commonly held opinion , but one with which millions have taken issue over the years , sometimes with dire consequences.

It may well be the key to understanding why we will likely continue to differ on the issue.

One point of “opti/pessimism”… I’m guessing that we will see an inexorable slide in favor of your argument, since the simplicity of “one person,one vote”outpersuades the true complexity of the issue.

“I’m guessing that we will see an inexorable slide in favor of your argument, since the simplicity of “one person,one vote”outpersuades the true complexity of the issue.”

Yes, I agree with that. It has a powerful simplicity that cuts through the obfuscating complexities behind which privilege hides. “One person, one vote” is, I think, one of the absolute core principles of American democracy – a goal toward which we have moved relentlessly since being propelled on this trajectory by TJ’s phrase – “all men are created equal”. That meant, of course, political equality, and an equal voice at the polls is the obvious manifestation of that principle.

@JJ

“There’s a tendency to see the Framers too much as political visionaries and too little as politicians representing constituencies.”

Yeah. I wonder what The Founders would say about the hyperveneration they’re held in in some quarters. Something like this, I’d bet:

We came up with something good, not something perfect. What would you expect, really, of imperfect men?

If the EC is so good why bother changing it at all?

District counting would be subject to state’s assemblies-resulting in situations such as 90% minority districts voters been essentially disenfranchised.

Why should voters in smaller states get a greater say than other individual voters?

Your proposal pushes the current problem one level down- candidates would still not campaign in a majority of the districts.

You missed the only advantage of EC- elimination of fringe candidates.

@Floyd:

You are going to have to explain the above again, because I honestly have no idea what you are trying to say.

I will say this: historically speaking the people who have taken issue with one man, one vote, were typically people who didn’t want to share the franchise (i.e., the right to vote) with others such as blacks and women.

If it helps in terms of understanding my position, then yes: only citizens can vote.

I think that the best argument for the electoral college is that it discourages vote fraud in the presidential race. Consider the places where it would be easiest to get away with voting fraud: political jursidiction where one party is dominant over the other. It is easier for Democrats to get away with things in Massachusettes and easier for Republicans to get away with things in Utah. Thanks to the electoral college, though, they derive no benefit from doing so. Utah gets five and Massachusettes gets 12 electoral votes no matter how many extra voters the parties can produce in those states. The only place where a party can benefit from fraud is in a state where the two parties are nearly equal and the fraud can flip the state from one party to the other. And that is precisely the place it’s hardest to get away with it, since the other party is just as powerful and able to prevent it.

If we switch to a popular vote system, however, every extra vote in Utah and Massachusettes helps shift the national balance. Under this sytem elections will invariably degrade into ballot stuffing competitions between the most partisan states in the country.

@Story:

Upon what do you base that argument save surmise?

@floyd

“The largest states are already obscene centers of largess, seeking a way to sate their insatiable appetites for spending, and salivating across state lines for helpless victims.

Fish are fish, but it’s the big ones who most often feast on the small.”

Oh, give it a rest. The “small” states get by on the tax largess of the “big” states:

http://scatter.wordpress.com/2009/02/16/red-state-blue-state-welfare-state-subsidizing-state/

Steve;

Let’s just say that the debate rests on whether one believes in state’s rights, which truly is the crux of the issue.

I will try to be even more direct and unambiguous in the future, even at the risk of being simplistic.[lol]

Your position has been clear from the start, no clarification needed.

I could, however, infer from your writing that you believe that one typically must be a racist [or a sexist] to disagree with you on this issue. Can I assume that was not your intent?

Tangent…

as for “only citizens can vote”…wish it were true. Perhaps it should read…”Only citizens should vote.”

Tano,

You have touched on what is truly a sad commentary on the American electorate of late….. All complexity is ubfuscation, so no issue is fleshed out enough to affect the formation of opinions, even though great “soundbites” often only facilitate the swallowing of camels without even the benefit of mastication.

BTW, I must apologize for the obvious slip, which you have done well in taking advantage… In the quoted sentence I meant to use the word “simplistic”….

I contend that….One person, one vote is a simple principle being used here in a simplistic manner.

While similar, there is an unspanable chasm between the two words in this context,

my bad.

@Floyd:

I would politely ask how you are inferring such. To point out that past opposition to “one man, one vote” has been in the context of race and gender is historically accurate. I am accusing you of nothing. As noted above, I am unclear as to your point in the above-quoted response.

I find, by the way, the general notion that states trump the individual citizen to ultimately be problematic and begs the question as to whom it is that the states are supposed to serve in first place.

1] A simple “no” reply would suffice for the first response.

I said “I could” and asked if that were the case.

2] I agree, in general, with your second statement. however to reiterate…” Let’s just say that the debate rests on whether one believes in state’s rights, which truly is the crux of the issue.” “States Rights” means the rights of the citizens of those individual states.

You and I both know we have come to an impasse, and certainly not because of the superiority of either argument. [strike that last bit if it bothers you] [LOL]

I concede the outcome, but not the battle or the principle.

Thank you, ’nuff sed

Steve;

It should have read “a simple “Yes” reply would suffice“ to the actual question …which was… “Can I assume that was not the case?” no offense!

So, what’s the compelling reason to change a system that has worked very well so far? I get that there are people still sour on the 200 election, but that’s not a good reason to change a system that has worked well. The last time before 2000, remember, that the electoral college differed from the popular vote was 1888. Only three times in our history has a President not carried the popular vote (I’m throwing out Jackson as his was a very special case). So, that’s 3 out of 56 elections, which means that we can expect to see this aberration every 76 years. It has been, on average almost literally, a once in a lifetime event. Since two of those events happened in 1876 and 1888, it’s safe to say that the vast majority of Americans who have ever lived have seen it happen.

But we want to change that reliable a system? No, I don’t get it.

Jimmie: I don’t think a system devised to ignore the majority of the electorate works well.

Jimmie;

Nor Do I.

Raoul;

Nor Do I.

Pardon me jimmie.