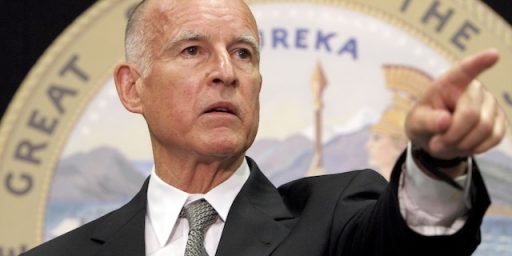

Jerry Brown’s Game

NYT Magazine has an interesting profile of a man who was governor of California when I was in middle school–and again now that I’m in middle age.

Adam Nagourney (“Jerry Brown’s Last Stand“)

The 39th, and 34th, governor of California was making his first trip to Los Angeles since being sworn in, for an evening speech in February to the city’s Chamber of Commerce, and a swarm of reporters was waiting at Terminal A of the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank. Edmund G. Brown Jr. — he has always preferred Jerry — arrived from Sacramento not on a state aircraft (and certainly not a private jet, as was the preference of his predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger) but aboard Flight 896 on Southwest Airlines. As Brown walked off the plane and into the terminal, he was essentially alone, save for a few police guards who hung off to the side. There were no press aides, no advance staff, no speechwriters, no policy mavens; in short, nothing like the bustling entourage of self-importance that typically buffers a chief executive.

[…]

Term limits, the new governor suggested to me a few weeks after taking office in January, have turned out to be a force for bad, feeding the paralysis in Sacramento. Over late-night glasses of pinot grigio and plates of brussels sprouts at a restaurant near the State Capitol, he talked about lawmakers who now spend so much time worrying about getting elected to another, higher office that they have little time to consider the staggeringly complicated legislation that lands on their desks or to build working relationships with other lawmakers.

“The experts have taken over,” Brown told me, referring to the more permanent class of legislative aides and lobbyists. “The elected people are the ones who ought to be thinking about this, but they are all thinking about their next job. It has actually created more insecurity and less independence on the part of representatives.” The days when legislation could be drafted by five elected officials in a room — the governor and the majority and minority leaders of each party — are gone. The lawmakers and staff members who ran the place when Brown last served as governor are also, for the most part, gone.

[…]

On one side of the Ronald Reagan Cabinet Room, as it is officially known, there was an almost-12-foot-long picnic table made of fir, along with two hard, backless benches. In its severity, the table invites comparisons with Schwarzenegger’s décor; his offices were furnished with a sword from his days as Conan the Barbarian. The unforgiving benches discourage lingering or bloviating, which is why they are there: Brown is not one for long meetings. There is a daily 8 a.m. conference call with a small group of his senior staff, but Brown almost willfully refuses to participate, reading the morning political news on Anne’s iPad as she, sitting in their Sacramento loft over breakfast, deals with the call.

He is more apt to impulsively pick up the phone to call a lower-level commissioner than agree to a scheduled briefing with a department head. “He is not someone into structure,” Anne says. “Not at all.” Decisions about where and when to go tend to be so last-minute that the police guards who accompany him make backup reservations on later flights for the governor on Southwest. Routine newspaper requests for his appointment calendars are exercises in futility; Brown does not live by a calendar. When it came time to propose major policy positions in the campaign, “it would be me and Jerry sitting at the computer,” Anne said. “And he would call a bunch of guys, and I’d be sitting there saying: ‘Education. What is your policy on education?’ We’d work out a framework together, and he called a lot of experts. He knows a lot of people.”

[…]

Brown cut his own staff 25 percent in an early sign of austerity. “He doesn’t need speech writers, policy ghostwriters, political consultants — he doesn’t need a lot of us,” said Steve Glazer, his top political consultant. Brown refused to name a chief of staff, mocking the very concept. “What is a chief of staff?” he demanded sarcastically when I asked him about it. “What is that? Everybody begins to think they are the president or governor or something.”

For this governor, no task seems beneath him, be it adjusting the thermostat in a meeting room or handling scheduling requests for his wife.

[…]

This stripped-down style has set a tone that seems right for these times. Small cuts, like reducing the number of cellphones and state cars, could easily have been lampooned as gimmickry but instead have resonated well on both sides of the aisle. With legislators, Brown’s approach is one of nonchalant informality, as he sets out to recruit rather than confront. The contrast with his predecessor has proved something of a gift. “He’s very unpretentious,” Steinberg, the Democratic Senate leader, said. “He comes into our caucus lunch yesterday, and he doesn’t sit down, he gets on the food line.” Steinberg’s Republican counterpart, Bob Dutton, said Brown called him right after the election. “He offered to come down to me, and I said, ‘You’re the governor-elect, I should come to you.’ ” They met at Brown’s office in San Francisco. Aides who work in the Assembly speaker’s office in downtown Los Angeles talk of answering a knock on the door to find the governor, alone, having wandered from his Los Angeles office in the same building, searching for the speaker.

[…]

None of this is to say Brown is undisciplined. From speeches to news conferences to meetings with lawmakers, he has meticulously made his case for solving the state’s budget crisis. He proposed eliminating a $26.6 billion shortfall with nearly equal measures of spending cuts — to public schools, higher education, health care programs for the elderly, economic-redevelopment funds for communities — and extensions of modest surcharges on the state’s income tax (0.25 percent), sales tax (1 percent) and automobile registrations (0.5 percent) that would otherwise expire. More than $10 billion in cuts have already been signed into law. But if he cannot win approval for those taxes, he says he will close the rest of the gap by cutting spending further, declaring that he would not sign a budget that papers over the shortfall with fiscal trickery.

[…]

Brown is confronting many of the same obstacles that burden governors across the country. But because of the magnitude of the dollars in question and the essential collapse of California’s system of government, his situation seems more dire, more intractable. The state’s $26.6 billion shortfall was the equivalent to almost a third of next year’s budget. Brown promised during the campaign that he would not raise taxes without putting it before voters. To do that, short of gathering signatures, he would need to win the support of two-thirds of the Legislature, which means finding four Republican votes. Republican governors like Chris Christie of New Jersey, Scott Walker of Wisconsin and John Kasich of Ohio have chosen confrontation in the face of their budget upheaval, but Brown — who was certainly a bomb-thrower in his day — has been as calm and patient as the Jesuit student he once was, solicitous of his opponents and, at least in appearance, their ideas: sharp spending cuts, reductions in pension benefits for union workers, deregulation. “Scapegoating is very powerful stuff,” he told me during a break in negotiations with Republicans in March. “But I think it divides at a time we need to unify. It’s very short term. You want to push, but you also have to include.” As he has gone from lawmaker to lawmaker making his case, he has avoided ultimatums and threats, remaining calm if unwavering. “He has made it very clear, ‘If you don’t like elements to my program, you can’t just say no to them,’ ” Pérez, the Assembly speaker, told me. ” ‘You have to come up with an alternative that creates comparable savings.’ ”

[…]

In our conversations over the last few months, it became clear that Brown is considering, in the event of failure, a subversive notion, a last-stand response to the Republican agenda of blocking the tax extensions and forcing spending cuts: Let it happen. “If you talk about taxes, you don’t get elected — so that’s a nonstarter now,” he told me. “You have to keep cutting to the point where people say they want to increase their contribution.”

In other words, the only way a majority of Americans might reconsider taxes is if they experience the full brunt of spending cuts, not only in California but also in Washington. “People have never experienced cutting like that before,” Brown told me. “That will create turbulence.” If raising taxes is a nonstarter in this environment, change the environment.

I don’t share much of Brown’s ideology but I rather like his style. There’s certainly something liberating about not caring whether you get re-elected.

What a crock! In his previous incarnations, he damn well had his eyes on the next job too. He’s only sanctimonious about it now because he’s 73 years old, but back then he ran for president several times!

As for his brinkmanship, we are yet (in both California and more broadly in the entire US) damn well going to “experience the full brunt of spending cuts”, only we don’t HAVE the capacity to tax any more. Let’s see how THAT pans out.

Oh really? How’s that?