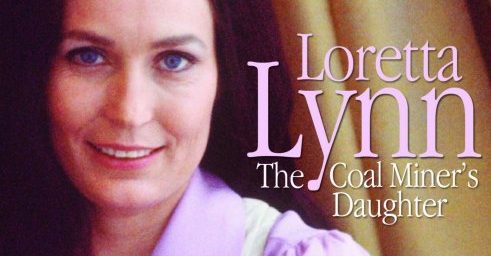

Loretta Lynn, 1932-2022

A country music icon is gone at 90.

Billboard, “Loretta Lynn, Country Music Icon, Dies at 90“

Vocalist Loretta Lynn, whose ascent from a small Kentucky coal-mining community to national country music stardom literally became the stuff of Hollywood, died on Tuesday (Oct. 4) at 90. According to a statement from her family, Lynn passed away in her sleep at her home in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee.

[…]

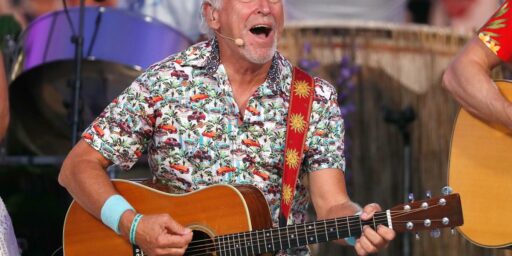

Lynn’s life story was memorably retold in Michael Apted’s 1980 feature Coal Miner’s Daughter, based on Lynn’s 1976 memoir. Sissy Spacek won both a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for her portrayal of the singer.

Beyond the dramatic particulars of her life, Lynn, who recorded 16 No. 1 country singles, was among the music’s groundbreaking female singing stars.

She became one of the music’s brightest luminaries in an era when men dominated country. She wrote much of her hit material, and it was sharply-penned stuff, written from the point of view of a woman (usually a married one) who would take no guff from her man. And she did not shrink from controversial subject matter.

Lynn was born Loretta Webb on April 14, 1932 in Butcher Hollow, Kentucky. “I’m always making Butcher Hollow sound like the most backward part of the United States — and I think maybe it is,” she wrote in her autobiography.

She was the second eldest of coal miner Melvin Webb’s eight children, and grew up in sometimes dire poverty in the heart of the Great Depression. One of the few distractions she had was the radio; 11-year-old Loretta became enamored of the Grand Ole Opry and its early female star, Molly O’Day.

At the age of 14, she married Oliver Lynn, known by his nicknames “Doolittle” and “Mooney.” A year later, the couple moved from Kentucky to Custer, Washington, a town of a few hundred near Bellingham. By 18, Lynn had four children. (Two more would follow later.)

Encouraged by her husband, Lynn began singing in the Washington clubs. In 1950, Don Grashey of tiny Zero Records arranged a session for her in Los Angeles. Backed by top-flight guitarists Speedy West and Roy Lanham, she cut her composition “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” inspired in part by Kitty Wells’ 1952 hit “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonky Angels.”

With tireless promotion by the country neophyte, the song became a surprise hit, and Lynn was soon touring with the Wilburn Brothers and appearing on the Grand Ole Opry. She was signed by the major label Decca Records in 1961, and the title of her first top 10 hit for the company harbingered the rest of her career: “Success.”

A run of chart-topping country singles followed, sung in a warm voice but taking a tough-minded stance. Just the titles of many of these hits telegraph Lynn’s point of view: “You Ain’t Woman Enough” (No. 2, 1966), “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ On Your Mind)” (No. 1, 1966), “What Kind of a Girl (Do You Think I Am?)” (No. 5, 1967), “Fist City” (No. 1, 1968), “Your Squaw is On the Warpath” (No. 3, 1968).

Other signature tunes by Lynn took an autobiographical tack; these included 1965’s “Blue Kentucky Girl” (memorably covered by Emmylou Harris) and 1970’s No. 1 single “Coal Miner’s Daughter.”

In 1971 — the year she charted her biggest solo hit, “One’s On the Way” — Lynn began a productive collaboration with label mate Conway Twitty. The pair’s No. 1 duet hit “After the Fire is Gone” was followed by a dozen more top 10 country singles.

In 1975, as the national debate over women’s liberation continued to roil, Lynn incited comment with her song “The Pill.” The song, which reached No. 5 on the country chart, was, in Lynn’s words, “about how the man keeps the woman barefoot and pregnant over the years.” It was one of the best examples of the no-nonsense spunk of her songwriting.

Lynn continued to chart records through the ’80s, but her recording career slowed and then stopped.

She reentered the scene at the age of 70 in 2004 through the agency of an unlikely fan and collaborator, Jack White, of the popular Detroit garage-punk act The White Stripes. Lynn and White collaborated on the Interscope album Van Lear Rose, which was designed to reignite her career as Johnny Cash’s series of American Records albums had returned him to prominence. The album became the biggest of her career, and the Lynn-White duet “Portland Oregon” received serious radio play.

Lynn remained active well into her 80s, releasing the Grammy-nominated Full Circle in 2016, the first of a series of albums produced by her daughter, Patsy Lynn Russell and John Carter Cash. Circle was followed by that year’s White Christmas Blue and and 2018’s Wouldn’t It Be Great, a collection of new songs and interpretations of classics including the title track, “God Makes No Mistakes,” “Don’t Come Home a Drinkin'” and “Coal Miner’s Daughter”; a planned tour was canceled after Lynn suffered a stroke in May 2017.

The singer returned in 2021 with the her 46th and final album, Still Woman Enough, which featured “Coal Miner’s Daughter Recitation,” a celebration of the 50th anniversary of her signature song.

Rolling Stone, “Loretta Lynn, Country Music’s Groundbreaking ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter,’ Dead at 90“

LORETTA LYNN, THE beloved singer and songwriter whose seven-decade career broke down barriers for women in country music, died Tuesday at her home in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. She was 90. Lynn’s publicist confirmed her death to Rolling Stone.

[…]

In the 1960s, Lynn’s trailblazing country chart-toppers established the model of the female country star as an independent woman who stands her ground against cheating men and no-good homewreckers with unflagging, good-natured spirit. Lynn adapted her autobiographical 1970 hit “Coal Miner’s Daughter” into a bestselling biography, which was later made into an Oscar-winning film, introducing the story of a hardscrabble upbringing in Depression-era Kentucky that Lynn celebrated to people who never even listened to country music.

“So sorry to hear about my sister, friend Loretta,” tweeted Dolly Parton, who joined Lynn and Tammy Wynette on the 1993 album Honky Tonk Angels. “We’ve been like sisters all the years we’ve been in Nashville and she was a wonderful human being, wonderful talent, had millions of fans and I’m one of them.”

[…]

Lynn wrote most of her hits, and as the first female singer to make her name as a songwriter in Nashville, she paved the way for modern artists like Miranda Lambert and Taylor Swift.

[…]

In the late 1950s, Lynn started writing songs on her $17 Sears Roebuck guitar and, with Doo as her manager, performing them in local bars. In 1960, the 27-year-old Lynn recorded “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl” and traveled around the country with her husband, promoting the song at radio stations so successfully it became a Number 14 country hit. The Lynns soon worked their way to Nashville, where Lynn made her first appearance at the Grand Ole Opry before the end of the year.

Lynn signed with Decca Records, where she began a long and fruitful working relationship with producer Owen Bradley, who had recorded Patsy Cline’s hits. In 1962, “Success” became the first of 16 Top 10 country hits Lynn would release in the Sixties, most of which she wrote or co-wrote. And in 1967, she became a full-fledged country star when her song “Don’t Come Home a’ Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” became her first Number One hit; the album of the same name became the first gold record by a female country performer. That year, Lynn won the Country Music Association’s first Female Vocalist of the Year award.

As the title of her 1970 album Loretta Lynn Writes ‘Em & Sings ‘Em made clear, Lynn’s popularity was partly due to her songwriting gifts. Fans had the sense that she was essentially singing the story of her own life, and on her first hit of the 1970s, “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” that was literally true. “I wasn’t sure that it would ever be heard,” she said of the song. “But it was about me, so I sang it and it made a hit.”

Also in 1970, Lynn kicked off a hugely successful recording and touring partnership with Conway Twitty, a rock & roll player turned country heartthrob. Starting with “After the Fire Is Gone” in 1971, the duo’s first five singles all went to Number One, and their next seven singles made the Top 10. From 1972 to 1976, Lynn and Twitty prevailed over Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton and George Jones and Tammy Wynette to win the CMA’s Vocal Duo of the Year.

In addition to her duets with Twitty, Lynn had 24 country hits in the 1970s, all but two of which hit the Top 10 and eight of which were Number Ones. Lynn fearlessly expanded the range of topics her songs addressed, and a few were outright controversial. “One’s on the Way,” written by Shel Silverstein, had Lynn portraying a pregnant Topeka housewife who muses over women’s lib marches and celebrity gossip, while “Rated X” blasted the stigma facing divorced women. Both went to Number One, while the Number Five hit “The Pill,” which Lynn wrote herself, unequivocally celebrated birth control. “I never had the money to buy the pill. If I had it, I wouldn’t have had a bunch of kids,” she joked. “But I’m glad I had a bunch of kids. I wouldn’t take nothing for my family.”

Despite her consistent messages of empowerment, Lynn was wary of politics and resisted aligning herself with the feminist movement. “I’m not a big fan of Women’s Liberation,” she wrote in Coal Miner’s Daughter, “but maybe it will help women stand up for the respect they’re due.” She also famously dozed off during The David Frost Show while Betty Friedan was speaking.

Lynn’s willingness to take on tough subjects only increased her appeal, and in 1972 she became the first woman to win the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year Award. In 1976, Lynn achieved an even greater level of success when she released her autobiography, Coal Miner’s Daughter, written with New York Times reporter George Vecsey. One of the 10 biggest-selling books of 1976, it was adapted into a popular and critically acclaimed 1980 movie starring Sissy Spacek, who sang Lynn’s songs in the film and won the Best Actress Oscar.

Lynn scored her last Top 10 country hit in 1982, and her sales dipped over the course of the decade. In 1988, the same year she was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, she put her career on hiatus to nurse her ailing husband. When Oliver Lynn died in 1996 from diabetes complications, they had been married 48 years, and not always happily. In interviews, Oliver was frank about his alcoholism and infidelity. The Lynns’ marriage was famously stormy, and Doo’s heavy drinking and infidelities were widely known. In 2000, she recorded her tribute to him, “I Can’t Hear the Music.”

New York Times, “Loretta Lynn, Country Music Star and Symbol of Rural Resilience, Dies at 90“

Loretta Lynn, the country singer whose plucky songs and inspiring life story made her one of the most beloved American musical performers of her generation, died on Tuesday at her home in Hurricane Mills, Tenn. She was 90.

[…]

Ms. Lynn built her stardom not only on her music, but also on her image as a symbol of rural pride and determination. Her story was carved out of Kentucky coal country, from hardscrabble beginnings in Butcher Hollow (which her songs made famous as Butcher Holler).

[…]

Her voice was unmistakable, with its Kentucky drawl, its tensely coiled vibrato and its deep reserves of power. “She’s louder than most, and she’s gonna sing higher than you think she will,” said John Carter Cash, who produced Ms. Lynn’s final recordings. “With Loretta you just turn on the mic, stand back and hold on.”

Her songwriting made her a model for generations of country songwriters. Her music was rooted in the verities of honky-tonk country and the Appalachian songs she had grown up singing, and her lyrics were lean and direct, with nuggets of wordplay: “She’s got everything it takes/To take everything you’ve got,” she sang in “Everything It Takes,” one of her many songs about cheating, released in 2016.

[…]

Jack White, the singer and guitarist of the White Stripes, said in an interview with The New York Times in 2004, the year he produced Ms. Lynn’s Grammy-winning album “Van Lear Rose,” that she “was breaking down barriers for women at the right time.” Her songs, Mr. White said, had a message: “This is how women live. This is what women are thinking.” And Ms. Lynn, he added, was taking these strides “in the country realm, where a lot of women weren’t able to do what they wanted.”

Washington Post, “Loretta Lynn, ever a ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter,’ dies at 90“

Loretta Lynn, the country music icon who brought unparalleled candor about the domestic realities of working-class women to country songwriting — and taught those who came after her to speak their minds, too – died today at her home in Tennessee. She was 90 years old.

[…]

Ms. Lynn’s career was remarkable for its storybook ascent from hardscrabble origins. She was a teenage bride and mother, a country star and a grandmother by her early 30s. A trailblazer for other female country performers, she was the first woman to win the Country Music Association’s entertainer of the year award, in 1972. She also helped redefine and broaden the appeal of country music.

“She was the groundbreaking female singer-songwriter in country music,” Robert Oermann, co-author of “Finding Her Voice,” a study of women in country music, told The Washington Post in 2003. “Her songs were delivered from a distinctly female point of view, and that had not been done before, not the way she did it. Writing about women as they really lived — that was a breakthrough.”

In 2013, when Ms. Lynn received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, President Barack Obama called her the “rule-breaking, record-setting queen of country music” who “gave voice to a generation, singing what no one wanted to talk about and saying what no one wanted to think about.”

[…]

For all the turbulence in their relationship, Ms. Lynn credited her husband with pushing her to become a performer.

“I married Doo when I wasn’t but a child, and he was my life from that day on,” she said in “Still Woman Enough,” written with Patsi Bale Cox. “He thought I was something special, more special than anyone else in the world, and never let me forget it. That belief would be hard to shove out the door. Doo was my security, my safety net.”

NPR, “Loretta Lynn, country music icon, has died at 90“

Loretta Lynn, the country music icon who brought unparalleled candor about the domestic realities of working-class women to country songwriting — and taught those who came after her to speak their minds, too – died today at her home in Tennessee. She was 90 years old.

[…]

“The story of Loretta Lynn’s life is unlike any other, yet she drew from that story a body of work that resonates with people who might never fully understand her bleak and remote childhood, her hardscrabble early days, or her adventures as a famous and beloved celebrity,” Kyle Young, CEO of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, said in a statement. “In a music business that is often concerned with aspiration and fantasy, Loretta insisted on sharing her own brash and brave truth.”

[…]

Lynn was barely a teenager when she started a family of her own with a 21-year-old former soldier, Oliver Lynn, better known as “Mooney” or “Doolittle.” They wasted no time having the first four of their six children, and migrated to Washington state. It was there that her husband heard her bedtime lullabies and pushed her to start performing publicly. In a 2010 interview with Fresh Air, she insisted she wouldn’t have done it otherwise: “I wouldn’t get out in front of people. I was really bashful and I would have never sang in front of anybody.”

Once her husband started scrounging up paying gigs for her, Lynn taught herself to write songs, says country music historian and journalist Robert Oermann.

“She got a copy of Country Song Roundup,” Oermann says – a magazine that printed country lyrics and stories about the musicians. “She would read the country lyrics in the magazine, and she’d go, ‘Well that’s nothing. I can do that.’ And she could, and had been.”

[…]

Country songs had often portrayed hardship from male perspectives, but Lynn wasn’t afraid to spell out the indignities endured in her marriage, or the double standards she saw other women facing when it came to divorce, pregnancy and birth control. She found that Nashville wasn’t accustomed to that kind of frankness.

[…]

[I]t was essential to Lynn’s enduring appeal that she never lost touch with her identity as a simultaneously modern and down-to-earth country woman who could communicate that to crowds throughout her career.

“This idea that I might be up here on stage singing this song, but I’m not better than you. I am you,” journalist Oermann says. “That’s kind of the message. That kind of humility is a really powerful and good thing.”

That approach always informed her songwriting; Lynn’s gutsiness comes through just as clearly today in the music she left behind.

“I like real life, because that’s what we’re doing today,” Lynn told All Things Considered in 2004. “And I think that’s why people bought my records, because they’re living in this world. And so am I. So I see what’s going on, and I grab it.”

Lynn was born 11 years before my parents and outlived them both. We listened to a lot of her music, particularly the Conway Twitty duet era, and saw Coal Miner’s Daughter at a drive-in theater way back when.

There is some evidence that Lynn played up her youthful marriage. While most reports have it taking place at 13 or 14—shocking modern sensibilities—her marriage records indicate it was 16. Regardless, the juxtaposition of her humble roots and hardscrabble early adulthood with her meteoric rise to stardom is something.

A Facebook friend put her on the Mount Rushmore of country artists, which probably isn’t quite right. Offhand, it would be hard to displace Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams Sr., Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, George Jones, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, and a handful of others who were stars in her heyday and before, let alone Garth Brooks and others from later eras. She’s certainly in among the top four women in country music, with only Dolly Parton almost surely ahead of her. Through sheer longevity, she outpaced her idol, Patsy Cline, and her songwriting put her ahead of giants like Reba McEntire, Tammy Wynette, and Barbara Mandrell.

A hell of a career and a hell of a life. May she rest in peace.

To repeat myself from this morning’s open forum: “Shit.”

RIP indeed.

I’d put Lynn on a country music Mt Rushmore. As an acquaintance, who was a Grammy winning performer/songwriter herself would regularly point out, Lynn was the first woman country performer to establish herself as a songwriter, singer and instrumentalist. Dolly was right behind her and she certainly had greater crossover appeal than Lynn had, but that shouldn’t diminish Lynn’s contribution to the music business.

RIP Loretta.

@Sleeping Dog: Lynn is definitely in the all-star team at the Hall of Fame. But I view Rushmore as the top four and there are so many competing for those spots.

@James Joyner:

Which is why the whole “Mt. Rushmore” meme for pop culture things is so relentlessly stupid. Everybody and their pet dog is gonna have four different choices. So Loretta Lynn isn’t on your Mt. Rushmore; WGAF and who put you in charge of deciding?

I have a tiny swell of local pride concerning Loretta Lynn. Because I grew up about 4 miles from Custer, WA, and let me tell you, describing it as a “town of a few hundred” is charitable.

It had a feed store, a bar, and a post office. Possibly the 1960’s version of a convenience store.

Now there were folks living nearby in that sort of exurban way. You know, maybe 5 or six houses per mile of road, with no housing developments to speak of.

Anyway, when we would drive over to Lynden (a much bigger and more important town than Custer) there was a joint on the way with a big sign outside that said, “Loretta Lynn started here”. I expect my grandad, who ran a club in the late 40’s and 50’s in the area, had met her, because that guy knew a lot of folks. He was fun to talk to, so people would bring their friends to visit him.

I had the good fortune to meet Loretta Lynn several times. I catered some events for the CMA and she and her sister would hang a bit with us. She was sweet and absolutely guileless and endearingly ditsy. She took leftovers back to their ranch and feed her crew.

My husband cut vocals with her. The vocal booth had three doors and they had to send the second engineer to make sure she found her way back to the control room for playback. She would end up in a mic closet or wandering the halls otherwise.

Everybody loved her.

Ohhhh Loretty. I adored her. The Queen of Country as far as I’m concerned. The sheer amount and quality of hits is without parallel: “Fist City,” “You Ain’t Woman Enough,” of course “CMD” and on and on and on. Her songs are catchy and just fun to sing along to; I think that was the key to her songwriting.

My brother and I were huge fans of the movie Carrie (and all movies from Stephen King books) as children. From there because we were now Sissy Spacek fans, we discovered CMD. Definitely wore that movie out. And that’s how we became fans of Lynn. R.I.P. Great Lady.

SPOILER ALERT!

@DK:..Carrie…

Any time I hear people say that they are going to “reach out” to someone (I hear it all the time). I always think of this scene.

I just watched it twice and it startled me both times. I’m not sure if I’ll be able to sleep tonight.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I see the debates as a way to reflect on greatness, not as a means of exclusion. That we’re having the conversation about Lynn and didn’t about, say, Tom T. Hall, Glenn Campbell, Charlie Daniels, or so many others is telling.