Mathematics of Layla

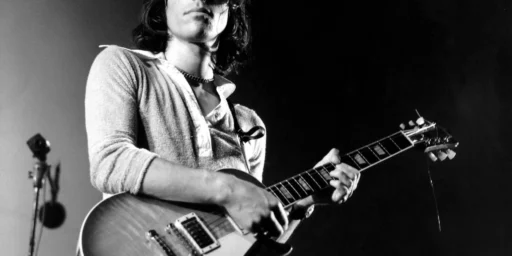

Bernard Chazelle explains “the technical part” of Eric Clapton’s classic “Layla.” Played here with an assist from Mark Knopfler, for those in need of a reminder.

The intro and chorus follow the progression of “All Along the Watchtower” (i-VII-VI-VII-i, ie here, Dm-C-Bb-C-Dm): one of the most common chord sequences in rock (0:27-1:10). The song is in Dm, but the verse begins on a C#m (1:10) ie, its antipode on the cycle of fifths. By rock standards that’s as wild as it gets. In country music, you’ll often hear a singer move up or down by a half-step for no particular reason, as though a boring tune becomes interesting just by virtue of raising its key. But Clapton knows what he’s doing. When he leaves the comfort of Dm for C#m he actually modulates to its relative major E. Just wait: you’ll see there’s method to the madness. Now when he hits the root E (1:17), you should soon be hearing a nice interrogative D (the Mixolydian quest for a change): you need it as a leading tone for the coming F#m (1:18). But Knopfler seems asleep and drops the ball, so the transition is not as compelling as it should be.

The idea then is to go through a perfect cadence twice (ii-V-I-IV, ie, F#m-B-E-A) — the kind of downwind sailing I was talking about earlier. The final A is then used as the dominant of the original key of Dm. It’s all tonally “correct.” If you’ve ever heard of the harmonic minor scale but always wondered what it was about: this is your perfect illustration. In theory, from A the reentry should be to D major, not minor. Of course, home is Dm so Clapton has no choice. The problem is that A has a C#, which is not in the scale of F (the notes of the keys of Dm are given by the scale of F), so hundreds of years ago people invented a new scale called Harmonic (common in Middle-Eastern music), which gives us a leading tone to the tonic, ie, C# -> D. Voila!

That really clarifies things, doesn’t it?

Yeah, I don’t understand it, either. So why bother posting? Because of Bernard’s point:

Why I care about such analyses: because it’s a myth to think those guys woke up one day, grabbed a guitar, and composed these tunes. They have in them, as we all do, hundreds of years of cumulative musical sensitivity that was “invented” (not discovered) by people who worked out the theory. That’s what makes western music different from all others. Since the 9th century, it’s been built as a written theoretical construction. The interplay between theory and practice is tighter than in any other art form. So to think of theory as what scholars did after the fact to understand music is naive. In the West, the theory always came first. Don’t forget that.

I think that’s right. But it doesn’t mean that, for example, Clapton or other guitar virtuosos necessarily understand and of this from a technical standpoint. But they clearly know it.

via Jim Henley’s secret blog

“But it doesn’t mean that, for example, Clapton or other guitar virtuosos necessarily understand and of this from a technical standpoint.”

No, not necessarily, but if you can read/write sheet music, you necessarily understand how this works, because the written music is the abstract theoretical model of the music. Just like I can read a sentence and see grammatical features, musicians read sheet music and see its technical elements. And just like reading, it only seems terribly complicated if you don’t know how to do it.

But writing — let alone truly excellent writing — is much harder than reading. But there are probably world class poets and novelists who don’t know how to diagram a sentence.

Not sure about Clapton, but nearly all the jazz greats do.

Steve

There is some good backstory on Laya on the “Tom Dowd & the Language of Music” DVD, which is highly recommended.

Another example

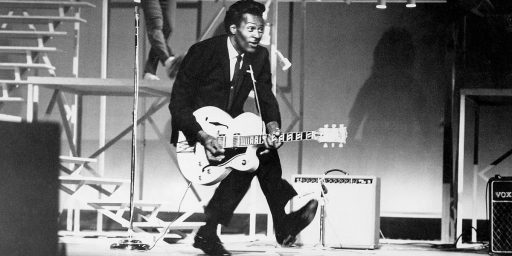

Look at the music credit on sheet music for The Beach Boys Surfin USA.

Chuck Berry (Sweet Little Sixteen)

Of course Berry had to threaten lawsuits before they gave him credit and most of the royalties.

We should be careful to make a distinction between something that is derivative, something that is a tribute, and something that is a ripoff.

Clearly, many black (and white) artists have been ripped off. A bad practice, and its victims deserve compensation.

Almost everything is derivative to some extent, there are just not that many truly original ideas (all the more reason to embrace them when they do come along).

Then there is a tribute. When Steely Dan use the into to “Song for my Father” in “Rikki don’t lose that number”, they were accused of ripping Horace Silver off. Not true. Becker & Fagan are huge jazz buffs who love Silver’s music. They were paying a tribute to him & they introduced a lot of people to his music in the process.

I don’t know if Hendrix or Clapton could/can read music or are technically fluent (probably best not to conflate the two things; one can conceivably read well enough to play from sheet music in real time, and still not understand harmony at a technical level); regardless, I imagine it’s possible to get as far as they did without any training or reading in theory.

But that’s about it. Harder to imagine becoming a virtuoso like Miles Davis (Julliard for one year, then dropped out to join Charlie Parker’s group) without formal training, let alone an orchestral composer/arranger like Ellington or Gershwin.

You know, lines like this really piss me off. China had written music before the Birth of Christ–indeed, the government of China had an office whose sole job was to preserve music way back in the Qin Dynasty. Chinese music theory is well developed, and its traditions are rich and complex.

Ah, but we westerners always have to assume that we do everything the best, right? Don’t even get me started on the standard history of science textbooks which seem to believe that the scientific method was spontaneously developed by Bacon with no mention of the Arabian systemization of physics, medicine and chemistry.

A lot of musicians, particularly guitar players, don’t “read†music as in the shaped notes on a staff. The guitar lends itself to patterns more than just about any other instrument and more confusing to read sheet music because there is more than one way to play the exact notes written on a page. Sight reading sheet music written for guitar is a skill separate from the other aspects of playing the instrument and understanding the music theory. There are a lot of good players who can’t read sheet music (preferring tablature to get the precise fingerings) but anyone who has been around music as long as these guys playing professionally knows the theory (all that I-IV-V, dominant, sub-dominant stuff).

So whether Clapton or Hendrix could read a guitar part from sheet music is irrelevant (Obviously they could read sheet music with the chords written and in fact most studio parts have the chords written out so a rhythm really doesn’t have to bother reading the notes). Guitar players are typically the ones who understand the theory (as opposed to horn players for instance) the best because they are playing chords rather than single line melodies and that’s how they communicate with each other.

Purple Haze is a textbook example of the use of a diminished scale in a melody; Hendrix knew that and could have easily came up with the tune practicing that scale. The opening notes of my girl are the first few notes of a second position (on the guitar) pentatonic scale. The opening notes of the Jaws theme are a great example of a minor 2nd interval. If you listen to a lot of guitar players you start to find out what there favorite scale modality is. Santana seems to like the Aeolian mode; Jerry Garcia favored the Lydian and Mixolydian mode. Every guitar player on the planet can play the pentatonic scale in just about every position on the neck.

Clapton is well schooled in theory as is just about anyone who ever played guitar professionally. There are a few exceptions but those are people that either played very simple accompaniment or had devastating memories.

Actually, John Mellencamp got there earlier and pithier: “Forget all about that macho shit and learn to play guitar”

I don’t know much about that music theory, but THIS is what every rocker knows:

“….I shoulda learned to play the guitar,

I shoulda learned to play them drums

Look at that mama, she got it stickin’ in the camera..man we could have some…

And he’s up there, what’s that? Hawaiian noises?

Bangin’ on the bongoes like a chimpanzee

Oh, that ain’t workin’ that’s the way you do it

Get your money for nothin’ get your chicks for free….”

;->

Jesus, Clapton is awful and Layla should be renamed “Lame-la.”