Nick Saban Has Been Nick Saban A Very Long Time

In "Eyes on the Prize," Chuck Culpepper looks at Saban's first season as a head coach, with Toledo, way back in 1989-90. It seems that Nick Saban has been Nick Saban for a very long time.

In “Eyes on the Prize,” Chuck Culpepper looks at Saban’s first season as a head coach, with Toledo, way back in 1989-90. It seems that Nick Saban has been Nick Saban for a very long time.

Said Mike Karabin, the deputy athletic director at the time, “In the interviews you could just see from the way he described how he’d run the program, he was a little bit different from everybody else.”

For one thing, there was the “booklet,” as [Kevin Meger, Toledo’s then sophomore quarterback.] called it. The “booklet” had about 500 pages. “I’ve still got it, probably in the basement,” he said. The booklet: “This is how you’re going to dress. This is how you’re going to act. This is how you’re going to function. And this is the motivating reason behind it.”

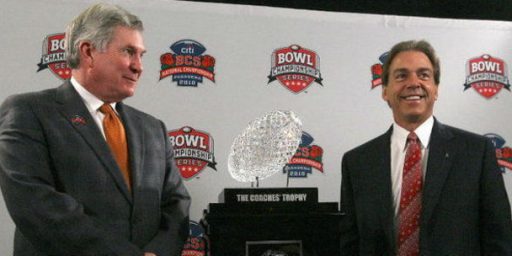

Many coaches have considerable clarity, and surely many, many coaches have booklets, but only one active coach has the Alabama job, three national titles, the 2011 national title and a 9-2 record in one season at Toledo for a share of the 1990 Mid-American Conference title. The same coach who will lead Alabama against Georgia on Saturday for the SEC Championship and a shot at the national title.

[…]

In the seventh game of that 1990 season, Toledo lost 13-12 at Central Michigan, and Saban seemed devastated beyond devastated, of course. Sunday morning promised the Sunday morning film session. Players cringed, but: “He reacted better to a loss than to a win,” Meger said. “It was a different reaction than I think the team expected. I think we expected the guy on television that you see. And we didn’t get that guy. We got a very calm, very surgeon-like individual.”

When the season began, and the eight-station, 64-minute morning workouts began, and the repetitions of same if anyone loafed began, and the players started thinking, “He’s a nasty man, dude!” (Meger’s words), practice scuffles began. Previous coaches would have intervened. Saban’s assistants tried to intervene. Saban chewed them out. “Let the players clear it up!” he barked. “He said, ‘If you’re going to fight, then do it with excellence,'” Meger recalled. “‘Don’t waste my time with all this small stuff.'”

Meger watches Alabama on TV when possible, and he notices the same things, and not just that Saban still talks with his hands. “They are playing to be excellent,” he said. “They’re not playing to beat the opposition. They’re not playing to win. They’re playing to be excellent. And if I’m excellent, I win more than you do.”

[…]

So while Saban gains no note for any signature tactic, his specialty probably would be a special level of zeal, the deathless urgency that leads him to berate players at moments not urgent to others (such as blowout fourth quarters). “Never take a play off,” Meger still notices. “You’ll never see a kid loaf on that football team — special teams, backup, whatever.” Said Meger, “I would say he’s no more content today than he was in 1990. Most people get complacent. To have this level of focus for this long is rare.”

[…]

“I had family trouble at home, and he knew I had family trouble at home, and he got involved, by no means in an illegal way,” Meger said. “I can remember him telling me, ‘I thought it was the right thing to do.'”

When Meger’s grandmother neared death while two-a-days persisted back at Toledo, the quarterback feared telling the head coach but mentioned it to a graduate assistant, who told the head coach, who turned up at the dorm room ready to deliver Meger to the hospital if necessary. (An assistant drove him.) Meger still believes he could call Saban for a favor and get a “What-do-you-need” in reply even though they have lost touch for 15 years.

Looking for the photo atop this post, I found an August Toledo Blade story shedding more light on that one season with the Rockets:

Saban didn’t immediately revolutionize college football. Yet he took an approach to academics and athletics that at the time was considered progressive.

Recently chronicled in Sports Illustrated, it’s an approach that emphasizes accountability, professionalism, a high level of intensity, and a thorough work ethic. And it’s now a prototype.

Florida coach Will Muschamp calls Saban’s modus operandi “the blueprint.” And if Saban operates under a blueprint, then consider the 1990 season a drafting table.

“Everything we do now, we tried to do the same things at Toledo,” Saban said. “We have the same kind of academic support program we tried to implement, relative to the resources we had. Philosophically, we practiced the same way, recruited the same way and looked for the same thing in players, and tried to have the same kind of team.

“I think the team at Toledo probably reflected that, how they played, how they responded, how they did. We’ve learned a lot through the years, but we really haven’t ever changed our philosophy from the first year at Toledo.”

Coaching the Rockets was a chance for Saban to prove he was capable of running his own program, and a chance to experiment with a plan that he believed could produce a well-rounded program and a more holistic student-athlete.

“It may have been a little progressive,” said Rusty Hanna, a Northview High School graduate who was a kicker for Saban. “At that time, a lot of guys I played with and even my mentality, I wanted to play college football. That was my main desire. Not that school came second. I took it serious. But a lot of guys I knew were there just for football. At that time, [Saban’s stance] may have been progressive, but it was very important. He saw that academics is important, and you’ve got to stress that first.”

That emphasis came at a time when some football programs focused solely on the “athlete” part of the student-athlete equation.

“He was a little bit ahead of his time about that demand,” said former Toledo coach Tom Amstutz, who was an assistant to Saban. “He wanted the players to do well, he cared about them, and he wanted them to get their degree.”

Saban’s belief in instilling and maintaining high academic standards for the Rockets was also a testament to his upbringing in a blue-collar town south of Pittsburgh.

“He was a poor kid from West Virginia, and a college degree meant a lot to him,” Amstutz said.

Saban comes across as a jerk and something of a cold fish. And, as a practical matter, maybe he is. But it’s a function of a single-minded obsession with what he dubs The Process—that pursuit of excellence in daily activity rather than simply a focus on results. His disdain for questions about outcomes in press conferences, for example, is simultaneously dickish—he wouldn’t be making millions of dollars a year if not for fan enthusiasm, which is fueled by press coverage—and genuine. He simply finds anything that takes focus away from The Process to be intolerable.

I’m still a bit curious why Saban left Michigan State. I suppose at the time his goal was to get to the pros. But there’s no real reason why he couldn’t have done at MSU what he’s done at Alabama. And I say this as a Wolverine fan, an in-state rival.

Other than over-signing, and bailing on MSU before their bowl game in 1998, I don’t really have much opinion of the guy. It’s obvious he can win, and he will likely go down as an all-time great unless some major scandal brings him down.

@Franklin: I think LSU was a pretty clear step up from MSU. First of all, MSU will always be the number two program in the state. Michigan is one of the four or five most storied programs in the country and will always have the recruiting advantage. LSU is the only major program in Louisiana. Second, the South is a much more fertile recruiting ground. Third, I’m pretty sure the pay was better. While the Big Ten has caught up somewhat owing to the Big Ten Network, the SEC was a much richer league 12 years ago and it divides bowl revenue equally.

A Notre Dame-UGA title game, I’d happily root for both teams.

A Notre Dame-Bama title game, I paint my house green.

@James Joyner: My only hedged argument is against your first point. Yes, Michigan is primarily a football school. But there was a time and there may soon be a time again soon that they care about basketball. And yet the dominant basketball team in the state is MSU with Tom Izzo. If Saban had remained, there would have been quite the rivalry.

I believe you on the third point, although I wasn’t really aware there was that much difference. I did know that Michigan’s coaches have always been relatively underpaid, but they don’t seem to mind due to the prestige.