No, John Bolton Didn’t Break the National Security Council

Yes, he was terrible at his job. But one can't break that which is already broken.

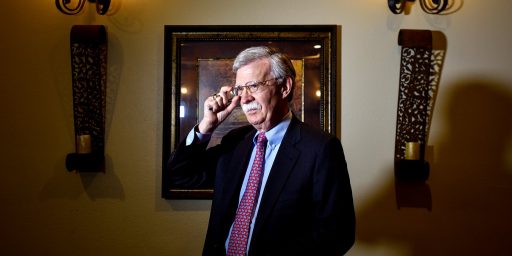

University of Pennsylvania scholar John Gans articulates for the New York Times “How John Bolton Broke the National Security Council.” The essence of his argument:

To pursue his own policy agenda and serve an erratic president, in just 17 months Mr. Bolton effectively destroyed the National Security Council system, the intricate structure that governed American foreign policy since the end of World War II. Mr. Bolton’s most lasting legacy will be dismantling the structure that has kept American foreign policy from collapsing into chaos, and finally unshackling an irregular commander-in-chief.

[…]

Driven by confidence in his own ideas about what government should do and how it should run, he had in mind something closer to Roosevelt’s juggling: The president in a room with the national security adviser and a few aides making decisions about most important issues in the world. To realize that plan, Mr. Bolton included fewer people in meetings, made council sessions far less regular, and raced to always be by Mr. Trump’s side. There was no longer a National Security Council, in effect, just a national security adviser.

While this is a compelling argument, it’s wrong.

To be sure, Bolton was an awful National Security Advisor. And I have no doubt he assiduously bypassed the staffing process that predominated under recent Presidents to ensure that his personal policy preferences made it to Trump’s ear. But it had no real impact on Trump’s foreign policy and there’s no reason that it’ll have any lasting impact on the NSC, which has no real corporate existence in the way of the cabinet departments it ostensibly helps coordinate.

First, as Kori Schake has brilliantly articulated, “the optimal choices for any administration are those that work with the grain of the president’s management style. Textbook practices that are starkly at odds with how the president is comfortable making decisions will result in circumvention of the formal decision-making process until practices are found that suit the president’s needs.”

Schake quotes George W. Bush’s second National Security Advisor, Steve Hadley’s observation, “Presidents get the national security process they deserve.”

It’s true, as Gans lays out, that Trump came to the White House with even less experience in the ways of Washington than most of his predecessors and therefore desperately needed a well-orchestrated interagency process. But he’s made it clear from the get-go that he didn’t want one. He’s smarter than his generals, much less the swamp-dwelling denizens of the Deep State.

Because of that predisposition, the NSC simply can’t function. It wouldn’t have mattered if Brent Scowcroft, whose second stint in the post under President George H.W. Bush is widely-considered the exemplar, were running the process rather than Bolton.

Indeed, to quote Schake yet again, “the Scowcroft model didn’t just work because Scowcroft was good at his job; it worked because everybody in the Bush administration was good at their jobs.”

Rex Tillerson was a disaster at State for a variety of reasons, not least of which was his inability to work with Trump. His successor, Mike Pompeo, is better but the President isn’t particularly interested in what State can do for him.

Jim Mattis was widely praised as one of the “adults” in the NSC room and had Trump’s ear for quite some time. But, while I prefer his vision of national security policy to Bolton’s, having a single wise man as the only advisor to whom the Commander-in-Chief will listen is not a process.

Second, and perhaps more importantly for the long term, the fact that the NSC isn’t working well—or even at all—under Trump doesn’t mean that it’s broken, much less irreparable. While this President has taken it to extreme lengths, previous occupants of the Oval Office also took a kitchen cabinet approach. John Kennedy famously preferred the counsel of his brother Bobby and Richard Nixon listened mostly to Henry Kissinger. The system quickly snapped back into place when their successors wanted a more structured approach.

Unlike State, DoD, or the CIA the NSC isn’t a permanent organization that requires years to recover from bad decisions. Trump’s decision to under-man State, for example, has created a talent gap that can’t quickly be repaired by the next President. But the NSC is simply a collection of political appointees overseeing a talent pool of professionals seconded from the various agencies.

A President who wants an effective process would merely need to appoint effective people, let them build a team, and then listen to their advice. Otherwise, they get the foreign policy they deserve. And, of course, so do we.

Martin Longman at Progress Pond has a nice headline that summarizes the issue:

To your point about Kissinger, James, what do you think the chances are that Trump has Pompeo take over NatSec? PoTUS has already shown that he’s comfortable with people occupying two roles at once.

@mattbernius: It’s, as you suggest, not without precedent. I don’t have issue with it, to be honest, because of that and because it just doesn’t matter. No process can be devised to save us from a President who ignores it.