No, the Electoral College Wasn’t About Slavery

Princeton historian Sean Wilentz lays to rest a pernicious idea propagated by . . . Princeton historian Sean Wilentz.

Sean Wilentz, NYT (“The Electoral College Was Not a Pro-Slavery Ploy“):

I used to favor amending the Electoral College, in part because I believed the framers put it into the Constitution to protect slavery. I said as much in a book I published in September. But I’ve decided I was wrong. That’s why a merciful God invented second editions.

Like many historians, I thought the evidence clearly showed the Electoral College arose from a calculated power play by the slaveholders. By the time the delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 debated how the president ought to be chosen, they had already approved the three-fifths clause — the notorious provision that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person to inflate the slave states’ apportionment in the new House of Representatives.

Ahem. It’s normally referred to as the “Three-Fifths Compromise” because it worked two ways. Yes, it greatly advantaged slave-holding states in terms of apportionment. But it also meant that those states had to pay a head tax to the Federal government, the primary form of revenue aside from tariffs prior to the Sixteenth Amendment.

The Electoral College, as approved by the convention in its final form, in effect enshrined the three-fifths clause in the selection of the president. Instead of election by direct popular vote, each state would name electors (chosen however each state legislature approved), who would actually do the electing. The number of each state’s electoral votes would be the same as its combined representation in the House and the Senate.

By including the number of senators, two from each state, the formula leaned to making the apportionment fairer to the smaller states.

Oh, for goodness sake. It had nothing to do with fairness. Indeed, it’s fundamentally unfair to give states with fewer people the same voting power in the Senate. Doing so was, again, a compromise. The status quo was the Articles of Confederation, under which each of the several states was a sovereign equal. The smaller states simply would not have acquiesced to representation based solely on population with that as the fallback.

Including the number of House members leaned in favor of the larger states. But the framers gave the slaveholding states the greatest reward: The more slaves they owned, the more representatives they got, and the more votes each would enjoy in choosing the president.

This wasn’t an independent “reward.” It was simply a reflection of the Three-fifths Compromise having already been agreed to.

The framers’ own damning words seem to cinch the case that the Electoral College was a pro-slavery ploy. Above all, the Virginia slaveholder James Madison — the most influential delegate at the convention — insisted that while direct popular election of the president was the “fittest” system, it would hurt the South, whose population included nonvoting slaves. The slaveholding states, he said, “could have no influence in the election on the score of the Negroes.” Instead, the framers, led by Madison, concocted the Electoral College to give extra power to the slaveholders.

That paragraph is sufficiently confusing that I have no response.

If you stop at this point in the record, as I once did, there would be no two ways about it. On further and closer inspection, however, the case against the framers begins to unravel. First, the slaveholders did not need to invent the Electoral College to fend off direct popular election of the president. Direct election did have some influential supporters, including Gouverneur Morris of New York, author of the Constitution’s preamble. But the convention, deeply suspicious of what one Virginian in another context called “the fury of democracy,” crushed the proposal on two separate occasions.

How, then, would the president be elected, if not directly by the people at large? Some delegates had proposed that Congress have the privilege, a serious proposal that died out of concern the executive branch would be too subservient to the legislative. Other delegates floated making the state governors the electors. Still others favored the state legislatures.

The alternative, and winning, plan, which became known as the Electoral College only some years later, certainly gave the slaveholding states the advantage of the three-fifths clause. But the connection was incidental, and no more of an advantage than if Congress had been named the electors.

Most important, once the possibility of direct popular election of the president was defeated, how much did the slaveholding states rush to support the concept of presidential electors? Not at all. In the initial vote over having electors select the president, the only states voting “nay” were North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia — the three most ardently proslavery states in the convention.

Why?

Slaveholders didn’t embrace the idea of electors because it might enlarge slavery’s power; they feared it because of the danger, as the North Carolina slaveholder Hugh Williamson remarked, that the men chosen as electors would be corruptible “persons not occupied in the high offices of government.” Pro-elite concerns, not proslavery ones, were on their minds — just as, ironically, elite supporters of the Electoral College hoped the body would insulate presidential politics from popular passions.

When it first took shape at the convention, the Electoral College would not have significantly helped the slaveowning states. Under the initial apportionment of the House approved by the framers, the slaveholding states would have held 39 out of 92 electoral votes, or about 42 percent. Based on the 1790 census, about 41 percent of the nation’s total white population lived in those same states, a minuscule difference. Moreover, the convention did not arrive at the formula of combining each state’s House and Senate numbers until very late in its proceedings, and there is no evidence to suggest that slavery had anything to do with it.

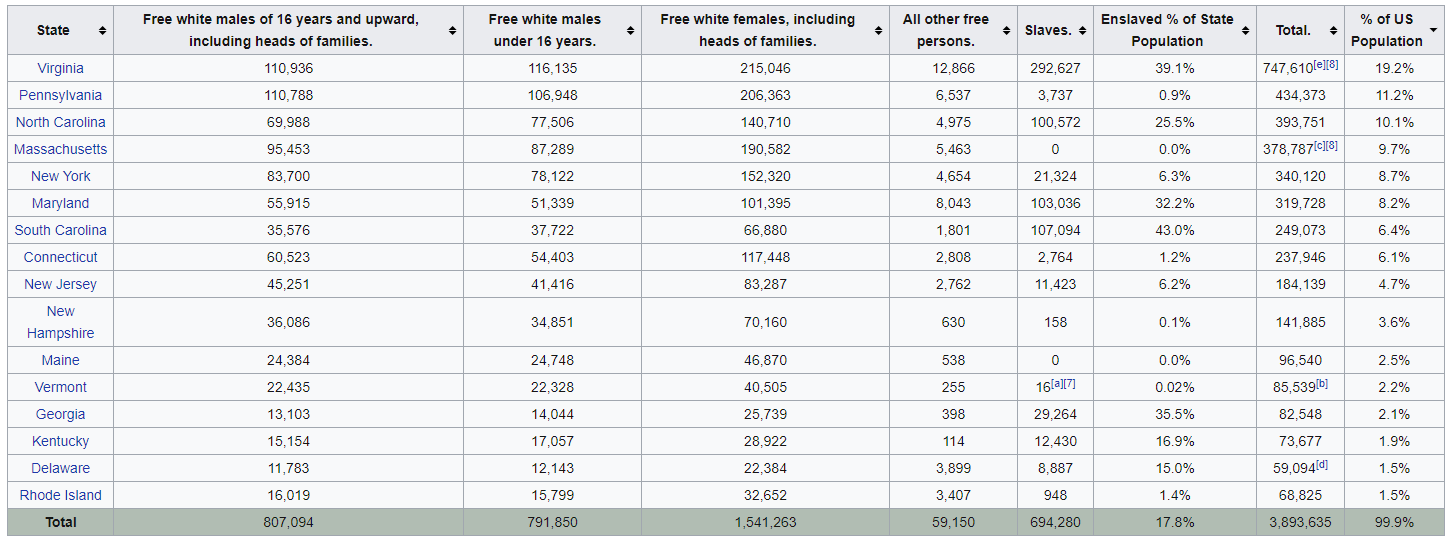

Speaking of the 1790 census, look at the state-by-state data (which I’ve taken the liberty of sorting by overall population):

It’s certainly true that, for example, Virginia and North Carolina become significantly more powerful by virtue of slaves counting 3/5 of a person for the purposes of apportionment. But, by the same token, they’re disadvantaged by the fact that the Senate—and, by extension, the Electoral College—gives outsized power to Rhode Island and other small states. (The numbers are somewhat skewed because Maine which was then part of Massachusetts, and Kentucky, which was then part of Virginia, were tallied separately. Vermont, which was an independent country until 1791, was also counted.)

The other thing the census figures brings home is that “slave state” meant something different at the time the Constitution was drafted than it does in the popular mind today. Most of us—myself certainly included—naturally think of the states that would make up the Confederacy during the Civil War. But all states but two had some slaves and both New York and New Jersey had substantial slave populations.

Of course, the fact that one malign motivation attributed to the Framers was false doesn’t magically transform the Electoral College into a good idea for the modern era. Indeed, the Three-fifths Compromise was rendered moot with the Thirteenth Amendment, anyway, so that particular advantage that former slave states had went away in 1865.

The Electoral College—and, by extension, the Senate—were likely necessary accessions to the small population states in exchange to their consent to move from an unworkable confederation to a more perfect union in 1787/89. But the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution, and other developments have long since rendered us a single nation rather than a collection of sovereign states who joined together for limited purposes. Furthermore, the disparity between the smallest and largest states in terms of population is massively larger than it was at our second founding.

It simply makes no sense to continue to govern ourselves by a set of compromises made for the limited purposes of a completely different country well over two centuries ago. Alas, the process set forth for amendment at that same convention makes it nearly impossible to do otherwise.

I’m a bit confused.

As the number of slaves in, say, South Carolina increased so would the number of SC electors. Right? So the system incentivized slavery with the reward of direct political power. And that additional representation would mean increasingly concentrated power to the slave-drivers of SC. Right? So, the average white South Carolinian had disproportionate power relative to a white person in NY?

How does a white New Yorker achieve parity when a South Carolinian can literally buy more electoral votes by buying humans? The poor New York pol has to run around convincing actual voters while the SC politician can buy his votes, and he has the advantage of using that enhanced power as a cudgel against any internal SC opposition to slavery – losing slavery would mean a loss of power for SC. Right? Or am I missing something?

Imagine the picture for an SC plantation owner. One-man-one-vote means he either has to be limited to the electoral power of whites, or he has to let blacks vote. Either represents a huge loss of power. In my experience people rarely surrender power willingly.

Wilentz says:

So is he now defending the EC on the grounds that it wasn’t put there to protect slavery, as if this historical question is the entire reason on to which to base one’s support or opposition to keeping this institution around today? That strikes me as overly narrow. There are a multitude of reasons for getting rid of the EC that have nothing to do with its history, they have to do with how it functions in the present day. Its role in (possibly) having been created to protect slave states is only relevant insofar as how frequently its defenders invoke a whitewashed, mythological understanding of its origins–the whole “wisdom of the Founders” crap. But it’s hardly necessary to pointing out that the EC is a terrible system.

@Michael Reynolds:

Or blacks get counted as honest to goodness people for purposes of the census, but you use various tricks to ensure that they have no political voice. Then you introduce sharecropping to ensure that they remain economically subjugated. That doesn’t give you the kick of owning slaves, but play your cards right and you might still be calling the shots 200 years after the end of slavery.

The incentive to own slaves for electoral purposes may have been blunted some because they were taxed, so just like any other asset, the law of diminishing returns controls the degree to which slavery will expand. If the extra slaves don’t increase productivity or profit margin, buying them so that the state you live in (rather than you personally) can have additional voting leverage doesn’t pay.

@Michael Reynolds:

I think @Just nutha ignint cracker gets at it: the ROI would be questionable, indeed. It’s the state, not the slave-owner, who gets the vote. And he has to pay twice for the privilege: the cost of buying (and sustaining) the slave and then his part of the increased head tax.

@Kylopod:

Correct. I think it’s just one of several poorly-written sentences in the piece. One presumes Wilentz continues to oppose the EC.

@James Joyner:

I think there are some faulty assumptions in there. The cost of paying for a slave is irrelevant – they were a necessary piece of ‘property’ both to generate wealth and sustain social standing. The ‘head tax’ would be irrelevant when weighed against the horror of one-man-one-vote. It was the equivalent of paying a lobbyist, a necessary expenditure that yielded disproportionate rewards. It was the bone they tossed out so they could eat the steak in peace.

As for it being ‘the state’ not the individual, I don’t think you have a clear picture of the society at the time. South Carolina was owned and operated by a handful of families, all of them major slave owners. There was no line between the individual slave-driver and the state.

And the idea of ROI is quite a recent notion insofar as it can be seen to supersede other concerns. A South Carolina plantation owner was the nobility of his time and place, there was a great deal more at stake than ROI, there was status. We can’t get voters in 2019 to get a clear picture of ROI, why on earth assume that these guys were any better at it? Humans aren’t rational, they don’t make decisions based on simple calculations of profit, it’s much more of an algorithm full of extraneous nonsense like status, religion, ideology, fear, lust, jealousy, all that fun stuff.

What people are good at is calibrating their social status, knowing if they are up or down. The EC acted to give plantation owners more power. People like power. These guys were not blind to the fact that this system gave them power and status.

And again, what was their alternative? One man one vote when SC had a third as many free, white voters as Massachusetts? All the likely alternative formulations were worse for SC and better for MA. They embraced the approach that gave them disproportionate power.

You are thinking about fairness only from the perspective of the people. The equal protection clause didn’t even get added until the 14th Amendment, post Civil War. The bill of rights only protected people from the federal government, not the state governments, etc.

States mattered in the first hundred or so years of our country. Politics were local. People didn’t travel to other states routinely, and they felt loyalty to their state first, and then their country. The sphere o the individual was their state. The Articles of Confederation were even more state centric.

The state was a sovereign entity. It had rights. Far more than today.

Is it fair that if you’ve been living in Virginia your whole life, that people so far away that you’ve never even seen them are making decisions for you, just because there are more of them? If that’s fair, why not just stay in the British Empire? It was less representation, but the end results would be the same — use from afar.

The Civil War crushed states rights. The telegraph, telephone, radio and tv made the huge distances in America matter less and less. You can hop in your car and drive three states away for a weekend. The sphere of the individual is now much larger than their state, and people move from state to state all the time.

States barely matter in people’s lives, compared to what they were.

And now onto my further disjointed rant…

Fifty states is an anachronism. We can now effectively govern much larger regions, and many states seem to cross natural regions (Eastern Washington has nothing to do with Western Washington). Some things are better handled at a very local level, the county/city level, but states are just the wrong level, not local enough, but not large enough to cover the common life of an individual or business.

It’s crazy that if you drive for three hours, you have to handle your weapon differently, free your slaves, or be unable to sell health insurance.

We don’t need two Dakotas. We don’t need two sets of laws for basically identical communities, and the fact the the laws there are basically the same just makes it more annoying.

Our states are like underwear that fits too tightly. They might have been the right size a hundred an fifty years ago, but the individual is much larger now.

@Gustopher:

And the feds now have a large enough budget in order to persuade states to follow its dictates by withholding funding. (That’s as long as the “persuade” doesn’t rise to the level of “coerce” according to the Supreme Court, which has maybe happened once.)

@Michael Reynolds: @Just nutha ignint cracker’s analysis also ignores the ROI that came from the expansion of slave states which increased the value of slaves. The price for a field hand increased so much through the early 19th century, that lower and middle class whites in the South wanted to reopen the Atlantic slave trade. The upper-class whites, who realized this would reduce the value of their “property”, opposed this. The ROI was even better when you consider that one President (Polk) started a war just to expand the number of slave-holding states.

Slavery and its lingering after effects are so ingrained in the culture and history of our country that it is extremely difficult to talk about any portion of American history without referencing it…

This is a bit of a distinction without a difference. The EC itself has lots of factors going into it, however the argument against a popular vote very much involved slavery:

“The remaining mode was an election by the people or rather by the (qualified part of them.) at large. With all its imperfections he liked this best. He would not repeat either the general argumts. for or the objections agst this mode. He would only take notice of two difficulties which he admitted to have weight. The first arose from the disposition in the people to prefer a Citizen of their own State, and the disadvantage this wd. throw on the smaller States. Great as this objection might be he did not think it equal to such as lay agst. every other mode which had been proposed. He thought too that some expedient might be hit upon that would obviate it. The second difficulty arose from the disproportion of (qualified voters) in the N. & S. States, and the disadvantages which this mode would throw on the latter.”

That’s from Madison’s constitutional convention notes. In a popular vote, NY would have had the most sway in choosing the president because they had the most voters.. The EC meant that Virginia would because they had the most people (i.e. slaves). That’s not a trivial thing and was most certainly noted during the convention.

@Michael Reynolds:

The economies not only of the South but of the United States and of Europe relied on slave labor – the industries in the North and in Europe were extremely dependent of cotton produced with slave labor, that would be three times more expensive if it was produced with free workers.

In fact, the problem is that basically every major decision in slave holding societies was about slavery. The people that owned slaves controlled the economy and the political process. The whole economy relied on slave labor. Every major political decision was about protecting slavery. Even policies toward tariffs was influenced by slavery.

Southern society to this day is the same society that was created by slavery.

It’s difficult to argue that a bunch of slave-owners writing a political document were not thinking about slavery when they took a major decision about political power, specially a decision that would benefit states that relied on slave labor.

C’mon.

JJ: I have never seen this kind of data – very good – kudos. Of course we can always argue what it means but it is really great to see it in a chart.

This article from the latest edition of The Economist is behind a paywall, but provides two beefy paragraphs:

@Michael Reynolds: @Console: @Andre Kenji de Sousa: This discussion of Wilentz’ book in the Princetonian is useful:

I would note that the 3/5th Compromise is not, per se, part of the design of the Electoral College (at least not any more than it was part of the design of the House of Representatives).

@Steven L. Taylor:

Agreed. The Electoral College simply reflects the inequities built into the Congress. Most of the objections against it nowadays also apply to the Senate, for example.

@Gustopher:

Actually, states have retained most of their sovereignty, it just doesn’t look that way because the federal government is able to get states to adopt federal policies through other means (mostly money). States can still raise their own military forces but they don’t because it’s not necessary and the feds agreed to pay for most of the National Guard. There are many areas of state law that the federal government and federal courts can’t touch. Many “federal” policies adopted by states could be reversed if states chose to do so. The Federal government, for example, has no authority to dictate drinking ages, speed limits, ID requirements, public benefits and many other things, but states have agreed to change state law in exchange for federal benefits. If that calculus changes (unlikely) then states could opt-out.

In short, states are still the core political unit in this country (a choice intentionally designed into our Constitution) with significant sovereignty, but states have increasingly come to agree with and adopt federal policy for reasons discussed in this thread. That isn’t likely to change, but there’s an important distinction between states adopting federal policy and the feds dictating policy.

@Andy: I would agree that federalism is still important and that there is a a lot of policy still handled by states, such as local law enforcement, K-12 education, and so forth.

States are important and are integral to the system. (But that doesn’t mean there is a good argument for how we elect the president, let alone 2 Senators per state).

Also: even policies that are created by the national government, are implemented by states (e.g., the interstate highway system, food stamps, and a host of other things). This a hallmark of federalism. Federalism means some specific policy autonomy in some areas, and shared responsibility in policy implementation (and even, sometimes, shared funding and policy design) in others.

The mistake a lot of people make (and I am not directing this as anyone in particular) is the notion that federalism means some kind of hard autonomy for state actions (or, really, any true sovereignty–although I understand that the term has some legal relevance in some instances. The practical matter is that no state in the union is truly sovereign).

And to restate something I said above: federalism, as a concept, does not require co-equality of representation in the national legislature (although, conceptually, we would expect a federal system to have some kind of state-based representation in the legislature).

@Steven L. Taylor:

Indeed, other countries with federalist presidential systems (Mexico, Brazil) elect presidents by popular vote. To my knowledge there isn’t anything like the Electoral College outside the US. The argument I often see from EC defenders that it is the only sensible way to handle a national election in a geographically diverse country with lots of states seems based on ignorance of how other countries have operated for ages.

@Kylopod:

Argentina once used an electoral college but, IIRC, its electors were proportionally allocated to its provinces (Argentina is federal).

I think Finland once used an electoral college, but to chose a head of state kind of president (they also have a PM).

The US system is truly unique.

Correct. (But that is true about a lot of people will defend in the US).

@Timothy Watson: Good points on slave trade in general. My comment was exclusively directed at the issue of individuals buying more slaves. Sorry if I caused confusion. I was taking the advantage of increasing the number of states holding large numbers of slaves as a given, but the two phenomena are not identical.

@Steven L. Taylor:

It’s not part of the design of the Electoral College, but both share the same idea of having slaves counted for political purposes but not having them voting by themselves. One could argue that if there was no slavery in the 13 colonies they would not have created the Electoral College.

Half of the colonies were slave-holding colonies in the sense that their economies relied on the plantation, and they had more than half of the population. It’s difficult to argue that slavery was not part of the calculation.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Mexico has at-large senators, so, their Senate is not state-based. I think that’s a wonderful idea.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Exactly. Federalism and confederations are not the same thing.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Sure, there is no complete sovereignty, but states do retain significant sovereignty that isn’t seen in other federal systems. In many areas states do have hard autonomy, they just often don’t exercise it. The shared responsibility in policy implementation, for example, is, in many cases, because of an explicit agreement between the federal government and the states, not because the federal government has complete authority over the states in those areas.

Education is one area. The federal government has no explicit constitutional role in education – it is completely a state affair (limited by the bill of rights, of course). The federal government can only enforce education “mandates” or large parts of title IX because of the nexus of federal dollars. States want the federal dollars so they accept the quid pro quo, but they could choose not to. In other words, a state could, in theory, give up federal education money and ditch many federal mandates, but obviously they don’t want to do that.

The distinction I’m trying to make here is that federal authority gained via restrictions and conditions on the use of federal money is a far different thing than actual federal legal/constitutional control in terms of actual state sovereignty. In education, as is the case in many other areas, states are still sovereign, they’ve just accepted some terms and limits to get access to federal money and they could end that arrangement if they wanted to.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa:

I think can, to a degree, make that argument about the whole constitution. I just don’t think one can make the argument that the 3/5th Compromise is part of the direct design of the EC (and I would if I could, given my known preference to have the EC scrapped).

@Steven L. Taylor:

It’s not part of the direct design of the EC. But these two traits of the EC are related in the sense that they stem from the same idea of counting slaves for political purposes but not having them voting.

Federalist 68 should be mentioned. Hamilton’s explanation and suggestions on rules for the Electoral College.

Nutshell: The Electoral College was the solution for the problems with having the House of Representatives select the POTUS. A separate body of legislators would be created, roughly equal to the number of seats in the House, and those representatives should even be barred from meeting representatives from other states. To preserve slavery? No more than the establishment of the House itself was.

IMO the wisdom of the EC is in the tacit acknowledgement that a single body is highly vulnerable to partisan shenanigans, the naivety is in not realizing that anyone elected for one and only one task is going to be asked one and only one question.

Did not work as envisioned from Day One.

There are two key ingredients missing from this otherwise excellent analysis:

1. Only property owners could vote in the early elections, thus most white men were disenfranchised until the 1828 presidential election. Wealth and class are likely to have been more significant than race in the creation of the system.

2. The problem today isn’t the alleged unfairness of disproportionate weight for small states or lump sum chunks of electors in California, but voter turnout. If you look at the fraction of eligible voters in, say 2012, and multiply by the popular vote (deemed a “true mandate” by opponents of the electoral college), you find that Obama only got a 28% “mandate” in 2012:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voter_turnout_in_the_United_States_presidential_elections#Turnout_statistics

IMO, voter turnout is abysmal because neither party presents a candidate that the electorate feels they can support. Thus, the tiresome “lesser of two evils” meme is perpetually trotted out to buttress a defunct two-party system.

@dazedandconfused: Good point. I’ve read that the Founders expected that most elections would be thrown into the House (Jackson in 1824), and the EC was therefore a compromise or buffer system between direct elections and parliamentary-style selection of the President by the House.

@Martin:

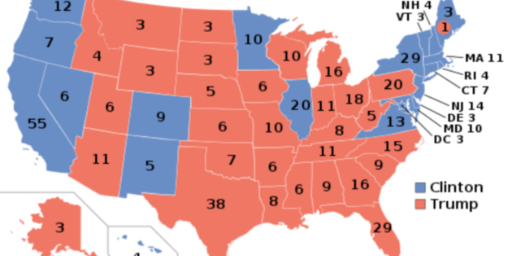

That’s true, and it goes back to the Founders’ failure to anticipate political parties, let alone the two-party system. Electoral deadlocks can in theory happen with just two candidates (here’s a relatively plausible 2020 map that would lead to that outcome), but it’s unlikely. The two elections when a deadlock occurred–1800 and 1824–involved four candidates garnering electoral votes.

Going back to the initial comment (Michael Reynolds): NY wasn’t ideal for his comparison, because that state ranked only 3rd in electoral votes initially (behind PA and VA — see Dr. J’s 1790 population stats). In 1812, NY took the lead in electoral votes for the first time, “reigning” for 150 years until 1968; then the 1970 census gave CA more electoral votes in 1972.

OTOH, SC is a great example because they didn’t even count the popular vote until 1868 (thus one could argue that the civil war freed whites there as well as blacks). Assuming wikipedia’s stats are thorough, states didn’t count popular vote until 1824 and even then several omitted it (and not all were in the south — NY omitted a tally). However, with the white suffrage for non-landowners (part of Michael’s main point about plantation owners) in 1828, fewer states omitted the popular vote tally. If you compare the wikipedia pages for 1824 United States Presidential Election and the one for 1828, you find that the number of ballots cast TRIPLED in Ohio and Pennsylvania, then two of the most populous northern states.

Again, I submit that status, class, and wealth preservation were more significant than race. As an analogy, consider our vaunted “freedom of religion” which was instituted primarily as “freedom to choose your brand of Protestantism”. Recall the founding of PA and RI. Freedom for Catholics, Jews, and others was incidental. Similarly, EC benefits for slavery were incidental IMO.

Gustopher’s second half is worth discussing as a branching topic. In many other countries (e.g., here in Indonesia), the police are national, driver’s licenses are national (issued by local HQ of the national police), and ID cards are national (issued by county government). Some people I’ve spoken with in other countries think it’s bizarre that you have to get a new driver’s license (which is your ID card for most adult Americans) shortly after you move to a different state. OTOH, state or province is a convenient compromise “level” between local and national, especially for infrastructure projects like road construction and maintenance.

@Kylopod:

One of the worst things about the Electoral College is that a tie would not be THAT unlikely. It could be even more chaotic that electing the person with fewer votes.