Pete Buttigieg Lays Out An Encouraging Foreign Policy Platform

South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg laid out his foreign policy platform in a speech this week. It's certainly an improvement over the current President.

Earlier this week South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who has seen his stock rise in the polls at the national and state level for the past two months, became one of the first of the Democratic candidates for President to lay out a foreign policy vision in his first major statement on this policy area since entering the race:

Pete Buttigieg lashed into President Trump on Tuesday for conducting foreign policy by tantrum and by tweet, as he called for the United States to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal, cease the “endless war” in Afghanistan and meet “the clear and present threat” of climate change.

Outlining his foreign policy views as a 2020 Democratic candidate, Mr. Buttigieg, the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Ind., repeatedly invoked the America of 2054 — when he would be Mr. Trump’s age, 72 — in a speech that shared his broad campaign message of generational change.

It seemed aimed at quieting any voters’ qualms about whether he had the experience and maturity to serve as commander in chief, or running the show in the Situation Room, in a race featuring candidates with far more foreign policy experience.

Joseph R. Biden Jr. served eight years as vice president. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey is a member of the Foreign Relations Committee. And Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont has long honed an anti-interventionist message based on his opposition to the Iraq War and to the current war in Yemen.

Mr. Buttigieg, whose political experience is limited to two terms as mayor of a midsize city, also repeatedly invoked his military service to suggest a battle-tested heft on the global stage. He was a Navy Reserve officer deployed in Afghanistan for seven months in 2014, midway through his first term. He described himself as an American forged by 9/11, when “war came to our generation.”

Early in his campaign, Mr. Buttigieg was criticized for introducing himself based on personality, rather than policy, and his address Tuesday, at Indiana University in Bloomington, was his most substantive policy speech to date. Nonetheless, he said, “I do not aspire to deliver a full Buttigieg Doctrine today.”

But he went on to offer prescriptions on a broad range of international issues.

He said the “mission drifted” in Iraq and Afghanistan, at a cost of great “moral authority” to the United States, and he called for Congress to repeal its authorization for the president to wage war in those countries.

“I fear that someday soon we may receive news of the first U.S. casualty of the 9/11 wars who was born after 9/11,” Mr. Buttigieg said.

Throughout the nearly hourlong speech, Mr. Buttigieg launched broadsides at the president, though not by name. Russia, he said, should be viewed “not as a real estate opportunity” but as an adversary that disrupted an American election. On North Korea, he promised, “You will not see me exchanging love letters” with its brutal dictator. China poses far more of a threat than “the export-import balance on dishwashers,” he said, ripping Mr. Trump’s obsession with tariffs and the trade balance.

Mr. Buttigieg drew a picture of a more internationally connected United States than Mr. Trump’s America First policies, which have questioned longstanding security alliances and sought to stem the tide of globalization through tariffs.

//

“Globalization is not going away,” he said.

Alex Ward at Vox has a good summary of the highlights of the speech and, if you wish, you can watch the video here:

While Buttigieg’s background as the Mayor of a modestly sized Midwestern college town does not exactly lend itself to foreign policy experience, Buttigieg does have some claim in his resume for speaking from a position of authority on the subject. Prior to becoming Mayor, Buttigieg served as an intelligence officer in the United States Naval Reserve from 2009 until 2017. As part of that duty, he was deployed to Afghanistan in 2014 and served there for a period of seven months during which he was primarily assigned the task of monitoring and helping to take down terrorist finance networks. Buttigieg did not directly see combat, but he was responsible for escorting superior officers from Bagram Air Force Base to Kabul, a trip that involved passage through territory that was in dispute and in part controlled by anti-government forces. The speech itself lasted more than an hour and is well worth listening to. However, the major takeaways from his specific proposals can be summarized fairly succinctly.

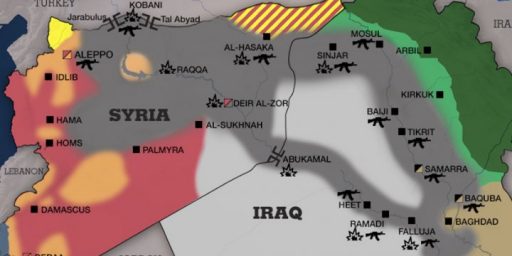

First, Buttigieg called for the rescinding and reconsideration of the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) that was passed in the immediate aftermath of the September 11th attacks. As Buttigieg notes, and as I have argued myself several times, this AUMF has been in place for nearly eighteen years now and has been used by the Bush, Obama, and Trump Administrations as legal justification for missions far beyond the initial war in Afghanistan, which itself has strayed from a counter-terrorist operation to a counter-insurgency operation meant more to prop up the government in Kabul than protect American interests and fight al Qaeda. Indeed, this AUMF is currently being used to justify military attacks that have taken place in Pakistan, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Niger, and other parts of Central, Western, and Eastern Africa. As I have noted, the legal arguments in favor of such an expansive reading of the AUMF are flimsy at best but successive Administrations have failed to seek Congressional consent for this broad interpretation, and Congress has not asserted its own authority in this area.

Borrowing a phrase from Republicans, Buttigieg says he wants to “repeal and replace” the 2001 AUMF with one that narrows the discretion that the original document gave to the President and gives the Congress more of a say in the event that the President wants to expand the authority that it grants. If he actually follows through on this, it would go a long way toward restoring something resembling a balance of the Executive Branch’s authority in the foreign policy area and the ability of Congress to assert its own authority granted under the Constitution.

Second, Buttigieg would recommit the United States to the Joint Comprehensive Plan Of Action (JCPOA), the deal made with Iran in 2015 that for the first time provided for international monitoring of Iran’s nuclear research efforts and largely put a halt to the rush toward a nuclear device that the Islamic Republic had been engaging in. As I have said in the past, this decision by the President was not based in reality and was made despite the fact that both his major intelligence and defense advisers and the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA), which continues to certify Iranian compliance with the terms of the agreement even after the American withdrawal. Given this, getting the United States back into the process is a good idea that every other candidate for President should commit to.

A third proposal is likely to prove to be somewhat controversial with regard to U.S. policy in the Middle East. Specifically, Buttigieg would seek to influence Israeli policy on settlements in the West Bank, which remain a significant roadblock to a peace deal with Palestinians by withholding at least some portion of the aid that the United States sends to Israel if that nation continues to expand settlements into territory that could ultimately end up being subject of peace negotiations. This is likely to prove to be a controversial proposal even among Democrats given the high levels of support for Israel here in the United States.

Fourth, Buttigieg would recommit the United States to the Paris Climate Accords, which President Trump repudiated via Executive Order early in his Presidency. Given the importance of climate change as an issue and the extent to which Trump’s action has damaged America’s relationships with our western allies, this would seem to be a good idea. However, as I have noted in the past, the Paris Accords are largely unenforceable and serve merely as goals and guidelines so the extent to which this would actually accomplish anything is dubious at best.

Buttigieg’s final goal is also related to climate change. Specifically, he is calling for increased investment in renewable energy and other climate-related technologies. While this may or may not be a good idea (the devil, of course, being in the details) I’m not entirely sure what it’s doing in a foreign policy speech.

One other area that Buttigieg addressed, as George Packer summarized in The Atlantic, was China:

Ever since the ’90s, for example, America’s relationship with China has generally been more beneficial for elites than for ordinary Americans. “I’m not among the Democrats who think that China’s nothing to worry about,” Buttigieg said. He might have been talking about Sanders, who barely mentioned China in his two speeches, and then described it not as an economic and political threat but as a global partner on climate change. “While I think it’s a real strategic failure to just poke them in the eye with tariffs and see what happens,” Buttigieg went on, “I think it’s not wrong to perceive a real challenge from China.” Under Trump, he admitted, “there’s something about the orientation on China that I think is not completely wrong.”

But where Trump sees a merely economic rival, Buttigieg sees a dangerous ideological model (“the perfection of dictatorship”) whose stability and success look more and more attractive to other countries. To prevail against that competition, America has to be true to its own claims about itself. “If the U.S. is perceived as seeking to dominate the world as a matter of just calculation around our interests, then I think it’s going to be morally suspect, and it’s going to arouse a lot of resentment around the world and ultimately be self-defeating.” But the rising popularity of Chinese-style authoritarianism and Russian-style oligarchy make it all the more important “that American values be vindicated globally … It’s actually a moment that kind of makes me, more than usual, feel patriotically committed to American values, at least American values at our best and what they’re supposed to be.” In framing a picture of the next few decades as a battle of competing ideologies, Buttigieg sounds a bit like Truman at the beginning of the Cold War.

Buttigieg wants to set a generous narrative of national identity against Trump’s cramped and cruel vision, and against the progressive hostility to any national identity at all. It won’t be easy.

In any case, Daniel Larison, who has been highly critical of President Trump’s foreign policy, had a fairly positive reaction to Buttigieg’s speech:

Buttigieg said some encouraging things about the need for Congress to reclaim its role in matters of war and the need to set a high bar for the use of force abroad. Like many other 2020 candidates, he pledged to take the U.S. back into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and he called for ending our country’s endless wars. These were all good, albeit obvious, positions for any Democratic candidate to take. His position that the U.S. should repeal the 2001 AUMF is a welcome one. His insistence that the U.S. should “replace” it with a new authorization is much less so.

Buttigieg has been fairly criticized for being too reflexively “pro-Israel.” In this speech, he was willing to call out Netanyahu and came out against annexations in the West Bank. It wasn’t as much as he needed to say, but it was a start. He called for criticizing the Saudis for their human rights abuses. He begins talking about it here at 48:00 in the video. I was watching the speech online, and I was expecting him to say more than that about the U.S.-Saudi relationship, but he didn’t. He dispenses with addressing Saudi abuses in less than a minute, and then moves on.

Tellingly, he did not mention the war on Yemen or the Congressional effort to end U.S. involvement in that war. It is a big omission, and all the more so when we consider the important role that many of his 2020 competitors have had in challenging the administration’s despicable Yemen policy. Opposing Trump on Yemen should be a lay-up for a Democratic presidential candidate, and Buttigieg didn’t even try. The omission was all the more noticeable when he kept returning to the theme of defending American values and interests throughout the speech. The debate over the war on Yemen offers a clear example of the need to defend our values and interests against an outrageous policy that tramples on both, but Buttigieg didn’t mention it. That was at best a missed opportunity and at worst a sign that “Mayor Pete” really doesn’t understand that a lot of Democratic politicians and activists believe ending the war on Yemen to be a major priority and a moral imperative.

If Buttigieg was initially one of the candidates least interested in offering policy specifics, he made a serious effort to remedy that with a foreign policy speech that was at least as comprehensive as anything that most candidates in previous cycles have offered much later in the process.

Understandably, much of the rest of Buttigieg’s speech consisted of a series of broadsides at the direction that President Trump has taken American foreign policy since taking office. He was particularly critical, for example, of the extent to which the President has driven a wedge between the United States and our allies, something I’ve written about myself here and here while cozying up to dictators in Russia, China, North Korea, and elsewhere around the globe. He also criticized the extent to which this President has essentially abandoned any concerns about human rights around the globe, thus deviating from a policy course that has been part of American foreign policy since the days of the Cold War. While other Democratic candidates have made mention of these things, Buttigieg is as far as I know among the first to take it on directly.

Even in an hour-long speech, there are still plenty of details about what Buttigieg believes about foreign policy and how he would approach the issues we’re likely to face in the post-Trump world that Buttigieg will need to address in the future. To the extent that this speech is a first step in laying that out on his part, I’d say he did a very good job and that he offers a far more comprehensive and realistic view of America’s role in the world and the current state of the challenges we face than we’ve ever heard from the President. And that gets us to what is likely to be the biggest challenge facing the next President.

Regardless of who succeeds President Trump in either 2021 or 2025, one of their primary tasks is going to be repairing the damage that this President has done to American national interests and our reputation around the globe, something that will only get worse the longer Trump is in office. I’m not sure if Pete Buttigieg is the right person for that job but this speech at least establishes him as a credible speaker on the topic. It will be interesting to see how his rivals for the nomination respond.

A hundred chimps tasked with devising a foreign policy platform by flinging poop at random letters pinned to a board would be an improvement over the current President.

@Mikey:

This is true.

As Mayor of South Bend, he had to deal with the fraught political situation just past his borders in North Bend, and weigh whether to invade to restore democracy and grab the oil.

Seriously, though, does any President go into office with significant foreign policy experience? Poppy Bush might have been the most recent. They typically start out with some vague principles and rely on career civil servants and party members to help apply them, stumbling through the crisis of the day.

We stand a decent chance of electing someone with basically no foreign policy experience at all — Bernie, Warren, or Harris — and it will likely be fine.

It really just matters who they surround themselves with. The pool of Republican foreign policy people is insane (we are very lucky Trump has a strong isolationist streak, which counterbalances those people). The pool of Democrat foreign policy people is… fine.

Americans don’t really vote based on foreign policy. Probably a mistake, but what can you do?

All that said, Buttigieg is startlingly good here.

The value of experience in foreign policy is over-rated. Indeed if the almost unrelieved record of bungling this century is any indication, it’s a positive disadvantage. Someone like Biden, whose instinct will be to keep doing what he’s been doing for the last 50 years, is not what America needs.

My concern about Buttigieg and indeed most of the Democratic Party is the tendency to see China’s rise as a threat. America has enjoyed a unique global hegemony since the end of the Cold War, one that will be impossible to sustain. Trying will bankrupt the nation. The challenge for American political leaders will be to navigate a new multi-polar world as first-among-equals while convincing Americans that other countries catching up does not mean the US is going backwards. Unfortunately Trump has been braying the exact opposite, and there’s little evidence Democrats are willing to call him out.

Climate change is going to affect everything, including, or perhaps especially, foreign policy.

When the more dramatic effects start to take place, we are going to see large human migration/displacement. Water shortages will lead to territory disputes, and famine will be a problem too. There are studies that show–and the U.S. military recognizes–the threat that climate change poses to national security.

Also, what @Mikey: said.