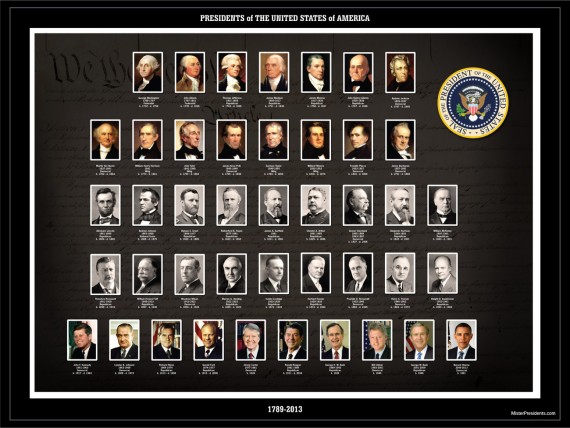

Presidents and Prime Ministers

More on instiutional design.

Apropos of some of the themes I noted in my previous post on institutional design is this book review at Reason: The Presidency Has Turned Into an ‘Elective Monarchy’, a review of The Once and Future King: The Rise of Crown Government in America, by F.H. Buckley.

Apropos of some of the themes I noted in my previous post on institutional design is this book review at Reason: The Presidency Has Turned Into an ‘Elective Monarchy’, a review of The Once and Future King: The Rise of Crown Government in America, by F.H. Buckley.

Judging from the title, I had a negative reaction, insofar as monarchy strikes me as inaccurate for a variety of reasons, but I must confess that the review hits on some vital points (I cannot speak to the quality of the book, as I have not read it and had not even heard of prior to bout 15 minutes prior to typing this).

Those points include two that we make it in our forthcoming book.

First,

Buckley points out, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s “Democracy Index” ranks us as the 19th healthiest democracy in the world, “behind a group of mostly parliamentary countries, and not very far ahead of the ‘flawed democracies.'”

There’s a lesson there, Buckley argues. While “an American is apt to think that his Constitution uniquely protects liberty,” the truth “is almost exactly the reverse.” In a series of regressions using the Freedom House rankings, Buckley finds that “presidentialism is significantly and strongly correlated with less political freedom.”

And, especially second:

That system isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It’s not even what the Framers wanted, Buckley argues. Madison’s Virginia Plan featured an executive chosen by the legislature. The Framers repeatedly rejected the idea of a president elected by the people—that option failed in four separate votes in Philadelphia.

Indeed, it wasn’t just the Virginia Plan that had the legislature picking the executive, but also did other plans considered by the convention: the Pinckney Plan, the Hamilton Plan, and the New Jersey Plan. It was only a late decision by the conventioneers to make the president elected by the electoral college that led to the creation of separation of powers. Indeed, it is worth noting, as I have written on in the past (here and here) and as the review also notes, that even under the electoral college the Framers assumed that the House would normally select the president. In many ways the evolution of the system was not what was intended (which is ironic, given the weight we often given to the intentions of the Framers in our political discourse).

Back to parliamentarism and the main objection to it in the US (as the reviewer does as well):

Still, is there anything that separationism is good for? It stands to reason that the lack of separated powers in parliamentary regimes makes it easier to get big, bad things done.

Buckley acknowledges the point, but counters that it’s also easier to get them undone, and that with a fiscal apocalypse looming, reversibility is more important. That’s a plausible thesis, but I’d have liked to see more actual evidence on how well parliamentary regimes do at repealing bad laws and bad programs.

I think this is a very important point, and I can use recent US politics as an illustration: it took a remarkable moment in time to get Obamacare passed—a few fleeting chances where the Democrats had a 60 vote majority. For a full and total reversal of Obamacare the Republican will need a similar situation with 60 Senate seats. That is not going to happen any time soon.

Another point worth noting:

[presidentialism] insulates the head of government from legislative accountability; and it makes him far harder to remove.

At a minimum this is another chance to point out that institutional design matters and that Americans need to increase their literacy on this topic so that at least intelligent conversation can take place.

But, but, the American Constiutional system of government is the most wonderful system ever devised. The Constitution itself was inscribed on stone tablets and brought to us by the founding fathers who themselves received it from God Almighty on July 4, 1776.

More seriously, it’s time to admit that the founding fathers and their successors made someserious mistakes. But the conservatives who find the myth of perfect origiinal Constiution politically useful will never this or even discuss the history honestly.

Still fight the good fight, Professor. Maybe one day…

Don’t worry libertarians – after Citizens United only politicians that are afraid of redistribution and public spending and in love with the rich and incorporated will become kings anyway. You have no right to whine about details when you’ve already had all the fundamentals stacked in your favor.

Our “balance of powers” makes the most sense in a system like ours in which the head of government and the head of state are the same person.

The real problem we have is that the Congress has abrogated its responsibilities for so long. Despite the head of government and the head of state being resident in the same office ours is not naturally a strong executive system. Except in areas of foreign policy and the military our executive is naturally weak while our Congress is naturally strong.

However, over the period of the last 70 years Congress has increasingly ceded power to the executive. With as large a ship of state as we have changing course would take an enormous amount of effort and I don’t honestly expect it to happen.

We often refer to what goes on in congress as a sausage factory. Let’s be honest the writing of the constitution was the original sausage factory.

Sorry to be cynical, but I wouldn’t count on this happening anytime soon.

Not only are most “free” countries governed by parliamentary systems; paradoxically, many of them are constitutional monarchies. In one list I read a decade ago, the top 10 included: Canada, Australia, the UK, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Perhaps there is a lot to be said for an unelected head of state.

I think the only rich liberal democracies that combine CEO and President in one person are the US and France and both have struggled at addressing essential reforms over the last couple of decades.

It is telling that Germany, Japan, and the ex-Communist countries adopted parliamentary systems when they embraced liberal democracy.

The US Constitution is too much of a theoretical construct; the perfect is the enemy of the good. The Bill of Rights is the truly exceptional American contribution to the social contract.

I agree with Dave Schuler that the abdication of responsibility by Congress since the 1960s has been shocking – all sound and fury and little genuine oversight of the Executive.

And, finally, Congress’s ability to mandate the spending priorities and levels of the Executive, coupled with the ability to refuse to tax to the level necessary to meet those obligations AND the ability to deny the Executive the right to borrow the money to meet those obligations is simply grotesque – a constitutional abomination.

@Dave Schuler:What Dave said.

The most recent example being the end of earmarks. Instead of deciding where the money would be spent, Congress has ceded that authority to the President. And yes, earmarking had it’s problems, mostly the shadowy way in which it was done. The solution was more light on the process, not ending it. Instead, they threw the baby out with the bathwater

So frakin’ what? Are we supposed to be beholden to ideas that have shown themselves to be wrong (or antiquated to modern audiences) just because Madison thought something should be done a different way over two centuries ago? Are Reason and this F.H. Buckley guy going to come out for federal government spending on internal improvements, which Madison supported, anytime soon? Are they going to actively oppose the congressional funding of chaplains, something else that Madison opposed?

Should we also go back to having the state legislatures chose the electors for President?

Should we also go back to allowing a joint caucus of party members in Congress to chose the Presidential nominee?

@Timothy Watson: That wasn’t the point. My point has long been that too many of us revere an institution because it comes from the Framers, but ironically we don’t even understand that is doesn’t work as designed. Indeed, it is an excellent example of how venerating the past is a mistake.

The reason it came up in the book under discussion is twofold (as I understand it): 1. we came extremely close to a parliamentary-like system, and 2. if the EC worked as designed, we would not have the presidency as we understand it.

Again: we venerate something we really don’t understand (and does not work as intended despite all of our claims to want to do what the Framers intended).

Note: I am not saying that we should do whatever was intended. But rather, once we realize that we are not following a Perfect Plan from the Past, we can have a more intelligent conversation on these topics.

I agree with Dave-one huge issue now is that congress doesn’t effectively play it’s role and have handed the president large chunks of their power.

No president is going to refuse more power.

I also think one thing I like in the parliamentary system is the recall. Vote for a certain party but aren’t getting what they promised-then start a recall movement. I sometimes think our system insulates pretty much everyone-and generally because our system favors the legislative incumbent so much once elected that person very possibly has a life time post.

@Steven L. Taylor:

My point was similar.

All the time nowadays, we see people use the following argument: We now do things in x fashion, but Madison (in one of his hundred different proposals or thought experiments) or some other Founder thought we should do things in y fashion, therefore we should do things in y fashion.

Besides the sheer absurdity of that type of argument, it completely ignores the changes in communications, society, etc. that have occurred since 1789.

In part, this also goes back to Montanareddog’s comment and Occam’s Razor: The simplest way to deal with the problem of a too powerful Executive Branch would be to get Congress off its collectives asses and have them do something when the Executive Branch overreaches.

And aren’t conservatives supposed to be all concerned about the intended consequences of governmental action? But now we should get rid of an independent executive just like that? And once this is done, what exactly is supposed to get the legislature in check?

And, to bring up a historical example, are folks ware that it was Parliament, not the King, who the Founders had a problem with originally? The Founders sent a petition to the King seeking his help in mediating the conflict.

I don’t disagree, the people who think we have a “Perfect Plan from God” seem to forget that they needed two Constitutional amendments (XI and XII) just to fix problems with the original Constitution.

@Timothy Watson: Of course, the Colonies’ problem with Parliament was not that it was a parliament, but that they had no representation in said body.

@Just Me:

Well, there have been plenty of presidents who have, as well as most who have stopped themselves from doing things they likely would have gotten away with – like Obama should have done with the War Powers Act during the Libya conflict. That right there was a bigger expansion of presidential power than any single expansion during the Bush period (one of but a few examples where Obama is worse than Bush).

What the founders thought only matters insomuch as people wielding the ability to effect change choose to think it matters. I’m thankful that the nation has evolved a long way from that period in a number of vital areas.

It’s a shame that Boehner isn’t suing in regards to the War Powers Act… it’s pure speculation of course, but I wonder if any part of that has to do with the fact that they hope to be able to wield that power later, when one of their own gets into office. Being people who are constantly finding things to attack Obama for, why they haven’t gone after him on something like this, where they have legal and moral high ground, is perplexing to me… while they focus on things that are small in comparison, and on much shakier footing.

@Centrist Review:

Because they are not acting good faith? A banal political stunt rather than genuine concern for the law? Because the incentives in Congressional elections are now so deformed that they have lost sight of what is their function, and are relentlessly and remorselessly focused on the politics or re-election rather than governance? Because they have repeatedly demonstrated that they don;t give a shit when a Republican is President: whether it is deficits, illegal wars, torture, backroom deals with enemies, soldiers and diplomats dying in service, the use of federal office to target political enemies, executive orders, recess appointments, trials of terrorists in civilian courts, leaking of secrets for political advantage, appointment of grossly incompetent friends as cabinet officers etc.?

@Centrist Review: For decades presidents and congresses have argued over the War Powers Act, yet neither institution (regardless of which party is in control) has been willing to launch a full judicial fight over it.

For that matter, if the legislature was truly serious about protecting its prerogatives in these matters, it could pass further legislation. However, it doesn’t.

Indeed, there has been a clear trend of letting the executive have its way with foreign and military actions. See, for example, the fact that the last declared war was WWII as well as the sweeping Authorization for Use Military Force given to Bush after 9/11 and then in the led up to Iraq.

In other words, the congress, in general (over time, and regardless of partisan control) has been more then willing (when we look at actions, not necessarily rhetoric) to let the president do what he wants in these areas (from Viet Nam to the Balkans to Iraq to Libya and to whatever else you can think of).

It is a systemic problem.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Indeed.

But how does one build momentum for a system overhaul when the system is still functioning as designed in its aspect of change being extraordinarily difficult to make?

It was fascinating to see how a rebellion in a parliamentary system (the UK last year over the use of force in Syria) led the President to decide he was bringing the issue to congress as he should have done from the start. This led to wholesale panic in both the Executive (that the vote may be lost) and in Congress (that they would be caught between the activist foreign policy consensus of the elite and massive opposition in the electorate). Only the Russian Foreign Minister (inadvertently) got them out of the jam.

For me, this shows that the President could, if he wanted, return some responsibility (not power – the problem at the moment is Congress has power and not responsibility) to Congress and to make them share ownership of certain policies.

I don’t believe the argument that gerrymandering has led Reps to be less representative of their constituents than before. is the whole story. There were 30 Conservative MPs who voted against the Government in that marvelous moment for Parliamentary oversight; I bet plenty of them were in safe Tory seats.

Anyway, currently the President only has leverage in the Senate’s order of business – but he should use it more often in such cases.