Progress towards Peace in Colombia

The FARC have disarmed. Now to the hard part.

From earlier this week in the NYT: ’Goodbye, Weapons!’ FARC Disarmament in Colombia Signals New Era

From earlier this week in the NYT: ’Goodbye, Weapons!’ FARC Disarmament in Colombia Signals New Era

The rebels have abandoned their battle camps for demobilization camps like the one in a lush stretch of countryside near Mesetas — temporary settlements of tents and drywall buildings where the rebels have been slowly handing over their weapons, 7,132 at last count.

Some rifles will remain at the camps for security purposes until Aug. 1, the United Nations inspectors said, and rebel weapons caches were still being examined. But for the most part, the inspectors said, the disarmament is essentially complete.

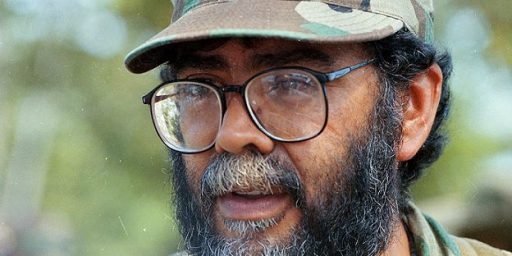

This is truly a remarkable milestone. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia have been fighting in the countryside since the mid-1960s. There have been numerous attempts to negotiate peace terms, including major talks in the mid-1980s and the late-199os/early 2000s. While there still remains one significant rebel group still active, the ELN (National Liberation Army), it does appear that Colombia is entering a new era in which it no longer faces ongoing guerrilla war. Of the two groups, the FARC has been the most active this century (and there is a peace process underway with the ELN, which was spurred on in part by the process with the FARC).

Getting the FARC out of the field seemed, for some time, to be impossible. While other groups abandoned armed struggle decades ago, the FARC seemed unmovable. The combination of the absence of state presence in significant parts of Colombia, right-wing violence against the left, and funding from the cocaine trade all created a context in which peaceful demobilization continued to be untenable. A combination of military success against the group and increased political will changed that calculation and we are finally at the true demobilization and disarmament stage. (For a backgrounder on the war with the FARC that elaborates on these points, see my Origins piece from last year: Colombia: On the Brink of Peace with the FARC?).

As difficult as it has been to get this point in Colombian history, arguably the hard part remains.

“The goal of ending the war has essentially been met,” said Cynthia J. Arnson, the director of the Latin America program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “It’s implementing the 300-plus-page document, with 100 different programs and strategies, that’s going to be difficult.”

There are numerous challenges with implementation of this plan, not the least of which being the integration of thousands of former fighters into civil society and the economy. This is especially true when one considers that the reason many joined the guerrillas in the first place was the lack of state presence in much of Colombia’s national territory and the lack of economic opportunities commensurate with those state deficiencies. A major concern will be the personal safety of these persons, especially those who remain politically or socially active. There remains a real threat from right-wing violence. Indeed, the slaughter of left-wing politicians during the peace attempts of the 1980s remains the basis of real fear:

Like many of the rebels, Ms. López is afraid of what might happen now that the former guerrillas must depend on the state for protection. She mentioned the last time the FARC experimented with political participation, running candidates for office under the Patriotic Union party banner, only to face massacres by right-wing paramilitary groups that the government failed to stop. Those groups still exist.

“They could kill us one by one,” Ms. López said.

An immediate challenge will be the transformation of the FARC into a viable political party. The peace accords guarantees such a party a minimum of five seats in the Chamber and Senate for the 2018 and 2022 cycles, as well as technical support. While on the one hand, such a party ought to have real support in certain portions of the country, the track record for Colombia’s electoral left has not been stellar over the years. It is highly unlikely such a party will ever have large success. However, for the peace to be successful, I think that it is important that such a party be able to establish a level of stable representation over time so as to demonstrate that there is a viable, non-violent, democratic route to voice in government for segments of the population that have long felt ignored or forgotten by Bogotá.

As such, I will echo President Santos:

“This is the best news for Colombia in 50 years — this is great news of peace,” he said, adding that the country could now finally unify as a democracy. “Today we see the end of this absurd war.”

I have been studying Colombia since early in my graduate school career, first traveling to the country in 1992 as a first step towards writing my doctoral dissertation on the country’s constitutional reform as it pertained to its electoral system. I have subsequently lived a year in Colombia, written a book about its electoral process, and authored numerous papers, chapters, articles, and such on the subject. All of which is to point out that I have a basis in saying that this truly is a remarkable and monumental time for the country. It is also one that remains tenuous and success is not fully guaranteed. Violence is not over, even if is it much improved. Criminality persists (the drug trade will, for example, continue). Still, I do think an era is ending. Armed political struggle, an artifact in many ways of the Cold War,* is finally over in Colombia (recognizing that that ELN’s disposition remains an issue).

—

*Although, the FARC has been in operation as much, if not more, in a post-Cold War world than it did in the Cold War one, depending on when one wants to date those eras.

I’m curious about the drug trade. Do you think the areas with little or no government influence will become fiefdoms essentially controlled by cartels as in some parts of Mexico?

@Mr. Prosser: I think that we will certainly see localized criminality have a great deal of influence in various areas of the country–although I wouldn’t think of them as fiefdoms (I don’t think that applies to Mexico, either, to be honest). I will say that Colombia lacks the large, identifiable crime organization that Mexico has–that is a thing of the past.

The real threat is going to be twofold: coca cultivation and cocaine trafficking are still going to fuel crime and violence, and right-wing paramilitary groups linked to local politicians will use violence to stop integration of what they will see as left-wing agitators into local politics.

It is worth noting that coca cultivation is up. (And as long as people want to snort the white powder, people are going to grow those leaves).

*kudos* for this piece.

I left my country some five years ago, therefore I could not witness up close the whole process.

From what relatives and friends tend to comment the people in Colombia are both hopeful about the end of this conflict but also fear that the integration process won’t be successful.

I am at the moment celebrating the end of this era.

@Just another interested outsider….: Thanks. And yes, that is the same sense I get from my Colombian friends.