Punishment for Acquitted Conduct

The Supreme Court may revisit a controversial criminal justice ruling.

YahooNews points me to an AP story from earlier in the week: “Supreme Court asked to bar punishment for acquitted conduct“

A jury convicted Dayonta McClinton of robbing a CVS pharmacy but acquitted him of murder. A judge gave McClinton an extra 13 years in prison for the killing anyway.

In courtrooms across America, defendants get additional prison time for crimes that juries found they didn’t commit.

The Supreme Court is being asked, again, to put an end to the practice. It’s possible that the newest member of the court and a former federal public defender, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, could hold a pivotal vote.

McClinton’s case and three others just like it are scheduled to be discussed when the justices next meet in private on Jan. 6.

Sentencing a defendant for what’s called “acquitted conduct” has gone on for years, based on a Supreme Court decision from the late 1990s. And the justices have turned down numerous appeals asking them to declare that the Constitution forbids it.

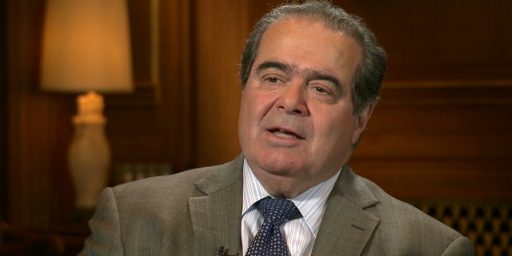

The closest the court came to taking up the issue was in 2014, when Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg provided three of the four votes necessary to hear an appeal.

“This has gone on long enough,” Scalia wrote in dissent from the court’s decision to reject an appeal from defendants who received longer prison terms for conspiring to distribute cocaine after jurors acquitted them of conspiracy charges.

Scalia and Ginsburg have since died, and Thomas remains on the court. But two other justices, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, have voiced concerns while serving as appeals court judges. “Allowing judges to rely on acquitted or uncharged conduct to impose higher sentences than they otherwise would impose seems a dubious infringement of the rights to due process and to a jury trial,” Kavanaugh wrote in 2015.

Jackson, who also previously served on the U.S. Sentencing Commission, could provide a fourth vote to take up the issue, said Douglas Berman, an expert on sentencing at the Ohio State University law school.

“She is someone who we’d have good reason to believe would be troubled by the continued use of acquitted conduct,” said Berman, who filed a brief calling on the court to take up McClinton’s case.

Jackson replaced Justice Stephen Breyer, who generally favored giving judges discretion in imposing prison terms. Reining in the use of acquitted conduct in sentencing would restrict judicial discretion.

Despite the increasing polarization on the Supreme Court along party lines, it’s interesting that Scalia, Thomas, and Ginsburg were in alignment on this in the minority. At first blush, punishing someone for a crime he’s been acquitted of is simply outrageous. Even Scalia and Thomas see that.

The reality is more complicated.

McClinton, then 17, was part of an armed group that robbed a CVS pharmacy in Indianapolis in 2015 in search of prescription medicines, including opioids. The take was meager, about $68 worth of drugs, McClinton’s lawyers said in court papers. After one member of the group refused to share the proceeds, he was fatally shot in the back of the head at close range.

The reputed leader and other members of the group testified against McClinton at trial, as part of their bid for reduced prison terms, McClinton’s lawyers wrote.

Even with the testimony, jurors acquitted McClinton of the most serious charges against him. He should have faced six years in prison, at most.

Instead, the trial judge gave McClinton 19 years, finding that it was more likely than not that McClinton was responsible for the killing. The legal standard in a jury trial is higher, proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Upholding McClinton’s prison term, Judge Ilana Rovner wrote for a unanimous three-judge panel of the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that lower-court judges are bound by a 1997 Supreme Court ruling that “a jury’s verdict of acquittal does not prevent the sentencing court from considering conduct underlying the acquitted charge, so long as that conduct has been proved by a preponderance of the evidence.”

But Rovner noted that a growing number of federal judges “have questioned the fairness and constitutionality of allowing courts to factor acquitted conduct into sentencing calculations.”

McClinton committed an armed robbery—the fact that they didn’t come away with a lot is entirely irrelevant—and subsequently likely killed a co-perpetrator in that crime. His co-conspirators testified to that fact. Surely, that’s a fact that should be taken into account in sentencing?

The 1997 case in question, United States v. Watts (decided along with a companion case, United States v. Putra) is summarized thusly:

Respondent Watts was convicted of possessing cocaine base with intent to distribute, but acquitted of using a firearm in relation to a drug offense. Despite this, the District Court found by a preponderance of the evidence that Watts possessed guns in connection with the drug offense, and therefore added two points to his base offense level when calculating his sentence under the United States Sentencing Guidelines. In a separate case, respondent Putra was convicted of aiding and abetting possession with intent to distribute cocaine on May 8, 1992, but acquitted of aiding and abetting such a transaction on May 9. Finding by a preponderance of the evidence that she had been involved in the May 9 transaction, the District Court calculated her Guidelines’ base offense level by aggregating the amounts of both sales. In each of these cases, the Ninth Circuit held that the sentencing courts could not consider respondents’ conduct underlying the charges of which they had been acquitted.

The majority held:

A jury’s verdict of acquittal does not prevent a sentencing court from considering conduct underlying the acquitted charge, so long as that conduct has been proved by a preponderance of the evidence. The Ninth Circuit’s contrary holdings conflict with the clear implications of 18 U. S. C. § 3661, the Guidelines, and this Court’s double jeopardy decisions, particularly Witte v. United States, 515 U. S. 389. Section 3661 codifies the longstanding principle that sentencing courts have broad discretion to consider various kinds of information, including facts related to charges of which the defendant has been acquitted. Further, this Court has held that consideration of information about a defendant’s character and conduct at sentencing does not result in punishment for any offense other than the crime of conviction. Id., at 401. In addition, acquittal merely proves, not that the defendant is innocent, but the existence of a reasonable doubt as to his guilt. Thus, an acquittal does not preclude the Government from relitigating an issue in a subsequent action governed by a lower standard of proof. Dowling v. United States, 493 U. S. 342, 349. The acquittals below shed no light on whether a preponderance of the evidence either established Putra’s participation in the May 9 sale or Watts’ use of a firearm in connection with a drug offense.

The opinion was issued Per Curiam, rather than signed by its author, because it was relatively short and essentially just reiterated established opinion.

Scanning the opinion, much of it is based on statutory interpretation of the sentencing guidelines passed by Congress but also touches on Constitutional interpretation:

The Court of Appeals’ position to the contrary not only conflicts with the implications of the Guidelines, but it also seems to be based on erroneous views of our double jeopardy jurisprudence. The Court of Appeals asserted that, when a sentencing court considers facts underlying a charge on which the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, the defendant “‘suffer[s] punishment for a criminal charge for which he or she was acquitted.’ ” Watts, 67 F. 3d, at 797 (quoting Brady, 928 F. 2d, at 851). As we explained in Witte, however, sentencing enhancements do not punish a defendant for crimes of which he was not convicted, but rather increase his sentence because of the manner in which he committed the crime of conviction. 515 U. S., at 402-403. In Witte, we held that a sentencing court could, consistent with the Double Jeopardy Clause, consider uncharged cocaine importation in imposing a sentence on marijuana charges that was within the statutory range, without precluding the defendant’s subsequent prosecution for the cocaine offense. We concluded that “consideration of information about the defendant’s character and conduct at sentencing does not result in ‘punishment’ for any offense other than the one of which the defendant was convicted.” Id., at 401. Rather, the defendant is “punished only for the fact that the present offense was carried out in a manner that warrants increased punishment …. ” Id., at 403; see also Nichols, 511 U. S., at 747.

The Court of Appeals likewise misunderstood the preclusive effect of an acquittal, when it asserted that a jury” ‘reject[sJ”’ some facts when it returns a general verdict of not guilty. Putra, 78 F. 3d, at 1389 (quoting Brady, supra, at 851). The Court of Appeals failed to appreciate the significance of the different standards of proof that govern at trial and sentencing. We have explained that “acquittal on criminal charges does not prove that the defendant is innocent; it merely proves the existence of a reasonable doubt as to his guilt.” United States v. One Assortment of 89 Firearms, 465 U. S. 354, 361 (1984). As then-Chief Judge Wallace pointed out in his dissent in Putra, it is impossible to know exactly why a jury found a defendant not guilty on a certain charge.

I’m queasy about this but it makes good sense. The whole point of having a judge in charge of sentencing is that they’re supposed to apply, well, judgment. They really have to trusted to take the totality of circumstances into consideration.

That a jury rules that there is reasonable doubt as to whether a defendant committed a murder should absolutely mean they can’t be punished for the murder. But that hasn’t historically meant the judge can’t take into account that it’s more likely than not he actually committed the murder into sentencing. That’s no more double jeopardy than a killer being acquitted in a criminal trial and then found liable in a civil trial based on the same circumstances.*

It’s noteworthy that Scalia and Beyer concurred in the judgment, merely putting their two cents in on the powers of the Sentencing Commission under law.

Breyer:

I join the Court’s per curiam opinion while noting that it poses no obstacle to the Sentencing Commission itself deciding whether or not to enhance a sentence on the basis of conduct that a sentencing judge concludes did take place, but in respect to which a jury acquitted the defendant.

In telling judges in ordinary cases to consider “all acts and omissions … that were part of the same course of conduct or common scheme or plan as the offense of conviction,” United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual § lB1.3(a)(2) (Nov. 1995) (USSG), the Guidelines recognize the fact that before their creation sentencing judges often took account, not only of the precise conduct that made up the offense of conviction, but of certain related conduct as well. And I agree with the Court that the Guidelines, as presently written, do not make an exception for related conduct that was the basis for a different charge of which a jury acquitted that defendant. To that extent, the Guidelines’ policy rests upon the logical possibility that a sentencing judge and a jury, applying different evidentiary standards, could reach different factual conclusions.

This truth of logic, however, is not the only pertinent policy consideration. The Commission in the past has considered whether the Guidelines should contain a specific exception to their ordinary “relevant conduct” rules that would instruct the sentencing judge not to base a sentence enhancement upon acquitted conduct. United States Sentencing Commission, Sentencing Guidelines for United States Courts, 57 Fed. Reg. 62832 (1992) (proposed USSG § 1B1.3(c)). Given the role that juries and acquittals play in our system, the Commission could decide to revisit this matter in the future. For this reason, I think it important to specify that, as far as today’s decision is concerned, the power to accept or reject such a proposal remains in the Commission’s hands.

Scalia disagrees:

I do not agree with the assertion in JUSTICE BREYER’S concurrence that there is no obstacle to the Sentencing Commission’s reversing today’s outcome by mandating disregard of the information we today hold it proper to consider. Title 28 U. S. C. § 994(b)(1) requires the Guidelines to be “consistent with all pertinent provisions of title 18, United States Code.” In turn, 18 U. S. C. § 3661 provides that “[n]o limitation shall be placed on the information concerning the background, character, and conduct of a person convicted of an offense which a court of the United States may receive and consider for the purpose of imposing an appropriate sentence.” In my view, neither the Commission nor the courts have authority to decree that information which would otherwise justify enhancement of sentence or upward departure from the Guidelines may not be considered for that purpose (or may be considered only after passing some higher standard of probative worth than the Constitution and laws require) if it pertains to acquitted conduct. If the Commission believes that the rules of evidence and proof established by the Constitution and laws are inadequate, it may of course recommend changes to the Congress, cf. 28 U. S. C. § 994(w).

Justices Stevens and Kennedy, both of whom have retired (replaced by Kagan and Kavanaugh, respectively), are the lone dissenters.

________________

*I have different problems with that, owing to the financial and other burdens imposed and the concomitant potential for abuse. But that’s a digression from the matter at hand.

I would argue that the sentencing matters far more to a convicted defendant than does the conviction itself. Thus, adding time for crimes that the defendant (in the eyes of the court) literally did not commit would be blatantly cruel and unusual punishment.

I’m surprised this practice has withstood any level of scrutiny at all, but then we Americans often see only “punishment” as appropriate remediation for all manner of societal misdeeds.

My first reaction is a question. IANAL My understanding is that very few criminal cases go to trial, but are decided by plea bargain. If judges can ignore a jury decision can they ignore plea bargains? Once a bargain has been accepted, can the judge base sentencing on charges the prosecutor dropped in bargaining and on which the defendant did not plead guilty?

The only fact I can find in the above is that his “co-conspirators testified” against him. In exchange for more lenient sentences. Maybe he did, maybe he didn’t, but the jurors did not find their testimony to be credible and I have no reason to 2nd guess them.

Who needs a jury when our judges are omniscient? We should just remove the whole “jury of our peers” from the constitution as it just gets in the way of prosecutors and judges giving the miscreants in our society what they so richly deserve.

Good morning, Dr. Joyner. How would you say Michele Fiore’s appointment in Nevada factors into your opinion?

@OzarkHillbilly:

Which we have largely done. See my comment above asking if this same “judicial supremacy” principle applies to plea bargains.

@OzarkHillbilly:

Morning, Ozark. Yes, a judge can reject a plea deal.

@gVOR08: IANAL either, but my understanding is that the judge has to accept the plea bargain for it to stand. Almost all are accepted; the judges know that the criminal trial system is tottering along only because 90% or more of the cases are settled by bargain. If all cases had to be tried, the whole thing would collapse as people were either jailed (or allowed to run loose) for many years before they had to be in court.

Let’s say you’re tried for a crime, any crime, and are acquitted of al charges. If the judge thinks there’s a preponderance of evidence that you’re guilty anyway, can they sentence you to a prison term on that basis?

I’m sure the answer is no.

That’s the right answer, and it’s still the right answer if convicted of some charges but acquitted of others.

I’m going to have to get my b.p. under control before I respond beyond Arrrrggghhh!

ETA, IANAL either, but from what I’ve seen in state courts, judge can accept plea bargains but set sentence beyond standard. One reason it’s called ‘getting bitched’ inside the walls.

Arrrrggghhh!!!

I see Ms Lake down there in AZ has deleted some social media thing claiming terrible things about the judge in her case. Hmmm

On plea bargains, my understanding is the judge accepts or rejects the deal before it’s formally entered.

@gVOR08:

Yes. Judges generally go along with negotiated plea agreements, but they are not required to do so. A judge can choose to reject the agreement and impose sentencing that he/she feels is appropriate.

@OzarkHillbilly:

It’s important to remember that judges, not juries, determine and impose sentencing (with pretty much the sole exception of capital punishment, and even there caveats and exceptions exist). Juries, where they are employed, determine innocence / guilt. They may recommend sentencing in jurisdictions where the rules of procedure permit them to do so, those are recommendations. Sentencing guidelines are just that – guidelines.

It’s also important to keep in mind that McClinton was never acquitted of murder. Indeed, he was never charged with murder. He was charged with robbery of the pharmacy; brandishing a firearm during the pharmacy robbery; robbery of Perry; and using a firearm during and in relation to the robbery of Perry, causing death. Convicted of the first two, acquitted on the second two. Homicide was never on the menu for the jury to consider.

The argument became, and I agree, that the proximate criminal act was the robbery of the pharmacy, in which all parties were involved. McClinton’s actions with regard to Perry can be, and IMLO should be, considered ongoing components of the original criminal act – the robbery of the pharmacy (for which McClinton was convicted). But for the original robbery, Perry would arguably still be alive. What followed with regard to sentencing is quite defensible.

Small note: Stevens was succeeded by Kagan, not Jackson. Jackson succeeded Breyer.

@DeD: OK, but seeing as I said nothing about plea bargains it’s kinda besides my point. You are perhaps replying to @gVOR08: ?

@HarvardLaw92: Agree to disagree. My argument is basically, “sometimes the law is an ass.”

@OzarkHillbilly:

Indeed, I was. My bad.

@OzarkHillbilly:

I think it might be more “but that’s not fair!” and I respect that. Consider this – distributing the proceeds of a robbery is an ongoing component of that robbery, even if they take place in different locations. What likely happened here is not that there was no evidence that McClinton killed Perry. It’s far more likely a case of the jury felt that there wasn’t enough evidence to substantiate that McClinton robbed Perry, and that is what he was actually charged with. If the robbery goes out the window, the use of a firearm in a robbery has to go out the window as well. Is it fair that McClinton effectively gets away with murder because they couldn’t convince a jury of robbery?

What happened here was nothing more than a sentencing enhancement, if we’re honest about it.

@HarvardLaw92: The prosecutor had the option of bringing those charges, and decided not to – possibly because there was insufficient evidence, possibly other reasons.

To effectively punish a person for a crime for which they were not charged, nor convicted, in this case “murder”, strikes me as wholly unfair.

@HarvardLaw92:

I can’t square the circle of how the jury acquitted him of murder, as reported, and your assertion he was never charged with murder. Just for S&Gs, here’s an account of the case from the HLR.

He must have been charged with murder for the jury to have acquitted him of it, right?

@dazedandconfused:

The reporting is in error. Look at the 4th paragraph of your source.

@Tony W:

I don’t disagree that the charging was flawed, although I understand why they went that route (one extended criminal act). As I said though, this was effectively a sentencing enhancement for the crimes for which he was convicted, not an added punishment for acts with which he was never charged.

@HarvardLaw92:

Yes, but in terms of understanding, “…using a firearm during and in relation to the robbery, causing death” and “homicide” are distinctions without significant difference. He was charged with killing someone.

@HarvardLaw92: Yes, fixed. There’s a “Steven” involved either way!

@HarvardLaw92: The HLR op-ed @dazedandconfused links definitely does a better job than the news reports of summarizing the sequence of events—and makes me less queasy about the result here.

@HarvardLaw92: It feels like the prosecutor now gets two bites at the apple here if they so choose.

They can now charge the dude with murder and create a situation where he is serving time twice for the same crime.

@dazedandconfused:

He actually wasn’t.

@Tony W:

They actually can’t. Jeopardy attached due to the nature of the acquitted charge. They went after the sentencing enhancement so vigorously precisely because they don’t have another bite at the apple.

What CAN happen is that McClinton can still be tried and possibly convicted for the murder at the state level.

@HarvardLaw92: ” Is it fair that McClinton effectively gets away with murder because they couldn’t convince a jury of robbery?”

Isn’t “convincing a jury” the entire basis of our system of justice?

The argument here seems to be something like “better a thousand innocent people be sent to jail than one person a judge decides is guilty goes free.”

@wr:

You’re free, of course, to be verklempt. I’m fine with this one. Justice was done.