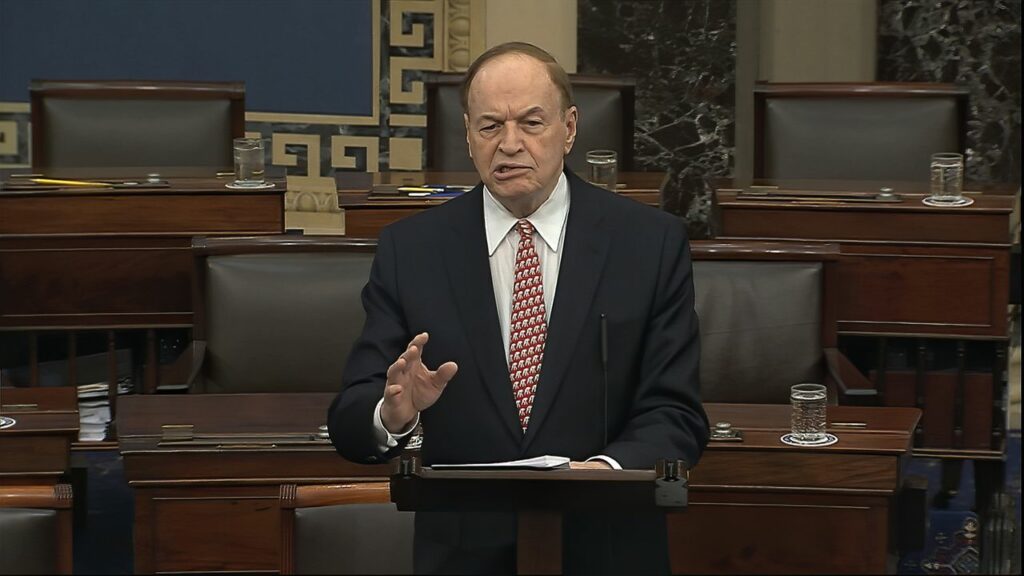

Richard Shelby and the Old Senate

"You can't be against everything."

Richard Shelby, the 88-year-old who has represented my erstwhile home state of Alabama in the U.S. Senate longer than any other person, declined to run for re-election and is retiring next week. Floods of roundups of his long and complicated career have poured out.

NYT (“Shelby, One of the Senate’s Last Big Spenders, ‘Got Everything’ for Alabama“):

For the first time in years, there are signs of dramatic transformation on the banks of the Mobile River. The waterway is dug wider and deeper by the day. Mobile’s airport will soon move in. And sitting watch from the waterfront is a three-foot bronze bust of the man who brought home the money to finance it: Senator Richard C. Shelby.

Determined to the point of obsession to harness the potential of Alabama’s only seaport, Mr. Shelby, who has served in Congress for more than four decades, has used his perch on the powerful committee that controls federal spending to bring in more than $1 billion to modernize the city’s harbor, procuring funding for projects including new wharves and better railways. The result is one of the fastest-growing ports of its kind, which today contributes to one in seven jobs in the state.

It is also something of a monument to a waning way of doing business on Capitol Hill, one that has fueled many a bipartisan deal — including the $1.7 trillion spending bill that cleared Congress last week, averting a government shutdown — and whose demise has contributed to the dysfunction and paralysis that has gripped Congress in recent years.

Mr. Shelby, who is retiring at 88, is one of the last of the big-time pork barrel legends who managed to sustain the flow of money to his state even as anti-spending fervor gripped his party during the rise of the Tea Party and never quite let go.

The Alabama senator did not just use his seat on the Appropriations Committee to turn the expanding port into an economic engine. Applying his influence, seniority, craftiness and deep knowledge of the arcane and secretive congressional spending process, he single-handedly transformed the landscape of his home state, harnessing billions of federal dollars to conjure the creation and expansion of university buildings and research programs, airports and seaports, and military and space facilities.

Roll Call (“Once again, Shelby stands alone when it comes to earmarks“):

Call him the billion-dollar man.

Make that $1.2 billion, to be precise, which is the total earmark haul that departing Senate Appropriations ranking member Richard C. Shelby could bring home during the 117th Congress — the last of the Alabama Republican’s congressional career dating back to 1979.

Shelby is clearly going out at the top of the charts for the second year in a row after lawmakers restored the once-reviled practice of parking federal funds in their own constituents’ backyards. He procured a devilishly large $666 million in the fiscal 2023 omnibus package, according to a CQ Roll Call analysis, after roughly $550 million the previous fiscal year.

Shelby’s total even grew slightly from the earlier round of Senate-introduced bills in July. He added $10 million in the final package that wasn’t included previously for the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa to create “an institute on public service and leadership, including a scholar’s program.”

Last year, Shelby announced that upon his departure from Washington he planned to donate his official Senate papers, records and materials to the university.

Shelby’s papers would be a “catalyst for The University of Alabama to consider the creation of a new institute and new academic, leadership and scholarly research programs that would provide students, faculty and staff with opportunities to engage with prominent politicians and policy professionals,” school officials said in a release.

POLITICO (“Shelby’s swan song: A spending spat within his party“):

Richard Shelby is leaving the Senate after 36 years with arrows lodged in his back — by his own party.

Shelby is coming under heavy fire from conservatives for cutting one last deal with Democrats on a massive year-end spending bill, an effort supported by both Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and President Joe Biden. Yet the Alabamian’s fellow Republicans are calling him a fiscal sellout for trying to fund the government for much of next year before a chaotic GOP House takes over in January.

[…]

Asked if he’s happy to take the heat for a deal that will divide his party painfully, Shelby replied: “Happy is a nebulous term.” For the most part, though, the 88-year-old senator is taking it in stride, arguing his critics do little good by resisting everything.“The Republican leader in the House [Kevin McCarthy], he’s focused on one thing: being speaker,” Shelby told POLITICO last week during an hour-long interview in his office. “That’s part of the political game.”

He even thinks his work will help save the House GOP majority from itself next year, staving off months of bitter infighting over federal spending bills. Not that Shelby expects a gift basket from McCarthy and his allies.

“If we’re successful, we’ll have probably done them a favor,” Shelby said. “There probably won’t be much thanks for it.”

But “they can’t say that,” Shelby added. “I understand what they’re doing and why they’re doing it.”

[…]

It’s a fitting end to his almost four decades in Congress, with nearly the last five years spent as the GOP’s chief appropriator. After succeeding the late Republican senator from Mississippi, Thad Cochran, Shelby similarly lavished his state with federal largesse, from the Port of Mobile to the state’s university. But Shelby insisted that his critics are wrong about his motivations.

Reminded of Roy’s comment, Shelby countered: “I don’t want a monument. Monuments are for pigeons and dogs.”

[…]

Shelby’s role taking the heat from his party “goes with the business. You know, like being a head coach,” said Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.). When asked whether Shelby’s work helps Republicans avoid trouble next year, Tuberville answered unequivocally: “Yes.”

It’s ancient history now, but Shelby’s career arc is newly relevant in the wake of Sen. Kyrsten Sinema’s (I-Ariz.) decision to ditch the Democratic Party. Shelby was first elected to the Senate in 1986 as a Democrat, joining the Republican Party in 1994.

During a breakfast at the White House as a relatively new congressman in 1981, Shelby recalled, then-President Ronald Reagan and then-Vice President George H. W. Bush tried to convince him to switch parties. At the time, Shelby thought he was fairly “progressive.”

So Shelby stayed with the Democrats and even toyed with the idea of leaving office. Yet by the time he made the switch 13 years after that meal, he had earned a reputation for cozying up to the GOP and often voting with Republicans. In 1993, Shelby criticized then-President Bill Clinton’s budget with three words that Republicans still use today: “The taxman cometh.”

After serving as both a Democrat and a Republican, Shelby said he learned that “you’re not going to have your way yourself. You’ve got to work with other people to advance your cause. Try to understand where they’re coming from.”

It just so happens that Shelby’s former chief of staff, Katie Britt, is taking his place as Alabama’s next Republican senator. Britt defeated Republican Rep. Mo Brooks in a runoff earlier this year. Shelby directed his own political funds to help Britt get elected and “did everything I could to help her … but she did a lot on her own, though. She’s a spirited woman.”

Britt is interested in a spot on the Appropriations Committee — which, if she lands it, would continue Shelby’s legacy of delivering billions of dollars to their state’s defense industrial base, harbors, universities and more. Her ambition sharply contrasts with that of Brooks, “an outsider,” according to Shelby.

“I didn’t think he’d be good for Alabama,” Shelby said. “He’s against everything.”

That candor is a fitting reminder of what Shelby’s trying to pull off this week: a legacy-sealing agreement that could be the Hill’s last big spending deal for years. It’s the type of legislation that contains a lot of provisions Shelby would vote against if they stood alone — but as a whole, sums up his old-school approach.

“You can’t be against everything. I’m pretty conservative in a lot of ways, but I’m not against everything,” Shelby said.

Paul Kane, WaPo (“‘We won that’: How Shelby beat the FBI, an ethics committee and Trump“):

In 1992, running as a conservative Democrat not aligned with his party’s presidential nominee, Richard C. Shelby cruised to victory with 65 percent of Alabama’s vote.

By 2016, running as a Republican not supportive of his party’s presidential nominee, Shelby cruised to victory with 64 percent of the vote.

In all the years, the ups and downs of 36 years in the Senate and eight years in the House — 16 as a Democrat, 28 as a Republican — Shelby cut a path as one of the great political survivors of this era.

[…]

His career is a rebuke to two trends in today’s Senate: those who rush to social media and cable news with outlandish actions seeking attention, and those who sit quietly on the legislative sidelines and do as their party leaders instruct.

“If all you’re interested in is doing everything to please everybody — to say, ‘This is to help me get reelected’ — you’re going to be a House member or a senator of no consequence up here,” Shelby said in a long interview Monday inside his office, where just about everything had been boxed up and sent to storage. “And you’ll be here for the wrong reason.”

Shelby believes his steady popularity back home comes from understanding that voters still value a “senator of consequence,” particularly in the mold of the old-time Southern senator who spent decades acquiring power and using it to help constituents.

[…]

Early on he asked the Senate majority leader, Robert C. Byrd (D-W.Va.), for a seat on the Appropriations Committee. “Definite Republican tendencies,” Byrd told senior Democrats, explaining his rejection.

Shelby quickly discovered that the days of Southern conservatives dominating the Democratic caucus had passed, and after he won a second term in 1992, he openly feuded with President Bill Clinton. White House officials retaliated by offering Shelby just one ticket to the ceremony honoring Alabama’s national football championship. Howell Heflin, the state’s Democratic senator, got 15 tickets.

The day after Republicans swept the 1994 midterm elections, Shelby switched parties. He set out to reshape his state’s economy, beginning with Huntsville.

“A few decades ago, it was a sleepy town by the Tennessee border. Today, it’s a booming technological hub for cutting-edge industries like space exploration and missile defense,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said in a tribute speech to Shelby.

And a trip to Singapore led Shelby to turn Mobile’s port into one of the deepest in the nation.

[…]

Almost nothing changed politically, as his reelection came in like clockwork, always between 63 and 68 percent, but then ahead of the 2016 campaign, Shelby heard footsteps.

Several veteran senators had been caught by hard-charging ideologues in GOP primary campaigns, so Shelby got ready, hiring McConnell’s top political advisers to run a modern campaign. Trump’s ascendancy in Alabama complicated matters, bringing out many first-time voters who weren’t natural Shelby supporters.

“I never ran with Donald Trump. No, I didn’t. I ran ahead of him 20 points,” Shelby said. He won his primary with 65 percent of the vote, well ahead of Trump’s 43 percent plurality.

In his final term, Shelby tried to play the role of institutional caretaker. When The Washington Post broke news that, in his 30s, Republican Senate nominee Roy Moore of Alabama had romantically pursued teenage girls, Shelby broke ranks in that 2017 special election.

“He would’ve been the face of the party for the wrong reasons, and the face of Alabama for the wrong reason,” Shelby said Monday.

He announced he would write in a different candidate, and nearly 23,000 Alabamians followed suit.

A two-year-old AL.com report speculating on his future (“What happens when Richard Shelby leaves office? Alabama Senator’s influence seen in massive spending bill“) contains this:

With Shelby’s political life coming to a possible end within two years, political observers are also harkening on the phrase: You don’t know what you got until its gone.

“Most Alabamians won’t fully appreciate the enormous impact of Alabama’s longest serving U.S. senator until he leaves the Capitol,” said Phillip Rawls, a retired journalism professor at Auburn University and a longtime former political journalist with The Associated Press.

Said Steve Flowers, a former Republican member of the Alabama statehouse and a longtime observer of state government, “Alabama will realize in five years, once he’s gone, that we’ll be behind the eight-ball. When Shelby leaves, it will be all over.”

[…]

“There aren’t many people like Senator Shelby who know how to bring home financial benefits to their state,” said Brent Buchanan, a Republican Party strategist based in Montgomery. “Without someone like Shelby in the U.S. Senate — which takes both tenure and tenacity – Alabama will lose out on billions of dollars of federal largesse.”

Alabama politicians continue to praise on Shelby, whose influence in the Senate is credited with transforming the state’s economic attractiveness. On Tuesday, for example, Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson pushed out a news release thanking the senator for his role in securing funding for the Port of Mobile and for the city’s new commercial aviation terminal at the Brookley Aeroplex.

“It is hard to overstate the role he has played in Mobile’s quest to become a world class city and global competitor in multiple industries,” Stimpson said. “From education to defense to commerce to transportation – there’s virtually no sector of our economy Senator Shelby hasn’t impacted at the federal level. His continued to support benefits not just Mobile but our whole region and the entire state.”

At the Alabama State Docks, where Shelby has led federal efforts to secure billions for a crucial dredging project, the accolades continued.

“I can absolutely affirm that modernizing Alabama’s seaport could not have been achieved without Senator Shelby’s support,” said Judy Adams, spokeswoman with the Alabama State Port Authority.

Shelby rarely grants one-on-one interviews and his public appearances in the state are relatively low-key and limited affairs. In Mobile, for instance, his only public appearance in recent years was during a Chamber of Commerce breakfast sponsored by the Alabama State Port Authority where he further championed the widening and expansion of the ship channel to accommodate bigger vessels and to bolster Alabama’s economic development.

“Shelby keeps his mouth shut and does his work, builds relationships across the aisle and knows how to ‘bring home the bacon’ as they say in the U.S. Senate where that is everyone’s primary goal,” said Wayne Flynt, a historian and professor emeritus at Auburn University. “He is non-ideological, which is another key to success when you are the minority party in the White House.”

Flynt said that Shelby’s tenure in the Senate, which began in January 1987, doesn’t include a record of sponsoring “transformational legislation or key roles in leadership such as Alabama senators of the past: Will and John Bankhead, John Sparkman and Lister Hill.

“But I would rank him as a 10 in terms of helping the state,” said Flynt.

Flowers goes further with his praise. He calls Shelby the greatest senator elected ever in Alabama.

I’ve never been a big Shelby fan—I haven’t forgiven him for the mean-spirited, dishonest campaign he ran against war hero Jeremiah Denton to win the Senate seat—but it’s hard to deny that he’s been incredibly effective. And, by Senatorial standards, he mostly did what he believed was right for his constituents, playing the long game the six-year term is designed to encourage. The irony that a man known for his colleagues for “the taxman cometh” line has brought far more in taxpayer money to Alabama than the state puts into the federal treasury is worth noting but, hey, that’s politics.

While I’ve long railed against octogenarians being so prevalent in our politics, it’s undeniable that the Senate Shelby joined in 1987 was a more collegial, effective governing body than the one he’ll leave in 2023. Back to the NYT piece we started with:

Mr. Shelby honed his tactics at a time when lawmakers across the political spectrum were willing to set aside ideology and unite behind a common zeal for grabbing federal money for their states and districts. That smoothed the path to passing major spending deals and keeping the government running in large part because those lawmakers had a vested interest in securing wins for their constituents.

He unapologetically followed in the footsteps of predecessors known in congressional parlance as “old bull appropriators,” like Republican Ted Stevens of Alaska, Democrats Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii. They saw their primary task in Congress as steering as much money as they could to their states, which they saw as neglected in favor of more populous ones with more influence.

“They trained me,” Mr. Shelby said.

The ascendant right-wing Republicans who wield the greatest influence in Congress these days have received different training altogether.

They are lawmakers who reflexively vote against any federal funding measure and regard big spenders like Mr. Shelby as establishment stooges who have been corrupted by the lure of wasteful government spending. And as the party prepares to assume the House majority next week, they have made it clear that they will demand severe cuts, potentially leading to the kind of spending stalemate that has become commonplace in recent years.

“Other people would say, ‘Oh you shouldn’t do anything for your state, you shouldn’t spend any money on this.’ I differ with that,” Mr. Shelby said last week, sitting in his office in Washington, feet away from his desk that once belonged to another Southern senator who used his perch in Congress to build his state, Lyndon B. Johnson.

Part of the task of a senator, he argued, is to help build the conditions for his state’s prosperity.

“I’m a pretty conservative guy in a lot of ways,” Mr. Shelby said. “But I thought that’s the role Congress has played since the Erie Canal.”

When I was a younger man and Robert Byrd was using his tenure as chair of the Appropriations Committee to become the “King of Pork,” I found the whole notion of earmarks and pork barrel politics outrageous. While there are legitimate reasons to build federally-funded facilities in West Virginia and Alabama, doing so on the basis of who has been in the Senate the longest and wields the most powerful chairmanships is, frankly, corrupt. While I’m happy to see Alabama, a relatively poor state, get federal money, that Shelby brought home twice as much money in this budget as the next Senator is simply not right.

At the same time, the wheeling and dealing in exchange for votes had a tremendous upside. It forced Senators and Representatives to build relationships, even across party lines, and cooperate. While there was doubtless significant fraud, waste, and abuse that came with that, it meant that most were there to govern.

To be sure, the blame for the new attitude mostly goes to my former and Shelby’s current political party. While Ronald Reagan famously quipped, “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help,” he was, in fact, interested in getting laws and budgets passed and, having spent eight years governing California, instinctively understood the need for relationship building and compromise. While Newt Gingrich did quite a bit during his relatively short tenure as Speaker to break down the collegiality of the institution, he was, at the end of the day, a policy wonk interested in getting things done. With the rise of the Tea Party Caucus after the 2010 elections, that all changed: the new breed actually believes the rhetoric and thinks government is inherently a bad thing rather than a tool that can be put to good and bad purposes.

While there is some truth to this, it’s worth considering that these powerful chairmanships go to the Senator’s who have worked the hardest without letup. You can’t jump from four terms on the Senate Flower Committee to the chairmanship of the Appropriations. You have to put in the years on your desired committee ahead of time. In the end, those most adept at working the system, any system, are going to get the most benefit.

And while I wonder if we would be better off limiting the chair to one term, I see that hadn’t done the Republicans much good in the house and, more importantly, has contributed to the weakening of the committees to the advantage of the Presidency.

In a way, Shelby and senators and representatives like him operated as the drafters of the Constitution imagined with each representing their region and state, while developing shifting coalitions to accomplish common goals.

The return of earmarks would benefit the country and make Congress a more effective place. Those Rs who view Shelby and those like him of being “establishment stooges” are projecting, as they are fronting and representing a small cabal of wealthy political donors and not the constituents that elected them.

My personal interest is whether the Senate, sans Shelby, will continue to hamstring project Artemis by continuing to force a horrible technical solution on NASA because it made Sen. Shelby happy. Or if they’ll decide to take the SLS/Orion cash cows away from Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

Expanding on my comment about the weakening of the House committees by term limiting the chairman, it is not unreasonable to say that Gingrinch’s maneuver to make chairs more dependent on the speaker resulted in shifting power to someone who has no actual agenda other than staying in power, and by limiting the term of the chair to six years reduced the incentives of the committees to work across party lines. In the past a chair might come in and out of the seat several times as control of the house shifted, and so there was an incentive to treat the other party’s members with some respect, as the tables could be turned at the next election.

In the end the Committees have become less about accomplishments and more about grandstanding. Since they no longer want to control and guide their charter areas, the President has stepped in to fill the vacuum.

@MarkedMan: While I think Gingrich was malicious in many ways, I believe that move was well-intentioned without thinking through second-order effects. Remember, it wasn’t back and forth in those days. Democrats has enjoyed uninterrupted control of the House since the 1950s.

@MarkedMan:

The real problem isn’t term limiting committee chairs, but shifting power to the speaker. Term limits have resulted in House R churn, few former committee chairs are interested in being back-benchers, so they retire. That should be a good thing, but given that the R party has lost its mind…

@James Joyner: @Sleeping Dog: Good points. In the end it is often hard to predict what the effects of a change are going to be long term.

James, I t’s interesting that you think of Gingrich’s motivations here as well intentioned. I always assumed that his primary motivation was to get rid of the power of the Republican senior members, who would defy him if it meant it would further their agenda. He immediately put the junior members on notice that a) regardless of seniority they could be the next chair, and b) if they wanted to be that chair they needed to suck up to the Speaker, not the Dems.

To suggest a variation on a theme: porkbarrel spending is the worst way to do fiscal policy, except for all the others that have been tried.

In a perfect world, the Senate (alongside the House) would work together to find policies that benefited the entire country. But if the only way to get major infrastructure projects accomplished is to wheel and deal and not have it be utterly fair, so be it. It beats not governing.

@MarkedMan: It’s possible, I suppose. I was way less cynical in January 1995 and was looking through different lenses. But I think he honestly saw the abuses of power under the old Democratic lions and thought we should fix them with term limits. Indeed, part of the Contract With America was a pledge to serve only 12 years, period, in one house.

@Michael Cain:

I wonder whether NASA should get out of the launch system business, and instead request proposals from industry along the lines of payload weight and delta-v.

That way they can focus on spacecraft design, like the Apollo Lunar lander, space probes, rovers, etc.

“Yeah, we wanted to use old Shuttle parts. But the Shotwell Starship+ proposal is far superior. Now, Senator, about the Lunar base and mining station…”