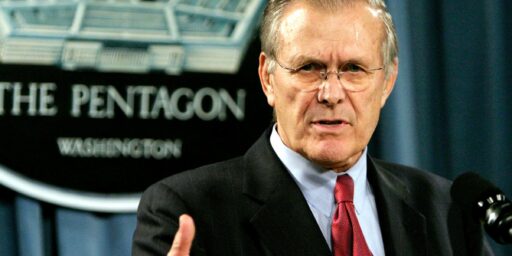

Rolling Back Rumsfeld’s Private Intelligence Service

Defense Secretary Robert Gates is “considering a plan to curtail the Pentagon’s clandestine spying activities, which were expanded by his predecessor, Donald Rumsfeld, after the 9/11 attacks,” reports National Journal‘s Shane Harris.

This could include changing the mission of the Pentagon’s Strategic Support Branch, an intelligence-gathering unit comprising Special Forces, military linguists, and interrogators that Rumsfeld set up to report directly to him. The unit’s teams work in many of the same countries where CIA case officers are trying to recruit spies, and the military and civilian sides have clashed as a result. CIA officers serving abroad have been roiled by what they see as the Pentagon’s encroachment on their dominance in the world of human intelligence-gathering.

This shouldn’t be surprising:

Gates headed the CIA under President George H.W. Bush and was the only director in the agency’s history to rise through the ranks from entry-level employee. He has criticized the Defense Department’s ascendant role in espionage. In a May 2006 op-ed in The Washington Post, he wrote, “More than a few CIA veterans — including me — are unhappy about the dominance of the Defense Department in the intelligence arena and the decline in the CIA’s central role.” In written responses to senators’ questions before his confirmation hearing, Gates said, “Clearly, if confirmed, this will be an area that I would look into.”

The issues that motivated SSB’s creation are still with us:

The precise details of how Gates could move the military out of the CIA’s espionage territory, while satisfying combat commanders’ desire for on-the-ground intelligence, are still being worked out, former officials said. But the contours now taking shape strike the balance that Gates has indicated he wants: giving primary authority for human intelligence-gathering to the CIA, which falls under the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

[…]

The Defense Department has had its own human intelligence service since 1993. But it was never as expansive as the CIA’s operations directorate, which has since been renamed the National Clandestine Service and is legally designated as the lead human intelligence agency.

When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, the CIA had marshaled rebel forces to help overthrow the Taliban. Rumsfeld recognized that the military’s long-standing reliance on the CIA for on-the-ground intelligence could keep his department in a subordinate role in the war on terrorism. It was well known that the CIA’s spying capabilities, particularly in the Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries that were then of top concern, had degraded in the wake of major intelligence cutbacks after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Neither the CIA nor the military had enough spies to wage a new war on terrorism.

Rumsfeld wanted the military to take a leading role in the global hunt for terrorists, so he expanded the Defense Department’s own capabilities to gather intelligence and to recruit spies abroad. This led to creation of the Strategic Support Branch and the clandestine deployment of small Special Forces teams to U.S. embassies. There, in civilian clothes, they worked as intelligence operatives, recruiting sources within governments or Islamic groups.

Bureaucratic infighting, shockingly, ensued:

But those efforts upset CIA officials, particularly station chiefs, who are supposed to run the spy networks in their assigned countries. Many experts criticized the military’s espionage efforts as bungled attempts by ill-trained personnel. In December, the Los Angeles Times reported that members of one Special Forces spying team, known as a military liaison element, or MLE, shot and killed an armed assailant trying to rob them outside a bar in Paraguay. In East Africa, MLE members were arrested by a local official after their spying was exposed. Those incidents reinforced a long-held opinion among civilian intelligence professionals that military personnel aren’t suited for clandestine spying. “Most people regarded Defense human intelligence services as a group of bozos,” said one former CIA official. “They were incompetent. Their training tended to be substandard.”

Military intelligence officials counter that the CIA hasn’t always met their needs for tactical intelligence in war zones. “When I was in the Balkans, I was not confident that the CIA would provide what I needed on the ground,” said retired Maj. Gen. James (Spider) Marks, who ran the Army Intelligence Center at Fort Huachuca, Ariz., the service’s training school, and was the senior intelligence officer for all U.S. ground forces during the Iraq invasion. Marks said that coordination between the CIA and the military improved after the 9/11 attacks. “The agency was bending over backward to be cooperative” and to allow military commanders to “dip into their capabilities,” meaning they could see what intelligence the CIA had collected on certain people and targets.

But the military still needs its own teams, Marks insisted. “The bottom line is, we don’t have enough tactical human intelligence capabilities. We need guys in Humvees.” Marks said he doesn’t know any details about how Gates might change the military’s role, but he was skeptical about any rollbacks. “If Gates wants to transfer those responsibilities back to CIA and say, ‘You own the responsibility of being first in theater and providing the human intelligence backbone, source structuring, and vetting,’ that’s good. But I would never trust that.”

To one who has studied interservice rivalry between the Army and Air Force, this fight is familiar. The bottom line is that the CIA and military have very different priorities, with the former more concerned about the “big picture” and the latter in need of down-and-dirty intel that can help them get the bad guys and stay alive will doing so.

So, how to fix things?

Intelligence experts said they don’t expect Gates to reduce the military’s or the Defense Department’s abilities to collect tactical intelligence in war zones. “There are things that the Defense Department can do with targeting that are tactically going to be needed within DOD,” said Rep. Pete Hoekstra, R-Mich., the ranking member of the House Select Committee on Intelligence. Hoekstra acknowledged that “the military wasn’t satisfied” with the quality of intelligence it received from the CIA before 9/11. “But the answer to that is not going off and creating a parallel universe,” he said. “The answer is working with CIA and telling them what they need and where they’re coming up short…. The problem I have is that every time Rumsfeld didn’t get the support he needed, he said, ‘Screw it. I’ll do it myself.’ “

Hoekstra, like other experts, said that Gates could make intelligence changes under his own authority without approval from Congress. “I don’t think he necessarily has to brief us on it. Not formally.”

Others predicted that if Gates reins in the Pentagon’s spymasters, it will trigger a storm of opposition. “In the six years since 9/11, the military intelligence community has developed a sense of bureaucratic ownership,” said Matthew Aid, an intelligence historian. “They spent a lot of money developing their own sources and capabilities. There will be a great deal of opposition to giving the CIA these resources.”

The bottom line is convincing everybody that they’re on the same team. It took decades to accomplish this within the Defense Department, and they all worked for the same chain of command.

Theoretically, the existence of the National Security Council and the new National Intelligence Director position are supposed to solve this problem, ensuring that everyone has access to the information and gets high-level input into directing the resources. In reality, though, no one is ever satisfied and the bureaucratic incentives of the non-Defense intelligence community are not conducive to getting useful battlefield intelligence, anyway.

Rumsfeld’s reaction, as was his wont, was often excessive. But it was at least understandable. There was a war on, his commanders weren’t getting the intel they needed, and he had the wherewithal to do something about it. Unfortunately, his method created groupthink and the perception (albeit largely unbacked by evidence) that he wanted the intelligence to confirm what he already thought.

On balance, though, I agree with Steve Clemons that this is a good and necessary move on Gates’ part. Rumsfeld swung the pendulum too far in the wrong direction and it’s time to fix that. Hopefully, the end result will be a more responsive intelligence relationship.

I suspect that like most bureaucrats, Gates actions won’t necessarily match prior rhetoric when it comes to toys now in his hands.

My $0.02 here. I have a vested interest in this as i view this from the DoD perspective. CIA has never voluntarily shared its information and was dragged kicking and screaming into supporting the military commander. They always see themselves as supporting the decision makers, i.e, POTUS, NSC, etc. Now with GWOT in full swing, they want a slice of the military pie as that’s where the action is. DoD would never have stood up its own HUMINT effort if the CIA had willingly support DoD requirements. It’s interesting to see how Gates will pacify the DoD intelligence components. We all know he’s ex-CIA, so where does his loyalty lie?

DCL,

Yeah, the CIA’s always had a bad rep, primarily because they don’t work for the military commander, and therefore their marching orders (and maybe personal priorities) don’t always match up with the military’s needs. Certainly not their timeframe.

But frankly, the CIA’s got a point too – the military just isn’t ever going to be able to set up a true HUMIT operation – their field intel is pretty much limited to recon/direct observation of enemy forces, with some occasional interrogation opportunities. And it’s not up to the military to decide if jeopardizing an active in-country network is worth the benefits (even up to saving lives) to the military operation – losing that network may be more dangerous to the US in the long run.

That’s the bottom line. The military wants someone who is accountable to the on the scene commander. CIA could always find an excuse why they can’t support when it’s convenient to say so. But then they also want to do “sexy” ops like taking out terrorists with predators. Is THAT a military mission? I’m currently reading this for a class and it gives a good primer on the current situation in the IC, though Lowenthal shows his CIA bias.

Long URL affixed to word “here” rather than as separate, incredibly long line. – jhj

Legion

Where do you get your information?

The Defense department has had a true HUMIT for a longer time then the CIA. The CIA was actually an offshoot of one. Thinking of Direct Actions recon and Special recon as only intelligence the defense department has ever done is just wrong.

Maybe you are trying to be slick and taking only the generally thought of military unit mission part out of entire defense intelligence. I will remind you that Gates is in charge of entire department of defense and not just military field units.

Looks like a need a drive-in theater screen to read this post and the thread. Thanks, DC.

Fixed. -ed.

Umm, I didn’t say the DoD _never_ did much HUMINT; just that it’s not the main focus of military intel assets. HUMINT involves gathering intel from humans; either our covert/overt spies or from other people directly – that’s something the CIA more than any other US agency, trains specialized people for. They’re the best we’ve got at it. They just have to be made to ‘play nice’ with other agencies…

Legion, you need to differentiate between tactical military intelligence and national military intelligence. I can tell you national level DoD intel components do quite a bit of HUMINT collection. Also, the military attache corp in DIA’s Directorate of Operations has more collectors than the CIA’s DO.

Legion

You said “But frankly, the CIA’s got a point too – the military just isn’t ever going to be able to set up a true HUMIT operation – their field intel is pretty much limited to recon/direct observation of enemy forces, with some occasional interrogation opportunities.â€

Oh I’m sure you meant that they don’t and never will instead of that they never did.

Unless you were trying to be slick like a stated earlier by parsing out the tactical military out of DOD or playing word games, then your statement says “the DoD _never_ did much HUMINTâ€. As DC Loser said DOD has and does do HUMINT.

Isn’t there the Intelligense Support Activity?

The DoD group that includes HUMINT gatherers, SIGINT gathers, as well as analysists and shooters?

Its incorrect to state the military is wrong to have its own HUMINT service. The military human intelligence need grew out of the failure to rescue the American hostages in Iran, as well as legitimate experience in Vietnam. The military has a need for operational, actionable intelligence the CIA cannot or will not provide. The CIA has traditionally been piss-poor at either sharing intel (see the Iran Hostage crisis/rescue fiasco), or at recruiting people who can do things other than the cocktail party circuit or wait for walk-ins. The CIA has done a poor job at developing indigenous in-the-market sources, or non-diplomatic cover, or working with the military to give information military missions need, such as tactical intel and intel that benefits military missions.

so it is incorrect to state the military does not have a need for HUMINT. as someone outlined before.

Good coverage of this development.

As a former “tactical human intelligence” guy, I can say that the CIA could never possibly hire enough agents to do this job for the military, even if it wanted to do so.

I’ve quoted you and linked to you here.

“the CIA’s got a point too – the military just isn’t ever going to be able to set up a true HUMIT operation – their field intel is pretty much limited to recon/direct observation of enemy forces, with some occasional interrogation opportunities.”

Legion, that’s somewhat correct. Reconnaissance and direct observation (a.k.a. “scouting” and “spotting”) are basic military functions which are indeed intelligence-gathering functions. As are interrogations.

The tactical human intelligence (“tactical humint”) also includes combines force protection source operations, sort of a fusion between what used to be called “low level source operations” and another acronym which escapes me at the time of this writing. The idea is that the commander has THTs (tactical humint teams) deployed in his area of operations which are going outside the wire, making friends and influencing people. When you do that, people talk to you and you can get a handle on what’s going on within your AO.