Scalia Invokes Foreign Law

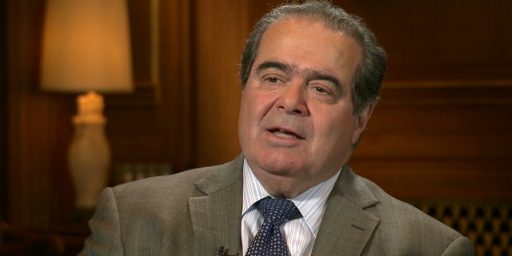

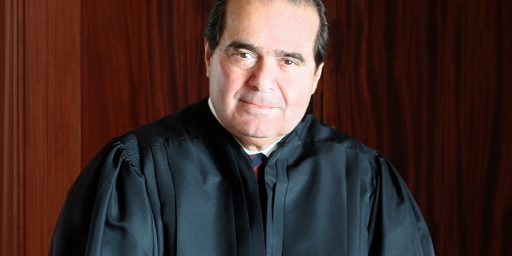

In what some are viewing with irony, Antonin Scalia yesterday referenced decisions of courts in other nations in discussing how the Supreme Court should interpret an international treaty.

In what some are viewing with irony, Antonin Scalia yesterday referenced decisions of courts in other nations in discussing how the Supreme Court should interpret an international treaty.

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia practically hisses when his colleagues consult foreign law to help interpret the U.S. Constitution. But on Tuesday, Scalia found himself looking approvingly to other countries in a case over an international custody dispute.

The court is taking its first look at how American authorities handle the Hague Convention on child abduction, aimed at preventing one parent from taking a child to another country without the other parent’s permission.

“The purpose of a treaty is to have everybody doing the same thing,” Scalia said, “and I think, if it’s a case of some ambiguity, we should try to go along with what seems to be the consensus in other countries that are signatories to the treaty.” That view seemed to put Scalia, who has said the same thing before, on the side of a British father who accused his estranged American wife of violating Chilean law and a court order in Chile by taking their son to Texas without his consent. The child, born in Hawaii and now 14, is a U.S. citizen.

Timothy Abbott asked an American court to order the child returned to Chile, based on the treaty. The mother argued that she has exclusive custody of the boy and that U.S. courts are powerless under the treaty to order his return. The New Orleans-based 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the mother, Jacquelyn Abbott.

The high court appeared inclined to side with Timothy Abbott, although some justices raised concerns that a decision in his favor in this case could lead to undesirable results in others. Chief Justice John Roberts wondered who would decide whether a child should be returned “if you have the mother taking her daughter from, say, a country where she would be forced to be raised under Sharia (strict Islamic) law.” Justice Stephen Breyer said he worries about the case of a father who shouldn’t have access to his child, but who lives in a country that forbids one parent from taking a child to another country without the other parent’s consent. “Even Frankenstein’s monster is considered to have custody for the purposes of this,” Breyer said, despite a family law judge ruling, “‘Don’t let him near that child.'”

Breyer and Scalia, who often square off about the value of foreign law in the Supreme Court, joined Tuesday to help count up countries that have ruled on the child abduction treaty.

While Scalia’s position looks inconsistent, it actually makes perfect sense.

The fact that there is a growing international consensus against the death penalty, for example, has no bearing whatsoever on how American courts should interpret American law. It’s a purely domestic issue, so only the American Constitution, American statutes, and American judicial opinions are relevant. By contrast, the whole point of an international treaty is to standardize conduct among signatory countries. Naturally, then, the way courts in those countries have decided similar cases is valuable in setting precedent.

As to the specifics of the case, I’m insufficiently informed or interested to have an opinion. My general predisposition, however, is that courts ought to judge these cases based on the law — which decidedly includes the relevant international treaties — rather than on the basis of what a majority of the Supreme Court thinks the best outcome in a particular case. This isn’t family court, where “the best interests of the child” is the governing factor. The paramount consideration has to be the uniform enforcement of the law, so that it’s reciprocated when other countries are holding American citizens. The result of that, alas, may well be unfortunate outcomes in specific cases.

Agreed. In this case.

This is incorrect in the context of Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. Since the 1700s, Federal courts have interpreted “cruel and unusual punishment” to be an evolving standard based on consensus, and this idea was confirmed by the Supreme Court in Trop v. Dulles. Under that standard, its perfectly appropriate to look to the practices of other countries in determining whether a particular punishment falls under this rubric.

I’ve never understood how execution, per se, could be an 8th Amendment issue since it’s specifically enshrined in the contemporaneous 6th and subsequent 14th Amendment.

Beyond that, even if something is an evolving standard, the relevant factor is how it’s evolving domestically. Sharia law is becoming more prevalent in much of the world. It doesn’t follow that we can be more cruel in the American criminal justice system, since it’s now less unusual.

Or worse, we would all have to become soccer fans if Americans were subject to evolving global standards. And even worse still, we would have to call it football!

As a general rule I believe Scalia is contemptible. (This has nothing to do with my observation as follows, but I like saying it.) James Joyner is dead right on this one. Scalia is not being inconsistent, merely sensible.

“The fact that there is a growing international consensus against the death penalty, for example, has no bearing whatsoever on how American courts should interpret American law.”

Actually, the guiding principle is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (of which the US is a signatory).

Article 5

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Almost all of the signatory nations have banned the death penalty because their courts, or legislatures, find it is cruel or inhuman punishment. Thus, as a signatory, the court has a duty to look to the other signatories and how they define “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” If those signatories say the death penalty violates these principles then the court has a responsibility to weigh whether we are misinterpreting the relevant treaty.

The U.S. Constitution trumps international treaties.

Mr. Joyner,

You state:

“By contrast, the whole point of an international treaty is to standardize conduct among signatory countries. Naturally, then, the way courts in those countries have decided similar cases is valuable in setting precedent.”

I’m only applying the standard you gave to the issue of the death penalty. If we are to standardize our conduct among the other signatory nations re: Universal Declaration of Human Rights then it is only prudent that we must look to other nations to see how they have “decided similar cases.”

There’s a hierarchy to our law:

– The U.S. Constitution

– International Treaties ratified by the Senate

– Federal statutes

– State Constitutions

– State laws

– Local laws

When dealing with international matters, there’s seldom a constitutional conflict, so treaties will likely be the deciding factor.