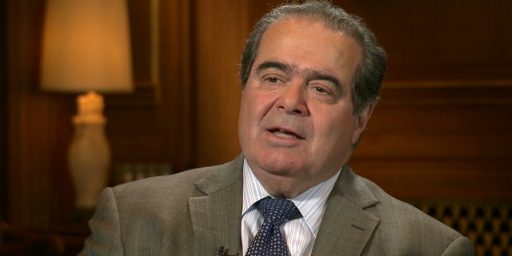

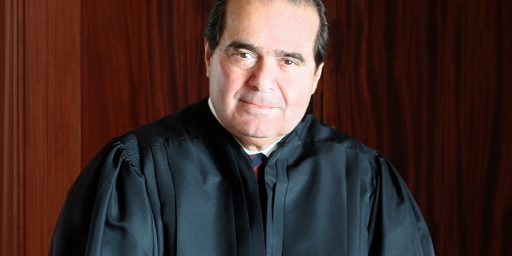

Scalia on Stare Decisis

Vivek Krishnamurthy live blogged Justice Antonin Scalia’s visit to Yale Law, including the Q&A.

I found this especially interesting:

Criterion for following stare decisis should not be whether you think the decision is mistaken or not. The criteria should be how wrong it was.

Scalia uses three criteria in determining whether to overturn precedents:

1) Was the decision wilfully wrong?

2) Has the wrong ruling been generally accepted? (For example, Scalia thinks the incorporation doctrine, which uses the 14th Amendment to apply the Bill of Rights against state governments, is mistaken. That said, it is now so widely accepted that Scalia wouldn’t think about reversing it).

3) Does the existing precedent put me in the role of a legislator rather than a judge? On the abortion question, for example, Roe v. Wade establishes that laws placing “undue burdens” on women’s reproductive choices are unconstitutional. Scalia has no idea on how a judge can figure out whether something is an “undue burden” or not. Such questions should be left to legislative determination.

This quip is even more direct:

Life is too short: you can’t question everything in every case! “Do you want us to review Marbury every time? Go on to the next mistake.”

That strikes me as exactly right. Marbury was indeed incorrectly decided. It is now so ingrained in the system, though, as to be universally accepted as the way it is.

Marbury was indeed incorrectly decided

Whoa. That, like the iniquity of the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a bit much to toss off.

Congress *did* have the power to enlarge the Court’s original jurisdiction beyond what the Constitution permitted?

I think he’s referring to the Marbury decision’s assumption that SCOTUS had the power to nullify laws it considered unconstitutional. A strict textual reading of the constitution simply places the federal government on the honor system to not pass unconstitutional laws.

Anderson:

Fundamentally, yes, Maniakes’ point is my main one.

I would argue, too, that Congress certainly had the power to make cases involving the appointment of justices of the peace part of SCOTUS’ original jurisdiction.

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

First, it’s reasonable enough to say that the case involved a public minister or consul. Second, one could read the second sentence as giving Congress the power to make any exceptions it so desires so long as it does not take away SCOTUS’ original jurisdiction in cases specified in the Constitution.

The case was an amazingly thin reed onto which to hang the seizure of such awesome power, which they did not exercise again in the case of a federal statute until Dred Scot, decades later.

I think both Scalia, and James are being overly pompous here, with their reference to decisions being “wrong” or “incorrect”. There is no objective standard for stating whether decisions are correct or not – they are either decisions that you agree with or not. James may not like Marbury, but that doesnt make it “incorrect” in any sense larger than the meaning “James disagrees”.

So Scalia’s standards for overturning a decision really reduce to:

1) Do I disagree with the decision? (duh…)

2) Is my position so extreme such that it would create chaos were it adopted? (often the case, I’m suspect)

And thats about it. Even shorter version: I will vote to overturn if I can get away with it.

As to criterion 3 – that strikes me as just a bit of deceptive spin – trying to justify ones position by reference to current ideological memes and nothing more.

Determining whether a ruling or a law creates an “undue burden” on anyone is precisely the thing that judges do all the time. Comparing how a law affects an individual’s constitutional rights is what courts have done for over 200 years. It is precisely the type of thing that legislatures DO NOT do very well. Legislatures are political bodies where compromises are made between those with sufficient representation to get a seat at the table. Such a process can often lead to laws that create undue burdens on those who did not have sufficient political power at the moment that the law was crafted. It is inarguably the role of the judiciary to protect the rights of political minorities from the potential tyranny of the majority.

I think that the corollary to Scalia’s arguments is what do you do with stare decisis that is “wrong” and ingrained. And it would seem to me the right procedure there is a constitutional amendment.

Kelo is a modern example, though it would hardly fit Scalia’s rule of being “deeply ingrained”. But if we wanted to reverse the supreme court on this or any other issue such as Marbury, it would seem that a constitutional amendment would be the best way.

Tano,

Another way of reading Scalia here is not “reverse what I can get away with”, but rather reverse what is wrong and where the law of unintended consequences is not likely to make things worse. The more deeply ingrained something is, the more likely that trying to extract it will have unintended consequences.

You also left out the third part which asks the (to the conservative mind at least) rational question of would the ruling put the judge in the role of the legislature. While this question should be asked in the original ruling, the fact that it wasn’t considered shouldn’t grant carte blanc in reversing the original ruling.

The same effect as having killed (God) Jesus, I suppose. It was a mistake, but society has sort of gotten used to it, so we ought to leave it be-no reparations or funny stuff like that.

burdens he would have not overturned Brown V Board of Ed because it had been the law of the land for three generations. Determining whether a ruling or a law creates an “undue burden” is exactly like determining whether a law has a “vested state interest”, and judges have to do it all the time, judges are constantly asked to sort out competing rights. This is simply Scalia rationalizing the inconsistencies in his personal judicial philosophy, nothing more.

That first sentence should have read:

Under his criteria it seems like he would have not overturned Brown V Board of Ed because it had been the law of the land for three generations.

The Idea that a ruling is wrong though is completely arbitrary, based on assumptions, I happen to think the 9th amendment is a good idea and not an “ink blot”. I start out with the assumption that the 9th offers any personal right asserted constitutional protection until the state can demonstrate why it should not be considered a right. Until Scalia can tell me exactly how an unenumerated right is recognized without some conservative calling it legislating form the bench I submit that his judicial philosophy is seriously lacking.

Oh, now I get it. Marbury is wrong for acknowledging the common-law right of the courts to strike down unconstitutional laws, and for failing to allow the other two branches of the gov’t to ignore the Constitution whenever they like.

Cf. John Yoo (of all people):

To say nothing of Federalist # 78.

So … yeah. Marbury‘s wrongness was so obvious that the people, the Congress, and the President immediately reined in the out-of-control Court and impeached Marshall.

Actually, Federalist #78 skirted the issue very nicely. The counter-argument is quite simple: If the Framers had intended the courts to have judicial review, they might have mentioned it in the Constitution. They were, after all, rather explicit about much less fundamental matters.

Judge Gibson’s dissent in Eakin v Raub is considered a classic exposition of the argument.

If this is actually the sense of what Scalia argued, it’s remarkably silly, conflating the leglislative role with so-called “hard cases” (R. Dworkin is all over this stuff like white on rice). That’s why I’ve never cared for Scalia: people think he’s smart when he’s just bombastic. His jurisprudence falls to pieces like a cheap shirt when looked at closely.

Yeah, I misspelled legislative. And I didn’t mean to say I don’t care for Scalia, because I enjoy his opinions quite a bit. He’s just not as bright as people desperately want him to be.

Federalist 78 “skirted the issue”?

The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited Constitution. By a limited Constitution, I understand one which contains certain specified exceptions to the legislative authority; such, for instance, as that it shall pass no bills of attainder, no ex-post-facto laws, and the like. Limitations of this kind can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing. * * *

A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Exactly how could Hamilton have been any clearer? And did Gibson not read Hamilton? The appeal to “public opinion” to rein in the Congress, which was likely as not expressing public opinion when it enacted the unconstitutional law in the first place, is just silly. (No wonder Prof. Scheb’s at the same school as Glenn Reynolds.)

If Judge Gibson didn’t care for the Constitution or the intent of the Framers, that’s fine, but it’s pretty evident that his preferences were not to be confused with theirs.

Tano; in defense of both men, [joyner& scalia]I don’t see even the ability to be pompous in either. i think scalia is very unassuming, considering the fact that he is, by some measure, the smartest justice on the court, and would certainly be on the list of the all time top nine.

*rolls eyes*