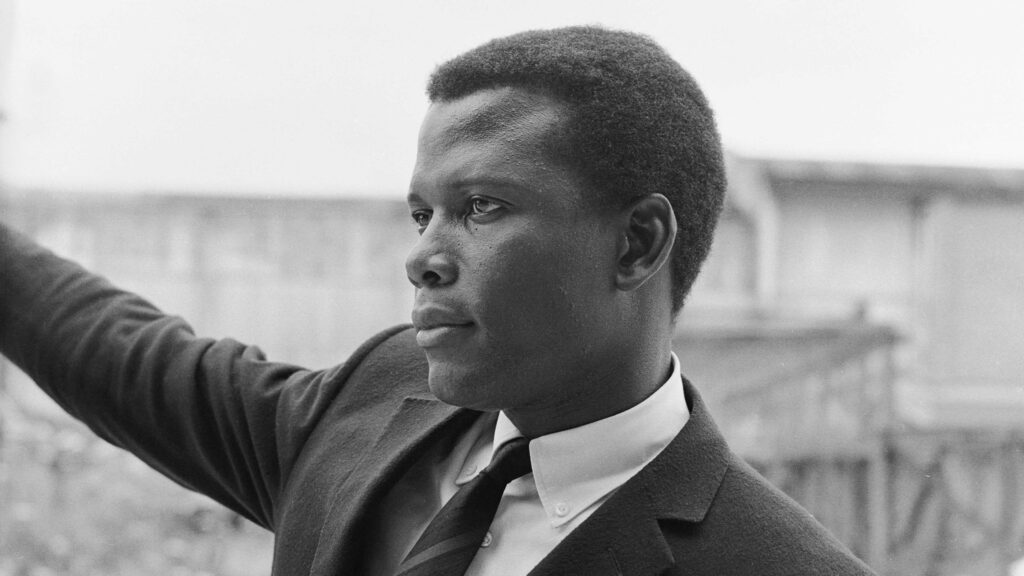

Sidney Poitier, 1927-2022

A pioneering Black actor is gone at 94.

Washington Post (“Sidney Poitier, first Black man to win Oscar for best actor, dies at 94“):

Sidney Poitier, who was the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor and who forever changed the perception of African Americans in movies with his powerful and charismatic screen presence, died Jan. 6 at 94.

The personal assistant to Frederick A. Mitchell, the minister of foreign affairs in the Bahamas, where Mr. Poitier was raised, confirmed the death. Pamela Poitier said her father died at his home in California but did not provide further details.

As a suave and dignified star, Mr. Poitier challenged audiences to accept Black performers in leading roles in movies and on television. He upended a demeaning Hollywood tradition of casting Black performers in vulgar caricature or limiting them to singing and dancing roles that could be segregated from the rest of the film and cut out when the movies ran in the South.

Cornel West, an author, social critic and civil rights activist, called Mr. Poitier “the towering American artist of African descent in the history of film” and likened him to the first Black major league baseball player, Jackie Robinson.

Mr. Poitier’s Oscar was for “Lilies of the Field,” a film released in 1963 — the same year as the civil rights March on Washington. By contrast, the film, about a drifter handyman who helps nuns from Central Europe build a chapel in Arizona, made almost no mention of race, which Mr. Poitier, who championed colorblind casting, deemed as much a triumph as his Oscar.

At a time when much of the country remained segregated, he struggled to find roles as professional and authority figures, saying that his primary intent was to portray Black men of “refinement, education and accomplishment.”

Perhaps his most enduring and defining part was Virgil Tibbs, an experienced Philadelphia homicide detective who helps a bigoted White Mississippi police chief in a murder investigation in “In the Heat of the Night” (1967). The film marked the first appearance of a Black law enforcement hero in a mainstream Hollywood movie.

The chief, played by Rod Steiger, makes fun of the name Virgil and asks Tibbs what he is called in Philadelphia. Mr. Poitier shoots back with a mixture of pride and barely contained rage, “They call me Mister Tibbs.”

In the movie’s most startling sequence, the prominent owner of a cotton plantation slaps Tibbs for not knowing his place, and Tibbs slaps him back reflexively. Mr. Poitier wrote in his memoir “The Measure of a Man” (2000) that it was his idea for Tibbs to return the slap.

“In the original script, I looked at him with great disdain and, wrapped in my strong ideals, walked out,” he wrote. “That could have happened with another actor playing the part, but it couldn’t happen with me.”

He insisted on a change to the script because of a searing experience as a teenager in Florida, when police stopped him for walking in a White neighborhood.

“They really had their fun with me,” he recalled in the book. “They put a pistol right to my forehead. … And for 10 minutes, they just joked about whether to shoot me in the right eye or left eye.”

As much as “In the Heat of the Night” secured his star luster, it was only one in a line of cinematic breakthroughs.

In some of Mr. Poitier’s finest film performances, he was a medical resident harassed by a racist patient (Richard Widmark) in “No Way Out” (1950); an escaped prisoner chained to a bigoted convict (Tony Curtis) in “The Defiant Ones” (1958); and an ambitious chauffeur in “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), a part he also played in the 1959 Broadway play and for which he received a Tony Award nomination.

Mr. Poitier’s place in the 1960s Hollywood hierarchy — a major star with critical and popular appeal — was exceptional in the ranks of Black actors. Harry Belafonte, a popular singer of calypso and other folk songs, exuded more sexual charisma than Mr. Poitier but lacked his range. Belafonte tried to make it as a leading man in the 1950s before returning to a career in music and civil rights.

After his Academy Award win, Mr. Poitier said he doubted that the honor would be a “magic wand that will wipe away the restrictions on job opportunities for Negro actors.” Even at his career’s peak, in the 1960s, he said his creative control was often limited to rejecting roles that he felt were unworthy.

He sought parts in which his skin color was incidental, including the Cold War thriller “The Bedford Incident” and the suicide-helpline drama “The Slender Thread” (both 1965), explaining that he hoped a race-neutral approach to casting would change perceptions in the film industry.

But the thoughtful, unthreatening image he projected — playing a doctor engaged to a White woman in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and a London teacher who tames rowdy students in “To Sir, With Love” (both 1967) — was out of step with increasingly assertive Black activism. In some quarters, Mr. Poitier came under withering attack.

Writer Larry Neal was among the Black activists and artists to scold Mr. Poitier, calling him in 1971 “a million-dollar shoeshine boy.” Melvin Van Peebles, who made the politically radical film “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971), wrote decades later in Ebony magazine, “Sidney was a wonderful actor, and we were proud, but nobody could really relate because the characters he was given to play were surreal, more from heaven than the ‘hood.”

Mr. Poitier was hurt by such criticism, but he understood it. He wrote in his first memoir, “This Life” (1980), that few starring roles presented “positive images” of Blacks and that “however inadequate my step appeared, it was important that we make it.”

Film critic and scholar Richard Schickel said many in the Black community, as well as some White movie critics, wanted Mr. Poitier “to lead the revolution in the movies. But in truth, the movies were somewhat behind the ‘revolutionary curve.’ So what was on offer for Mr. Poitier was being a middle-class guy who, to a degree, challenged White smugness.”

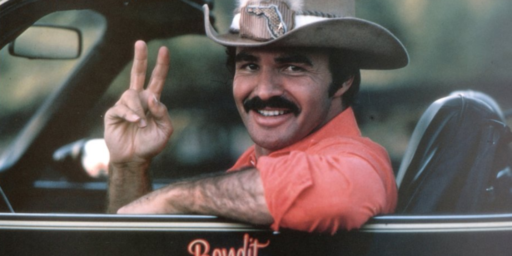

Directing became a way for Mr. Poitier to assert control over his image and, starting in the 1970s, he made comedies starring Bill Cosby (“Uptown Saturday Night,” “Ghost Dad”), Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder (“Stir Crazy”) and Wilder and Gilda Radner (“Hanky Panky”).

After being off the movie big screen for 10 years, Mr. Poitier returned in a pair of action thrillers in 1988, playing FBI agents in “Shoot to Kill” and “Little Nikita.” Four years later, Mr. Poitier was lured back to portray a cashiered CIA agent in “Sneakers” (1992), with Robert Redford and Dan Aykroyd, because “it was a wonderful, breezy opportunity to play nothing heavy. It was simple, and I didn’t have to carry the weight. I haven’t done that in a while, and it was refreshing.”

New York TImes (“Sidney Poitier, Who Paved the Way for Black Actors in Film, Dies at 94“):

Sidney Poitier, whose portrayal of resolute heroes in films like “To Sir With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” established him as Hollywood’s first Black matinee idol and helped open the door for Black actors in the film industry, has died at 94.

[…]

Mr. Poitier, whose Academy Award for the 1963 film “Lilies of the Field” made him the first Black performer to win in the best-actor category, rose to prominence when the civil rights movement was beginning to make headway in the United States. His roles tended to reflect the peaceful integrationist goals of the struggle.

Although often simmering with repressed anger, his characters responded to injustice with quiet determination. They met hatred with reason and forgiveness, sending a reassuring message to white audiences and exposing Mr. Poitier to attack as an Uncle Tom when the civil rights movement took a more militant turn in the late 1960s.

“It’s a choice, a clear choice,” Mr. Poitier said of his film parts in a 1967 interview. “If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains and to deal with different images of Negro life that would be more dimensional. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game.”

At the time, Mr. Poitier was one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood and a top box-office draw, ranked fifth among male actors in Box Office magazine’s poll of theater owners and critics; he was behind only Richard Burton, Paul Newman, Lee Marvin and John Wayne. Yet racial squeamishness would not allow Hollywood to cast him as a romantic lead, despite his good looks.

“To think of the American Negro male in romantic social-sexual circumstances is difficult, you know,” he told an interviewer. “And the reasons why are legion and too many to go into.”

Mr. Poitier often found himself in limiting, saintly roles that nevertheless represented an important advance on the demeaning parts offered by Hollywood in the past. In “No Way Out” (1950), his first substantial film role, he played a doctor persecuted by a racist patient, and in “Cry, the Beloved Country” (1952), based on the Alan Paton novel about racism in South Africa, he appeared as a young priest. His character in “Blackboard Jungle” (1955), a troubled student at a tough New York City public school, sees the light and eventually sides with Glenn Ford, the teacher who tries to reach him.

In “The Defiant Ones” (1958), a racial fable that established him as a star and earned him an Academy Award nomination for best actor, he was a prisoner on the run, handcuffed to a fellow convict (and virulent racist) played by Tony Curtis. The best-actor award came in 1964 for his performance in the low-budget “Lilies of the Field,” as an itinerant handyman helping a group of German nuns build a church in the Southwestern desert.

NBC (“Sidney Poitier, trailblazing Hollywood icon who broke barriers for Black actors, dies at 94“):

Sidney Poitier, the renowned Hollywood actor, director and activist who commanded the screen, reshaped the culture and paved the way for countless other Black actors with stirring performances in classics such as “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” has died, a source close to the family told NBC News on Friday.

[…]

“I felt very much as if I were representing 15, 18 million people with every move I made,” Poitier once wrote about the experience of being the only Black person on a movie set.

He won the best actor Oscar in 1964 for his depiction of an ex-serviceman who helps East German nuns build a chapel in “Lilies of the Field.” The first Black man to win that honor, he remained the only one until Denzel Washington in 2002 — the same year Poitier received an honorary Oscar “in recognition of his remarkable accomplishments as an artist and as a human.”

In the course of his public life, Poitier was the recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1995, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, two Golden Globe awards (including a lifetime achievement honor in 1982), and a Grammy for narrating his autobiography, “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography,” published in 2000.

It’s worth noting that Poitier’s groundbreaking Oscar was awarded just two years before I was born. When I was certainly aware of, indeed surrounded by, racial prejudice of many stripes growing up, there was never a time in my life where it seemed weird that a Black man might star in movies and television shows.

I’m not sure I ever saw “Lilies of the Field,” but probably did at some point. “To Sir With Love” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” are what I primarily remember him for.

As with so many celebrities who have died in their 90s of late, it’s hard to call it a tragedy. He lived a very long and accomplished life.

I adore Sneakers. Sidney Poitier was great in it, and I’m glad to see he enjoyed it. It sure seems like it watching it. In fact, he lets slip a choice bit a swearing at one point, which I’m sure he especially enjoyed since its so against type for him. Mostly in Sneakers he plays off against Dan Ackroyd’s conspiracy-theory mongering, and it’s great. A very different look at a great, great star.

@Jay L Gischer:

While I respect his more powerful roles, it was really fun to see him in Sneakers. That was an amazing cast all around, and it looked like every one of the enjoyed their roles.

During the period of Poitier’s accent I was a schoolboy. Viewing him as an actor through his characters, it struck me that he was a man apart. Not because he was black, but due to the quiet dignity that he projected. For a white kid, growing up in a lily white suburb, whose only contact with blacks and black culture was through actors, musicians and athletes, Poitier’s public persona (and that of other’s such as Bill Russell and Arthur Ashe) planted the seed, questioning the dominant white narrative of blacks was indeed a lie.

Goodspeed

I saw “Lilies of the Field” on television in approximately 1968. I really enjoyed it. Poitier played a more working-class person, and used a bit of black patois for the role. Though no, there was no discussion of race in it, just the knowledge that this was unusual.

And for me, while it wasn’t “weird” for a black man to star in a film, it was unusual, and we knew it was unusual.

Probably the same year I saw LotF on TV, I also watched Lawrence Welk with my dad (he loved music shows of all kinds) and he observed (or was it me?) that the only black guy on LW was the tapdancer named Arthur Duncan. Now, he was a really good tapdancer…no shade there. But different media made different choices.

Now, it turns out this is the same Arthur Duncan who was on the Betty White Show, and whom she refused to fire despite objections from Southern viewers.

They call me Mister Tibbs

Sparta, Illinois and Chester, Illinois are two towns that I covered for the General Telephone Company about 10 years after this film was made. I’ve been over the Chester Bridge many times. Earlier when the toll was 50¢ and later after the toll booth was removed.

The magic of movies!

Looking at the map Sparta, Mississippi is about 150 miles east of the Mississippi River.

If you look closely at about 3:56 in the scene where Chief Gillespie (Rod Steiger) chases Harvey Oberst (Scott Wilson) on the bridge in the background you can see Menard Correctional Center that opened in 1878. Second in age in the Illinois system to Pontiac Prison that opened in 1871.

It is one of the finest slaps in the history of movies. There is a story that it was improvised on the spot that appears to be apocryphal. But the acting is so good (both men definitely slapped each other) and for the time the action was so unexpected that you could believe it was, in fact, improvised:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UrB8TI5El4

And Sneakers is an absolute delight. It’s a film that even at the time felt like it was already from a bygone era (in the best possible way).

A link to Sidney Poitier’s Oscar speeches.

The man was amazing. Bless him and may he be always remembered for his contributions.

Dawg, I’m feeling old these days. So many dying these past few weeks. Just to call out my favorite performances of his in the wikipedia order:

The Defiant Ones

A Raisin in the Sun

Lilies of the Field

To Sir, with Love

In the Heat of the Night

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

They Call Me Mister Tibbs!

Uptown Saturday Night

A Piece of the Action

and of course,

Sneakers

(bolded, my favorite favorites. That slap…)

I was very fortunate to meet Mr. Poitier when he was directing “Fast Forward”. Gretchen Palmer, a friend of mine and one of the cast of that film, invited me to visit set one day while I was visiting NYC. Needless to say, I was nervous and in awe. He was one of my idols growing up. His quiet resolve and dignity were so impressive to me that I wanted to emulate him.

He was so kind and generous with his time. I only spoke with him for about 15 minutes, but it’s something I’ve always treasured.

He was the voice for a whole lot of people for a long time. He handled that weight very, very well.

@EddieInCA:

Small anecdote…. That same Gretchen Palmer ended up being a co-star in an episode of “Tales from the Crypt” that I wrote in 1995 while living and working in England. I had nothing to do with her being cast but it was a hoot when she got to London to do the episode and saw me when she arrived at Ealing Studios. If anyone wants to have a laugh, you can see it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mLNcq6rgKa8

My ending was re-written by our producers, so don’t blame me for it. 🙂

@EddieInCA:..ending was re-written…

Gretchen Palmer Very Nice!!!!!!!

(What about the ending???)

Class act, from start to finish. The world is slightly darker with his passing. RIP sir