Simple Code Breaking?

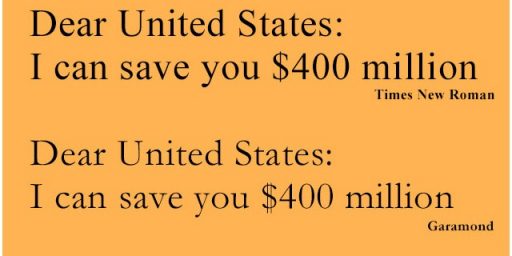

An Irish graduate student came up with one of those “obvious†solutions to a long time intelligence challenge. The United States, and other governments, sometimes release documents that have “sensitive†information blacked out. The solution to revealing what the blacked out material is turned out to be simple. First, you determine the font used in the document, and the font size. This gives you the number of letters in deleted words. Create a program to search an electronic dictionary for words that contain that many letters, then select the words that make sense. While the actually blocked out words are not discovered a hundred percent of the time, they are revealed over half the time. Some intelligence agencies may have already figured this out, but kept quiet lest they lose a good source of secret information.

Now, isn’t the “sensitive” information left out almost always a word that’s not in the dictionary–someone’s name? a location? Otherwise, one wouldn’t need anything even this “sophisticated” to figure out what had been redacted.

Having prepared a couple of documents for public release, the most common item are numbers, either quantities or social security numbers. Guessing the deleted items has kept many pundits busy; this isn’t something new.

Also, sometimes the items deleted are in alphabetical order, which can make things easier. About 5 years ago a list of nuclear weapons storage sites ~1960 was released, and one of the locations had to begin with H or I, so the pundits (Bill Arkin) jumped on it being Iceland, creating a minor diplomatic furor. Turned out the deleted entry was Iwo Jima, which was under American rule at the time.

Here is a related article, where the author chortles over guessing 25 of 27 deleted items.

http://www.thebulletin.org/issues/2000/jf00/jf00norrisarkin.html

The common approach suffers from pure laziness. Rather than provide what is essentially a photocopy of a document, it should be turned into electronic text, and all elided items supplanted with a standard, predetermined text.

Lists, of course, should be either eliminated in their entirety, or deleted items should be left out entirely, so that there’s no indication of what’s missing.

Declassification is a lot harder than most people think, including those who are responsible for ensuring classified information isn’t released inadvertently. An obvious tack would be to have folks who try to crack “the enemy’s” secrets try to crack our own. We do this routinely in the arena called “Signals Security.” It’s hard to believe we don’t employ the same tactics when it comes to declassification.

—