Stanislav Petrov, Soviet Officer Who Helped Avert Nuclear War, Dies At 77

Early on the morning of Sept. 26, 1983, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov helped to prevent the outbreak of nuclear war.

Stanislav Petrov, a former Soviet military officer who was largely personally responsible for what could have been all-out nuclear war, has died at the age of 77:

Early on the morning of Sept. 26, 1983, Stanislav Petrov helped to prevent the outbreak of nuclear war.

A 44-year-old lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Defense Forces, he had begun his shift as the duty officer at Serpukhov-15, the secret command center outside Moscow where the Soviet military monitored its early-warning satellites over the United States, when alarms went off.

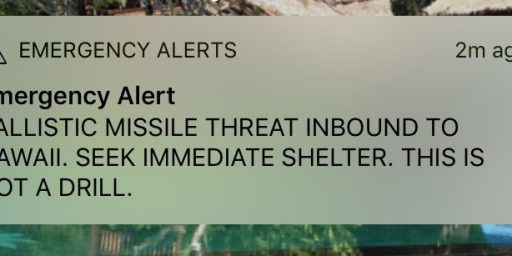

The computers warned that five Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles had been launched from an American base.

“For 15 seconds, we were in a state of shock,” he later recalled. “We needed to understand, ‘What’s next?'”

The close call occurred during one of the tensest periods in the Cold War. Three weeks earlier, the Soviets had shot down a Korean Air Lines commercial flight after it crossed into Soviet airspace, killing all 269 people on board, including a congressman from Georgia. President Ronald Reagan had rejected calls for freezing the arms race, calling the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” The Soviet leader, Yuri V. Andropov, was obsessed by fears of an American attack.

Colonel Petrov was at a pivotal point in the decision-making chain. His superiors at the warning-system headquarters reported to the general staff of the Soviet military, which would consult with Mr. Andropov on launching a retaliatory attack.

After five nerve-racking minutes — electronic maps and screens were flashing as he held a phone in one hand and an intercom in the other, trying to absorb streams of incoming information — Colonel Petrov decided that the launch reports were probably a false alarm.

As he later explained, it was a gut decision, at best a “50-50” guess, based on his distrust of the early-warning system and the relative paucity of missiles that were launched.

Colonel Petrov died on May 19 in Fryazino, a Moscow suburb where he lived alone on a pension, but was not widely reported until now. He was 77.

(…)

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov was born on Sept. 9, 1939, in Vladivostok, Russia. His father had been a fighter pilot during World War II. He studied at the Kiev Higher Engineering Radio-Technical College of the Soviet Air Force.

After joining the Air Defense Forces, he rose quickly through the ranks; he was assigned to the early-warning system at its inception in the early 1970s.

Historians who have analyzed the episode say that Colonel Petrov’s calm analysis helped to avert catastrophe.

As the computer systems in front of him changed their alert from “launch” to “missile strike,” and insisted that the reliability of the information was at the “highest” level, Colonel Petrov had to figure out what to do.

The estimate was that only 25 minutes would elapse between launch and detonation.

“There was no rule about how long we were allowed to think before we reported a strike,” he later told the BBC. “But we knew that every second of procrastination took away valuable time, that the Soviet Union’s military and political leadership needed to be informed without delay. All I had to do was to reach for the phone; to raise the direct line to our top commanders — but I couldn’t move. I felt like I was sitting on a hot frying pan.”

As the tension in the command center rose — as many as 200 pairs of eyes were trained on Colonel Petrov — he made the decision to report the alert as a system malfunction.

“I had a funny feeling in my gut,” he later told The Washington Post. “I didn’t want to make a mistake. I made a decision, and that was it.”

Colonel Petrov attributed his judgment to both his training and his intuition.

He had been told that a nuclear first strike by the Americans would come in the form of an overwhelming onslaught.

“When people start a war, they don’t start it with only five missiles,” he told The Post. “You can do little damage with just five missiles.”

Moreover, Soviet ground-based radar installations — which search for missiles rising above the horizon — did not detect an attack, although they would not have done so for several minutes after launch.

Colonel Petrov was at first praised for his calm, but in an investigation that followed, he was asked why he had failed to record everything in his logbook. “Because I had a phone in one hand and the intercom in the other, and I don’t have a third hand,” he replied.

He received a reprimand for making mistakes in his logbook.

The false alarm was apparently triggered when the satellite mistook the sun’s reflection off the tops of clouds for a missile launch. The computer program that was supposed to filter out such information had to be rewritten.

This wasn’t the last time that the world unknowingly came close to nuclear war:

In November 1983, NATO carried out Able Archer 83, a big military exercise simulating a coordinated nuclear attack. The exercise, alongside the arrival in Europe of Pershing II nuclear missiles, led some in the Soviet leadership to believe that the United States was using a cover for war; the Soviets placed air units in East Germany and Poland on alert. (Able Archer is the subject of the recent television series “Deutschland ’83.”)

Colonel Petrov retired from the military in 1984. He got a job as a senior engineer at the research institute that had created the early-warning system, but had to retire to care for his wife, Raisa, who had cancer. She died in 1997. In addition to his son, Dmitri, Colonel Petrov is survived by a daughter, Yelena.

Colonel Petrov had largely faded into obscurity — at one point he had been reduced to growing potatoes to feed himself — when the publication in 1998 of the memoir of Gen. Yuriy V. Votintsev, the retired commander of Soviet missile defense, brought to light Colonel Petrov’s role in averting nuclear Armageddon.

The book brought Colonel Petrov a measure of prominence. In 2006, he traveled to the United States to receive an award from the Association of World Citizens, and in 2013 he was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize. He was the subject of a 2014 hybrid documentary-drama, “The Man Who Saved the World.”

When I first heard about Petrov’s story several years ago, I found myself thinking about what I was doing while this was unfolding at the time. I was fifteen years old at the time and, since this apparently occurred during the morning hours in Russia, most likely have been asleep completely unaware of just how close the world had come to what could have been a truly horrific event. And we have one man to thank for averting it.

Thank you, sir, for using your brains and not your paranoia. The world still exists because people like you take the extra few seconds to *THINK* and not just react. You deserved far better then you got in this world.

Nice.

In 1979, in a similar incident, Zbignew Brzezinski received the 3 AM call that 2,000 Russian missiles were incoming and delayed notifying President Carter. WIKI has a list of eleven such close calls.

Maybe we should recognize that nukes are simply too dangerous to have around.

@gVOR08:

Nah, that would be silly! We’ve been protected by nukes for over half a century and nothing bad has ever happened. And Trump is the bestest most capablest leader for nukes we’ve ever had. And he’s got the bestest people to. He even listens to the shows so that he knows what’s going on in advance of his security briefings. We got nuthin to worry about.

@Just ‘nutha ig’nint cracker:

Ah, yes. I vividly recall Der Trumpster claiming that he knew more about ISIS than “the generals” because he watched “the shows.” Same for the nuclear arsenal and its deployment, one supposes.

Sadly, one of the biggest stories and greatest peace heroes of the last century will only be a footnote in the history books. Mr. Reagan and the Korean airliner incident all only helped to fuel a dangerous period of terrible relations that only a cool-headed Soviet military officer had the courage to prevent a nuclear war based on a glitch of radar. It didn’t seem reasonable to him that that the U.S. would only launch four missiles against the Soviet Union. To him it seemed like a radar glitch of some sort and he refused to kill millions of civilians because of what appeared to be some error.

Of course the irony of that is we probably avoided World War III precisely because of the fact that the world’s two superpowers had nuclear weapons…

May he rest in peace. I’m afraid that nowadays, our leaders would panic at any sign of something like this and launch a massive counterstrike. The results are too horrifying to contemplate, but contemplate them we must.

@SC_Birdflyte: “May he rest in peace. I’m afraid that nowadays,

our leadersTrump would panic at any sign of something like this and launch a massive counterstrike. The results are too horrifying to contemplate, but contemplate them we must.”Fixed that for you. Even when Dubya and the Chicken War Hawks were in charge, I never considered what you are saying as possible. This year, I postponed a trip to visit friends in Korea over concern that the saber rattling between Trump and Kim would get out of hand. Trump’s performance at the UN did nothing to allay my fears. Not. At. All.