Supreme Court: Police Can Take DNA Samples Before Conviction

Another body blow to the Fourth Amendment from the Supreme Court.

Ruling on a case arising out of Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled today that law enforcement can take DNA from someone once they are arrested regardless of whether they have probable cause to believe the sample will provide relevant evidence in the matter they’ve been arrested for, and without the need for a warrant:

A divided Supreme Court ruled Monday that police may take DNA samples as part of a routine arrest booking for serious crimes, narrowly upholding a Maryland law and saying the samples can be considered similar to fingerprints.

“DNA identification represents an important advance in the techniques used by law enforcement to serve legitimate police concerns for as long as there have been arrests,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote in the 5 to 4 ruling.

The decision overturned a ruling by Maryland’s highest court that the law allows unlawful searches of those arrested to see whether they can be connected to unsolved crimes. The federal government and 28 states, including Maryland, allow taking DNA samples.

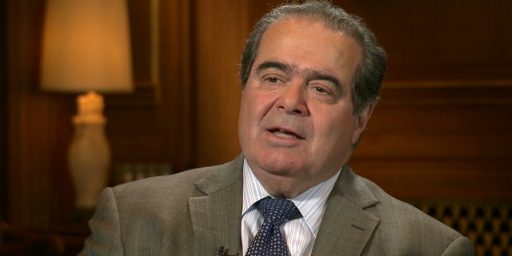

The court split in an unusual fashion. The dissenters were three of the court’s liberals, and conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who amplified his displeasure by reading a summary of his dissent from the bench.

“The court has cast aside a bedrock rule of our Fourth Amendment law: that the government may not search its citizens for evidence of crime unless there is a reasonable cause to believe that such evidence will be found,” Scalia said from the bench.

He added: “Make no mistake about it: Because of today’s decision, your DNA can be taken and entered into a national database if you are ever arrested, rightly or wrongly, and for whatever reason.”

Scalia was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Kennedy wrote that the decision was more limited than that: DNA can be taken from those suspected of “serious” crimes. He said that police have a legitimate interest in identifying the person taken into custody and that the DNA samples could make sure that a dangerous criminal is not released on bail.

Prior to today’s decision, it was generally the rule that law enforcement could only obtain DNA evidence from a suspect via a warrant signed off on by a judge, meaning that they would have to show probable cause that the evidence they seek, the suspect’s DNA, would lead to evidence of a crime. Obviously, when investigating a case where DNA evidence has already been recovered from a crime scene, such as rape and murder cases, its fairly easy to meet that burden and there’s very little that a suspect can do at that point to challenge such a warrant. What law enforcement is seeking to do here, and what the Court’s majority has allowed, is mandatory DNA testing not for the purpose of aiding in a criminal investigation (because in those cases, the police could have easily obtained a warrant) but to take that DNA evidence and test it against the growing catalog of DNA samples from unsolved crimes that have been collected in the years since DNA analysis has become a tool of law enforcement.

One can easily see the advantages that such a system might have for law enforcement. Rather than having to reopen investigations in cold cases, they can just collect DNA from everyone arrested for “serious” crimes (more about that in a bit) and test it against their databases. If there’s a match, they’ve got their man. Admittedly, there is a strong public interest in solving unsolved crimes, especially unsolved violent crimes, however that doesn’t mean that this public interest outweighs the individual liberty, Constitutional, and privacy concerns that arise out of the practice of indiscriminately taking DNA samples when people are arrested, but before they’ve been convicted. In it’s opinion, the majority, made up of Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Thomas, Justice Alito, Justice Kennedy and Justice Breyer, argues that the public interest clearly outweighs any liberty interests on the part of suspects.

As a starting point, the majority argues that the state has a substantial interest in both correctly identifying the people that are in its custody on criminal charges and in determining if they are potentially suspects in any other crimes. This part of the opinion spends much time comparing DNA testing to fingerprint analysis, and concludes that there are substantially identical. The Court then argues that the DNA test is really nothing more than another step in the proper processing of arrestees, an analysis which seems to completely ignore the fact that, in reality, the DNA test is effectively the opening, or re-opening, of a criminal investigation totally unrelated to the one for which the suspect has been placed under arrest. After doing that analysis, the Court then concludes that the liberty interests of criminal Defendants do not override the interests of the state:

By comparison to this substantial government interest and the unique effectiveness of DNA identification, the intrusion of a cheek swab to obtain a DNA sample is a minimal one. True, a significant government interest does not alone suffice to justify a search. The government interest must outweigh the degree to which the search invades an individual’s legitimate expectations of privacy. In considering those expectations in this case, however, the necessary predicate of a valid arrest for a serious offense is fundamental. “Although the underlying command of the Fourth Amendment is always that searches and seizures be reasonable, what is reasonable depends on the context within which a search takes place.” New Jersey v. T. L. O., 469 U. S. 325, 337 (1985). “[T]he legitimacy of certain privacy expectations vis-à-vis the State may depend upon the individual’s legal relationship with the State.” Vernonia School Dist. 47J, 515 U. S., at 654.

The reasonableness of any search must be considered in the context of the person’s legitimate expectations of privacy. For example, when weighing the invasiveness of urinalysis of high school athletes, the Court noted that “[l]egitimate privacy expectations are even less with regard to student athletes. . . . Public school locker rooms, the usual sites for these activities, are not notable for the privacy they afford.” Id., 657. Likewise, the Court has used a context-specific benchmark inapplicable to the public at large when “the expectations of privacy of covered employees are diminished by reason of their participation in an industry that is regulated pervasively,” Skinner, 489 U. S., at 627, or when “the ‘operational realities of the workplace’ may render entirely reasonable certain work-related intrusions by supervisors and co-workers that might be viewed as unreasonable in other contexts,” Von Raab, 489 U. S., at 671.

The expectations of privacy of an individual taken into police custody “necessarily [are] of a diminished scope.” Bell, 441 U. S., at 557. “[B]oth the person and the property in his immediate possession may be searched at the station house.” United States v. Edwards, 415 U. S. 800, 803 (1974). A search of the detainee’s person when he is booked into custody may ” ‘involve a relatively extensive exploration,'” Robinson, 414 U. S., at 227, including “requir[ing] at least some detainees to lift their genitals or cough in a squatting position,” Florence, 566 U. S., at ___(slip op., at 13).

(…)

In light of the context of a valid arrest supported by probable cause respondent’s expectations of privacy were not offended by the minor intrusion of a brief swab of his cheeks. By contrast, that same context of arrest gives rise to significant state interests in identifying respondent not only so that the proper name can be attached to his charges but also so that the criminal justice system can make informed decisions concerning pretrial custody. Upon these considerations the Court concludes that DNA identification of arrestees is a reasonable search that can be considered part of a routine booking procedure. When officers make an arrest supported by probable cause to hold for a serious offense and they bring the suspect to the station to be detained in custody, taking and analyzing a cheek swab of the arrestee’s DNA is, like fingerprinting and photographing, a legitimate police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.

The Court’s opinion was roundly rejected by a dissenting group of four Justices that included Justice Ginsburg, Justice Sotomayor, Justice Kagan, and, in what is likely to be a surprise to many Justice Scalia, who wrote one of his trademark scathing dissents in defense of the 4th Amendment:

No matter the degree of invasiveness, suspicionless searches matter the degree of invasiveness, suspicionless searches are never allowed if their principal end is ordinary crimesolving. A search incident to arrest either serves other ends (such as officer safety, in a search for weapons) or is not suspicionless (as when there is reason to believe

the arrestee possesses evidence relevant to the crime of arrest)(…)

That taking DNA samples from arrestees has nothing to do with identifying them is confirmed not just by actual practice (which the Court ignores) but by the enabling statute itself (which the Court also ignores). The Maryland Act at issue has a secon helpfully entitled “Purpose of collecting and testing DNA samples.” Md. Pub. Saf. Code Ann. §2-505. (One would expect such a section to play a somewhat larger role in the Court’s analysis of the Act’s purpose—which is to say, at least some role.) That provision lists five purposes for which DNA samples may be tested. By this point, it will not surprise the reader to learn that the Court’s imagined purpose is not among them.

Instead, the law provides that DNA samples are collected and tested, as a matter of Maryland law, “as part of an official investigation into a crime.” §2-505(a)(2). (Or, as our suspicionless-search cases would put it: for ordinary law-enforcement purposes.) That is certainly how everyone has always understood the Maryland Act until today. The Governor of Maryland, in commenting on our decision to hear this case, said that he was glad, because ”[a]llowing law enforcement to collect DNA samples . . . is absolutely critical to our efforts to continue driving down crime,” and “bolsters our efforts to resolve open investigations and bring them to a resolution.” Marbella, Supreme Court Will Review Md. DNA Law, Baltimore Sun, Nov. 10 2012, pp. 1, 14. The attorney general of Maryland remarked that he “look[ed] forward to the opportunity to defend this important crime-fighting tool,” and praised the DNA database for helping to “bring to justice violent perpetrators.” Ibid. Even this Court’s order staying the decision below states that the statute “provides a valuable tool for investigating unsolved crimes and thereby helping to remove violent offenders from the general population”— with, unsurprisingly, no mention of identity. 567 U. S. ___, ___ (2012) (ROBERTS, C. J., in chambers) (slip op.,at 3).

More devastating still for the Court’s “identification” theory, the statute does enumerate two instances in which a DNA sample may be tested for the purpose of identification: “to help identify human remains,” §2-505(a)(3) (emphasis added), and “to help identify missing individuals,” §2-505(a)(4) (emphasis added). No mention of identifying arrestees. Inclusio unius est exclusio alterius. And note again that Maryland forbids using DNA records “for any purposes other than those specified”—it is actually a crime to do so. §2-505(b)(2).

The Maryland regulations implementing the Act confirm what is now monotonously obvious: These DNA searches have nothing to do with identification

Scalia presents a considerable amount o time picking apart the majority’s attempt to analogize DNA testing to standard police booking procedures such as photographs and fingerprinting. As Scalia notes, the differences are made most apparent by the amount of time that it typically takes to analyze a DNA sample and compare it to the existing database, a factor which reinforces the idea that the Maryland law is aimed not at aiding in the identification of a suspect who has been arrested but at going on what is essentially the proverbial “fishing expedition” to see if the arrestee, who again is innocent until proven guilty of the charges he was arrested for, may have culpability for other crimes. That’s roughly analogous to police saying that they’re going to search someone’s home sua sponte without a warrant to see if there might be evidence of other crimes there, which would clearly be impermissible. If that’s impermissible, though, it’s hard to see how suspicionless, warrentless, DNA testing can possible be permissible under a proper understanding of the Fourth Amendment.

As the dissent goes on to note, the majority argues that its holding in today’s opinion is limited because the statute in question only applies to “serious” crimes, however that might be defined, however that limitation is not likely to last very long:

The Court disguises the vast (and scary) scope of its holding by promising a limitation it cannot deliver. The Court repeatedly says that DNA testing, and entry into a national DNA registry, will not befall thee and me, dear reader, but only those arrested for “serious offense[s].” Ante, at 28; see also ante, at 1, 9, 14, 17, 22, 23, 24 (repeatedly limiting the analysis to “serious offenses”). I cannot imagine what principle could possibly justify this limitation, and the Court does not attempt to suggest any. If one believes that DNA will “identify” someone arrested for assault, he must believe that it will “identify” someone arrested for a traffic offense. This Court does not base its judgments on senseless distinctions. At the end of the day, logic will out. When there comes before us the taking of DNA from an arrestee for a traffic violation, the Court will predictably (and quite rightly) say, “We can find no significant difference between this case and King.” Make no mistake about it: As an entirely predictable consequence of today’s decision, your DNA can be taken and entered into a national DNA database if you are ever -arrested, rightly or wrongly, and for whatever reason.

The most regrettable aspect of the suspicionless search that occurred here is that it proved to be quite unnecessary. All parties concede that it would have been entirely permissible, as far as the Fourth Amendment is concerned, for Maryland to take a sample of King’s DNA as a consequence of his conviction for second-degree assault. So the ironic result of the Court’s error is this: The only arrestees to whom the outcome here will ever make a difference are those who have been acquitted of the crime of arrest (so that their DNA could not have been taken upon conviction). In other words, this Act manages to burden uniquely the sole group for whom the Fourth Amendment’s protections ought to be most jealously guarded: people who are innocent of the State’s accusations

Scalia is absolutely right here, of course. Trying to argue that the power to engage in suspicionless DNA testing incident to arrest only in the case of “serious” crimes — something that never really gets defined in the majority opinion is, in the end, a waste of time. Given the logic of the majority’s opinion, it is virtually inevitable that DNA swabbing of arrestees will be extended beyond “serious” crimes, and indeed beyond felonies and into misdemeanors like the traffic offenses that Scalia mentions. For example, everyone who is arrested on a DUI charge is arrested and taken into custody. How long is it going to be before all those people are also subject to DNA swabbing? As the dissent notes, some 23,000,000 people will be arrested or one reason or another before their mid-20s. In many cases, they will be completely innocent of the charges they are arrested for. Under the Court’s logic, every single one of these people will now be required to give up a DNA sample regardless of whether there was probable cause to ask for such evidence or not. As Scalia said, the very people the Fourth Amendment is supposed to protect have just had their Fourth Amendment rights seriously curtailed.

As Scalia notes at the end of his dissent, one can only hope that the Court will see the error of its ways and reverse itself in a future case.

Here’s the opinion:

For once, I agree with Scalia. I better buy a lottery ticket today.

Thank God conservatives are reigning in an out of control government.

@anjin-san: Scalia is a voice in the conservative wilderness on this one, for sure.

Then again, there’s nothing about the government of Maryland that qualifies as conservative, least of all Governor O’Malley.

this coming from a state that suspends kids for bringing a cap gun to school and interrogates them without the presence of parents.

I’m actually not all that surprised that Scalia ruled as he did. Scalia has been slowly moving towards a more robust 4th amendment (the Jardines case earlier this year, U.S. v Jones last year about GPS devices). I’m really disappoint in Breyer, between the dog sniff cases and this one, he seems to be in favor of neutering the 4th amendment more than it already is, and is choosing to ally himself with the right wing of the court in doing so.

@DC Loser: Seems to me they want to pull the kid’s DNA, too. Then they can swab the cookie jar to see if he’s been filching the Chips Ahoy.

This is truly a bizarre set of dissenters. Has there ever been another case where Justices Scalia and Ginsburg voted the same way and been in the dissent? I would have expected that if they both believed something, it was pretty clearly well settled constitutional law.

Also, this is the case where Thomas breaks his pattern of voting with Scalia? Eesh.

Also, too, I eagerly await some pundit to notice that all the women dissented, plus Scalia, and try to explain why, in this instance, Scalia is voting like a woman. I bet it has something to do with the hats.

Scalia, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Ginsburg…I’ll be sure to buy all their records from now on.

I was somewhat persuaded by the argument that DNA is like fingerprints, needed for ID. Then I realized that while it makes sense to take fingerprints for future identification of the subject, once they have the fingerprints the DNA is redundant and the ID argument is specious.

@gVOR08: Not to mention the potential for DNA to tell a whole lot more about you than fingerprints ever could.

Amazing. A gun registry equals tyranny of the highest order. A national database of citizens’ DNA? No problem.

@gVOR08:

I also buy the fingerprint analogy. Way back when, people believed fingerprints were good, as good as we now think DNA is. They collected fingerprints at booking and tried to match them to past crimes. Once fingerprints became digitized and searching on a national scale became possible, this accelerated. It might have been one thing if people had yelled “stop” then.

But given the fingerprint precedent, using DNA for matching to past crimes seems no more intrusive.

If we want to yell “stop” now, it would be before cops start looking for “risk factors” like say a genetic bias towards violence.

@gVOR08:

And THEN you realize, DNA is NOT specious. That HUNDREDS of people have been cleared of crimes because of DNA.

Really, Reality? Meet Science. It’s a bitch. The finger print/DNA analogy cinched it for me.

@OzarkHillbilly:

That’s the other scandal, that the government won’t spend money on DNA tests to clear, and funds must be raised by friends, family, or charities.

Setting aside the Constituional arguments for a moment, I am curious as a practical matter as to what the liberty interest at stake is here. Unlike some other areas of the first amendment, such entering and searching a home or car, this procedure seems relatively painless (swabbing a cheek). Is it the simple physical act that most are concerned about, or is there something affirmatively nefarious that could be done with that DNA that people are concerned about?

It seems as if (beyond the initial cheek swab), the process is one of elimination, rather than a risk of some affirmative negative act.

I understand that personal affront and the issue of innocent and proven guilty and all of that, but I am wondering if there is some way that the DNA evidence could be used in a harmful way that concerns people. Just trying to consider the balance of harms here and see if I am missing something.

@john personna: Finger prints cannot be put at a crime scene from anyone but the perp, DNA can be.

@barbintheboonies:

Actually I see that they can, but you know … plausible scenarios.

I’m with Scalia. The ‘fishing’ argument is probably the thing that cinches it for me, but there’s additional problems with harassing innocent people. One of the arguments brought up on slashdot was that you can glean a lot of medical information from DNA, and there are most certainly laws about keeping medical records private.

Oh, and unless something has changed recently, DNA testing is far from perfect. Imagine getting arrested for no reason only to find yourself charged with a bunch of crimes committed by somebody whose DNA “matches” yours. Think that’s a one in a billion chance? IIRC, it’s something more like one in a thousand, depending on various factors. DNA is really only useful for proving innocence, not guilt.

What is the limit for these DNA matches. Is it possible that a family member is arrested and their DNA is close enough to one in a cold case, can they then go after the arrested person”s entire family? This seems like a slippery slope until everyone’s DNA is taken and kept indefinitely. England’s DNA samples are only kept a finite amount of time after an arrest, 5 years I believe, which they recently got caught violating. This makes me a bit uncomfortable because there is seemingly no limit to the fishing expeditions the police can use, especially if the DNA sample isn’t removed from a database after X number of years.

Why don’t they just come out and demand DNA from everyone and get it over with?

@Dave D:

Why would that be bad? You said “go after,” but let’s use the “investigate” word instead.

Don’t we want cold cases solved?

@DC Loser:

Funny that the limit on fingerprints was that we give 1 for a driver’s license. Somewhat … partial.

@john personna: I think Dave D’s question was regarding the degree. More like, “say the DNA implicates anyone up to a 6th cousin of the person arrested, does that mean the police can go search hundreds of people’s houses?”. As opposed to, “the DNA implicated the person arrested or his two sisters.”

Which, by the way, I don’t believe DNA can reliably do.

@Franklin:

That’s the thing, you have to string together other dubious legal arguments to make the family match scary. You need warrants to search houses. Are you suggesting that judges would grant warrants on all family members?

If you don’t believe DNA can reliably associate 6th cousins, you shouldn’t fault the DNA test, you should demand that investigations are commensurate with the confidence of the test.

For a 10 year old rape and murder, maybe you should interview family members to see if they were even in town in that time frame, and then if any freak out in the interview.

@john personna:

They don’t need a warrant anymore. The cops trump up some charge, arrest the family member(s), take a cheek swab, then “Oh, sorry, our mistake, you may go.”

@Mikey:

@john personna: I must have misunderstood you, I thought you were still talking about DNA rather than searching the house. You’re right about the latter, of course.

@john personna: If you want to use the word investigate then perhaps the police should investigate as opposed to using DNA to dragnet every and any possible crime that remains unsolved.