Supreme Court Rules Only U.S. Arrests Matter

Justices Side With Gun Owner Who Concealed Arrest in Japan (NYT | RSS)

When Gary Small walked into a sports store in his hometown of Delmont, Pa., to buy a pistol, he probably did not see himself as the central figure in a Supreme Court case. But that is what he became. Before walking out of the store with his 9-millimeter pistol on June 2, 1998, he filled out the mandatory federal form. It asked whether he had ever been convicted “in any court” of a crime punishable by a year or more in prison. Fatefully, he answered “no.”

In fact, Mr. Small had never been convicted of any crime – in the United States. He had, however, run afoul of the law in Japan. The Customs authorities there became suspicious of him in 1992, when he shipped three electric water heaters from the United States to Japan, supposedly as gifts. When he picked up the third water heater at the Okinawa airport, the authorities opened it and found two rifles, eight pistols and more than 400 rounds of ammunition, according to court papers. Mr. Small was convicted in Japan in 1994 of smuggling guns and sentenced to five years in prison there. Paroled in the spring of 1998, he returned to the United States and his rendezvous with legal history.

[…]

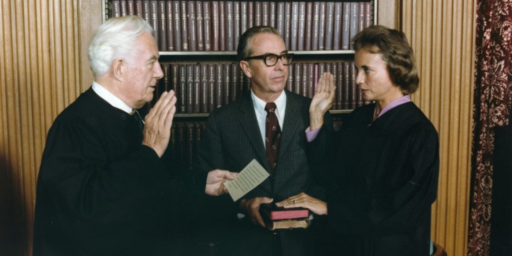

A federal district court rejected his argument, and Mr. Small entered a conditional plea of guilty, receiving an eight-month sentence but remaining free on bail while he appealed the district’s court’s refusal to dismiss the charge. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, based in Philadelphia, agreed with the district court. But today, the Supreme Court sided with Mr. Small, ruling 5 to 3 that the phrase “convicted in any court” applies only to convictions in the United States. “Congress ordinarily intends its statutes to have domestic, not extraterritorial, application,” Justice Stephen G. Breyer wrote for a majority that also included Justices John Paul Stevens, Sandra Day O’Connor, David H. Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

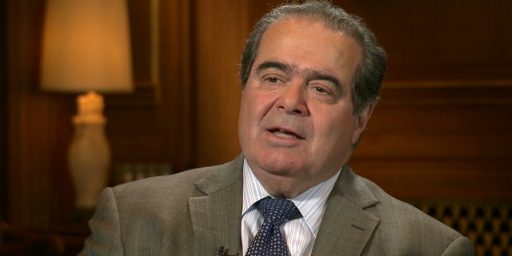

To include foreign convictions, the majority reasoned, would raise the possibility of tainting a person who had been caught up in a legal system lacking American standards of fairness. Singapore imprisons people for up to three years for vandalism, the majority noted by way of example. In dissent, Justices Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia and Anthony M. Kennedy said, among other things, that “any” means what it says. “Indisputably, Small was convicted in a Japanese court of crimes punishable by a prison term exceeding one year,” Justice Thomas wrote. “The clear terms of the statute prohibit him from possessing a gun in the United States.”

For once, I’m in agreement with Stevens and disagree with Thomas and Scalia. The idea that one would have to disclose convinctions in foreign courts is simply mindboggling. That the Justices who rail against the use of international judicial precedent see it differently is rather stunning, too.

As an aside, I should note that Chief Justice Rehnquist did not participate in the voting. Given his poor health of late, that can’t be a good sign.

Update: Apropos the above, the Washington Times coverage of the forum featuring Scalia, O’Connor, and Breyer last week is particularly instructive.

Justices argue international law (Apr. 24)

Supreme Court Justices Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor and Stephen G. Breyer clashed last week over the role of international law and foreign judges at a rare group discussion in Washington. At the forum, broadcast on C-SPAN television last week, Justice Breyer appeared the most sympathetic to justices citing international law and foreign court decisions, saying the high court is faced with “more and more cases” in which the laws of other countries are relevant. “Where there is disagreement is how to use the law of other nations where we have some of those very open-ended interpretations of the word ‘liberty’ or ‘cruel and unusual punishment,'” he said. “It’s appropriate in some instances to look to how other courts might have decided similar issues,” although laws of other countries “do not bind us by any means.”

Justice Scalia said “foreign law is totally irrelevant” on most issues, such as the original meaning of the Constitution or what Americans now see as fundamental rights. “It doesn’t show what the Constitution originally meant, and it doesn’t show what is fundamentally important to Americans today,” he said. “It shows what’s fundamentally important to somebody else today.”

Justice O’Connor, in her first public remarks on the issue, called the debate over the role of foreign law “much ado about nothing.” “There are areas where we look to foreign law to interpret treaties that other nations and we have joined,” she said. “Of course we look to foreign law.” Although it may not help to consult foreign law in interpreting the meaning of the First Amendment, she said, it does not hurt to be aware of what other countries have done when weighing such evolving concepts as “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Amusingly, Breyer wrote the opinion for the Court saying that international convictions are irrelevant, with O’Connor joining. Scalia dissented, even though he thinks foreign opinions worthless.

Now, granted, convictions in foreign courts are somewhat different from the judicial philosophy of overseas judges. Still, my position is at least consistent: Neither should have any bearing in American law. Even with respect to treaties, all that’s relevant is the text of the treaty and the debate that took place in the U.S. Senate. The rest is perhaps interesting from an intellectual view but irrelevant from a judicial standpoint.

His nonparticipation doesn’t indicate recent health trouble; this case was heard months ago. Either you’re on the case from the ground up, or you’re out, is how they do it. He can’t show up late like Voinovich & say “hey, doesn’t sound good to me.”

And I’m glad you too were amused that opinions on international law are so … flexible. (On both sides, let’s note.)

Rehnquist had made it pretty clear that he wouldn’t participate in decisions unless he was needed as a tiebreaker. That’s why his name wont come up this session unless we’re looking at a 5-4 decision.

Doesn’t it make sense, though, that as judges committed to strict interpretations of the text both Scalia and Thomas would decide this way?

Scalia has often said that his rulings don’t reflect his preferences, but that he’s bound by the actual dictionary meaning of the words in the law in question. So while he’s not one to bring international law into the equation, his ruling here is consistent with his judicial philosophy since his point rests on the meaning of the word “any”.

I don’t agree with him either (and as a lefty rarely do), but his decision does reflect his commitment to base decisions solely on the text of the law, precedent, and the text of the Constitution.

Kathy: I suppose on could make a “plain meaning” argument that “any court” is ANY court. But, surely, a reasonable interpretation of that would be any court OVER WHICH THE LEGISLATURE HAS JURISDICTION. When filling out insurance paperwork, I wouldn’t expect people to list speeding tickets they got in Germany.

The idea that one would have to disclose convinctions in foreign courts is simply mindboggling.

So, you don’t think we should be required to disclose, say, serious drug convictions? How about terror-related ones?

I don’t believe that even YOU believe what you wrote.

Well this is an issue Congress should address. Convictions in foreign courts for crimes that are punishable here and/or are serious indications of criminality should be grounds for preventing the purchase of a weapon. We ought not consider all foreign convictions as the grounds for conviction are not vetted by our court systems, but certainly we should take them to account.

James, I think the point is, that their should be felonies that happened in other countries that should count here, if the are serious enough.

Consider the one you quoted, an American smuggling illegal weapons to Japan (don’t know their weapon laws). What if it was to Britian with their strick no-gun laws? What if he was caught smuggling an anti-tank weapon?

Now he’s still American, no contention, but he gets to still purchase weapons in the USA even though he’s still a convicted gunrunner?

Sure it’s one thing to smuggle weapons overseas to our neighbors but he can purchase weapons here in the USA? What’s going to stop him from dealing those weapons illegally here in the US? He’s willing to deal them illegally in a foreign country, what’s to stop him from dealing with the local (insert gang here).

I think that the issue needs to be looked at closer. Yes speeding tickets overseas, BFD, murder, rape, weapon charges (as this case) need to be evaluated by a country+charge basis I think.

It’s not at all mindboggling. Scalia’s objection to the invocation of foreign law as precedent is limited to the COURT citing foreign law as a justification for its decisions.

Congress, however, is free to say that foreign convictions shall be disclosed or even that foreign law shall be relevant. Scalia’s objections to foreign law is that ABSENT such a Congressional requirement, the Courts must not raise the issue on their own.

Here, the argument is that by phrasing the federal form as requiring “any” convictions–that Congress was rendering foreign convictions/law relevant. That is their right to do. The plain language of the form makes no distinction between US courts or foreign courts.

Now, whether Congress makes a distinction between the preclusive effect of a foreign conviction vs a US conviction is a separate matter that isn’t implicated here. But Scalia’s position is not inconsistent at all.

Nice distinction, Mr. Cross, though I still think it’s a good decision. The majority was justified in supposing that Congress expressed no intent to consider foreign convictions. Hammering on a literal reading of “any” is an uphill battle.

While I haven’t read the opinion, I don’t think that the majority’s opinion is unreasonable. The given (partial) justification that laws GENERALLY aren’t intended to have extraterritorial effect is certainly true. But where the law uses such universal language as “any court”–and given the purpose of the law/Congress to prevent felons from acquiring firearms, then it seems more reasonable that they meant any and all felony convictions.

If the guy had been convicted of murder in Germany, does it make sense that Congress’ law would NOT want to know that fact? That’s a tough one to buy.

The proper analysis would be that the law req’s you to disclose all such convictions, regardless of country. If you are then denied a gun based on that conviction, then you should be able to challenge that denial and THEN we can get into to what effect Congress sought the law to have re: foreign convictions.

But based on the language of the law (“any”) and its clear purpose (no guns for felons)–Scalia’s position strikes me as the more reasonable.

This discussion illustrates the degree that the activist view has

become part of the mainstream.

Whether you believe that foreign convictions should disqualify

you or not isn’t the issue that the supreme court should be

considering.

The issue is whether the law is unconstitutional or not. I don’t see why the law would be unconstitutional.

I think that it’s a dumb law for exactly the reasons stated but that means that the legislature should re-word the requirement. It doesn’t mean that the supremes should become the legislature.

You can think the law is dumb and still find it disturbing that the supremes overturn it.

Really! If the State of Arizona makes you fill out a form asking if you’ve ever been convicted of a felony in any court, can you answer “no” if you’ve convicted of four felonies in California, three in Nevada, two in Utah, one in New Mexico, but none in Arizona? I don’t think so.

The only thing I find odd about this decision is Justice O’Connor’s position, which appears to be that foreign courts are super-duper world courts when it comes to deciding what our own Constitution means, yet are not even worthy to be called “courts” at all when interpreting a plainly worded statute.

“Now he’s still American, no contention, but he gets to still purchase weapons in the USA even though he’s still a convicted gunrunner?”

Suppose the was convicted in Nicaragua of running guns to the Contras? While I think that would be just as bad, many would hail him as a “freedom fighter.”

I think what we all would like is along the lines of “crimes committed in countries whose judicial system we trust and actions that are also crimes here.” I have no idea how would write a law to do that, let alone put it on a form in an understandable way. The closest I can come to is “countries with which we have extradition treaties”

The argument that “any” means “any” presupposes that an examination of Congressional intent is unnecessary because of the “plain meaning” of the word. As a rule, examination of legislative intent is usually reserved for instances where the language at issue is patently ambiguous. In such a case, the court would examine other instances where the word “any” has appeared in federal statutes. It seems to me (on shallow assessment) that the ambiguity of “any” is latent (if it is ambiguous at all), but there are good reasons for going further with the analysis anyway.

The problem with observing laws of other countries that are consistent with our own is that it doesn’t take into account the presence or lack of procedural due process that is the hallmark (some would say albatross) of our system. As an extreme example, would we observe the law of some muslim countries where trials are perfunctory and hands are lopped off for theft. Theft is theft?

But we could not apply “any” in such flexible fashion, weighing the laws and procedures of the country where the crime is committed before determining whether “any” should count.

Clarence, Thomas and Kennedy, by taking their positions, demonstrated complete lack of statehood vision. I think the problems are obvious. Does Japan even have felonies? maybe they call them something else. Soliciting prostitution in most countries is legal. If arrested in the States, could a solicitor argue ” well, its legal in Japan “…Until the globe in under one set of agreed laws, the US is the US and Japan is Japan.

Interesting post James.

Wavemaker,

The dissent engages in just such an analysis and notes that the law does make distinctions elsewhere between the application of Federal v. State law. This particular provision was the only one that eschewed any sort of limiting language and used the all-inclusive “any.”

As for the objection that other countries’ laws don’t have the same DP rights, etc etc. Dissent covers that too. On the whole, convictions which result in imprisonment for more than one year (which are the convictions you need to disclose) DO track fairly well with the sorts of crimes that result in similar prison terms here. Moreover, the crimes that don’t track are so few and far between (opinion lists about 10 such denials over the years) to undercut it’s own argument that requiring disclosure would lead to this disproportionate impact.

Again, if one is imprisoned for 3 years in Singapore for jaywalking, that should be disclosed and THEN, if the application for a gun is denied, you can argue that as applied to that case, the denial is improper in light of the legislation.

But to foreclose on the ENTIRE body of evidence that exists keeping “foreign” criminals away from weaponry seems to flout what Congress wrote.

Again, it all ultimately boils down to what Congress said.

The same logic ought to apply to tax law as it did in the gun law case.The same day the Small case was handed down, so was the Pasquantino case, which was basically a wire fraud case.In the Small case, the gov’t will not deny a citizen gun ownership because of a criminal conviction abroad- but said in Pasquantino, the same day- that they may prosecute someone for alledgely plotting to cheat a foreign gov’t out of tax revenue. These twin rulings shed indirect light on the justices views of the interaction between U.S. and foreign law, which is a very important issue that needs to be addressed by Congress soon Whoever thinks there will be no conflicts internationally is dead wrong (Justice Thomas). The courts have been tangled up in internal debate over the applicability of foreign court rulings for far too long. Pasquantino lost their case by one vote, that vote being Chief Justice Rehnquist who not present at oral argument due to his illness in November. It was the only case that was a 4-4 deadlock in the November sitting making the Chief be the one to make the deciding vote. If you look at all of the ramifcations this conviction will have internationally, it is a very scary thought. As someone has recently quoted: If Robert Mugabe decided to confiscate your property and you try to flee Zimbabwe with some of it, does that become wire fraud?? Does this mean every stripe-lawyer, broker, insurance agent, account, fiduciary might be forced to ensure that their clients comply not only with U.S. laws, but also with the laws of all nations? If clients don’t, advisors themselves might be prosecuted. Many were fearing that the Pasquantino case would be upheld and now it has been.This just doesnt sound like a good thing. Fact is: personal interpreation of the law is not what these justices should be doing.It is unconstitutional. THIS IS WRONG AND INJUST any way you look at it. So what the high court is saying is its okay for someone to possess a firearm in US if a felons conviction was by a foreign gov’t but if someone who alledgedly smuggled alcohol to Canada and paid all U.S taxes,they can be prosecuted in the U.S. WHY?? Because they owe Canada tax money??? I will say it again-The same logic ought to apply to tax law as it did in the gun law case. Its terrible that our Supreme Court Justices are so undecided what to do when it comes to reading foreign tax laws. How about restitution which is mandatory in such a case? Nope, gov’t couldn’t do that either, because any money that would have been owed would be to Canada.Is the U.S. gov’t now in the business of collecting Canadian’s taxes for them too?? If anyone cares, this was my father who was convicted and because of one vote and Justice Thomas’ view of the word “any” I will live each day without my father for 5 years. I may not be as powerful as the Supreme Court Justices, but I promise I will be doing everything in MY POWER to look to Congress to change the law.