Tax Rates of the Rich and Famous

Jon Henke is dubious of Warren Buffett’s oft-repeated claim that his $46 million annual income is taxed at 17.7 percent whereas his employees pay an average of 32.9 percent. Jon looks at the numbers and concludes, “Buffett is either paying his staff millions apiece, or they’re getting very bad tax advice.”

My guess is that Buffett is including payroll taxes for Social Security into the calculation, skewing the numbers. We currently only collect FICA on the first $90,000 of income. My guess is that almost all of Buffett’s employees, therefore, pay FICA on all their income whereas $45,910,000 of Buffett’s salary is FICA tax-free.

Whether including FICA in the category of “taxes” for this comparison is reasonable is debatable. Certainly, it looks and feels like a tax. On the other hand, it is, theoretically at least, a retirement savings account whereby people are coerced to pay in and then receive a fixed stipend upon retirement or disability. Given that people who make $90,000 a year and those who make $46,000,000 a year will receive the exact same monthly payout, it stands to reason that they should pay in the same amount.

UPDATE: Henke notes in the comments that his own calculations were based on Tax Policy Center statistics, which include all federal taxes, including FICA.

1) Buffett is almost certainly including FICA taxes in his calculation. If you don’t, it’s almost impossible to get his numbers. If you do, it’s actually quite easy.

2) I hope I’m not the only one who sees the irony in calling FICA a form of “retirement savings” in regards to employees of Berkshire Hathaway. I’m not saying you can’t make the case, but you have to admit that it’s pretty funny in this context.

Anyone who doesn’t include FICA in a discussion of tax rates is a dishonest fraud.

Buffett arranges so that virtually all of his income is in the form of capital gains that are taxed at a 15% rate. He is paid $100,000 in salary that is subject to individual income tax and FICA. But this out of $24 million is insignificant so that the above discussion is irrelevant. Figure it out yourself — $100,000 at 32%, $90,000 at 7.5% and $23,900,000 at 15%. This actually works out to be 15.1%.

He probably gets some fringe benefits like use of the corporate aircraft that he has to pay taxes on to tax on at a 32% rate that takes his total taxes up to 15.7%.

That’s a fair point. I’m not sure why that income shouldn’t be taxed at the same rate as any other, providing that it wasn’t already previously taxed as income.

No, James. If you follow the link to the total effective federal tax rates, you’ll see that the rates include “all” federal taxes.

Payroll taxes are included, as are wages, dividends, and realized capital gains.

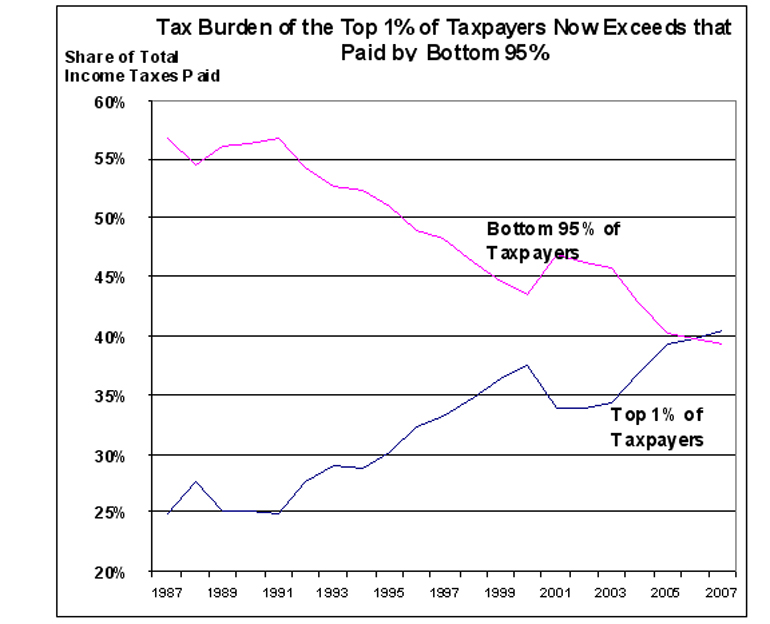

Even with all of that included, the Tax Foundation (Urban Institute and Brookings) says the top 1% of all taxpayers pays a lower total federal tax rate than he claims is “average” for his staff.

What does this mean?

Are you sure John? I looked at the link and while it mentions Social Security it appears to do so in terms of income.

However, even if it isn’t counted I can’t imagine it would move a person’s federal obligation from say 18% to 32%, that is just a pure load of bravo sierra–i.e. Buffet is lying.

Just making a distinction between whether the stocks were purchased with pre-tax or post-tax dollars.

It gives a separate account of effective tax rates for “social insurance taxes” (i.e., payroll taxes) for each quintile and the top percentages.

It also gives the cumulative effective federal tax rates, which include that and other taxes.

Andy,

Quite a bit of “unearned income” is taxed under corporate profits, then gets taxed again as income.

Why shouldn’t it be?

I think there is a structural error in the Tax Policy Center’s formulas in the link provided. By including deferred and untaxed income (e.g. 401-K contributions) as pretax income, they have decreased the relative percentage of taxes paid, even though an undetermined tax liability still exists on those funds when they are ultimately withdrawn. I believe it would be more correct to exclude any deferred and untaxed income from the pretax income sum to give a tax percentage result that is more accurate. Otherwise, year to year comparisons would be meaningless as the same funds would be counted twice as pretax income (once when earned and once when distributed) though only actually taxed once.

It violates the notion of vertical equity.

It violates the notion of vertical equity.

By…?

By taxing the same income in different ways. If a pension plan has an investment in a firm that pays a dividend and puts that money back into its investments, then it would likely be treated differently than the dividend paid to the idividual stock holder who takes the money, even if he fully intended to re-invest it say at a later date. Basically it causes distortions in how various entities in the economy behave and has two tax wedges (deadweight losses) instead of one.