Texas Man Held In Prison For Thirty-Three Years Despite Lack Of A Legal Sentence

The very definition of a miscarriage of justice.

A man in Texas has sat in prison for the past thirty-three years despite the fact that there is no valid sentence against him:

The life sentence given to a Texas man who has remained in prison for 33 years since being pulled off of death row isn’t valid, Texas’ highest criminal court said Wednesday, possibly paving the way for a new trial or the inmate’s release.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals said once it overturned Jerry Hartfield’s murder conviction in 1980 for the killing of a bus station worker four years earlier, there was no longer a death sentence for then-Gov. Mark White to commute.

The opinion was given in response to a rare formal request by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to confirm the validity of its ruling overturning Hartfield’s conviction, in light of the governor’s 1983 commutation. The New Orleans-based federal court made the request, which upheld a lower state court’s ruling that the sentence was invalid.

“The status of the judgment of conviction is that (Hartfield) is under no conviction or sentence,” Judge Lawrence Meyers wrote in a decision supported by the court’s other eight judges. “Because there was no longer a death sentence to commute, the governor’s order had no effect.”

At that point, of course, Hartfield should have been released or he should have been retried for the crime of which he was accused. Instead, he stayed in the system for another thirty-three years for no valid legal reason:

Hartfield, now 57, was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1976 robbery and killing of a Southeast Texas bus station employee. The criminal appeals court overturned his murder conviction, ruling that a potential juror improperly was dismissed after expressing reservations about the death penalty.

White commuted Hartfield’s sentence in 1983 at the recommendation of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, and he has remained in prison since then, unaware until a few years ago that his case was in legal limbo. Court documents in his case described him as an illiterate 5th-grade dropout with in IQ of 51, although Hartfield says he’s learned to read and write while in prison.

In its failed appeal to the 5th Circuit, the state argued that Hartfield’s life sentence should stand because he missed a one-year window in which to appeal aspects of his case.

Neither the prosecutor’s office in Bay City nor Hartfield’s attorney, Kenneth R. Hawk II, immediately responded to phone messages Wednesday seeking comment.

During a prison interview last year, Hartfield told The Associated Press that he’s innocent, but that he doesn’t hold a grudge about his predicament, which his lawyer last year described as “one-in-a-million.”

Since I don’t know anything at all about the facts of Hartfield’s case, I’m not going to comment on his guilt or innocence, other than to suggest that if it’s true that his IQ really is as low as 51, then there may well have been defenses that could have been raised at trial that his attorney, who I am going to assume was court-appointed either didn’t bother or didn’t care to raise. I also don’t know if they attorney who handled his trial was the same one who handled his appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeals, but whoever that person might have been, they failed in their task quite shockingly by apparently failing to ensure that there was any follow up to the Court’s decision vacating his sentence. Under the law, that should have led to either his immediate release, or a decision by prosecutors to retry the case. Neither of those things happened, and Hartfield, obviously either unaware or uninformed of his fate in the highest Court in Texas for criminal appeals, simply went on living his life day by day by day as a prisoner of the Lone Star State even though the state had no actual legal authority to hold him. To call it Kafkaesque would be an exaggeration, for I doubt even Kafka could come up with a tale this bizarre. It is, perhaps, a cross between Kafka and Joseph Heller’s great satire Catch-22. Only in this case, it involved an actual human being and not fictional characters

Notwithstanding Hartfield’s generous comments about his trial counsel, it’s clear that he was the victim of clearly ineffective counsel both at trial and on appeal. Absent a decision by prosecutors to retry him and a bail hearing, he ought to have been released from prison the day the order of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals became final. Instead, he somehow languished around for another three years when his case came to the attention of the then-sitting Governor who, obviously thinking he was being merciful, commuted a sentence that didn’t exist anymore. Hartfield then spent the next three decades in the Texas prison system even though they had no legal authority to hold him. Does anyone really think his case is anomaly?

Texas prosecutors are saying that they plan to retry Hartfield for the murder that he was originally convicted of way back when. That is their right, of course. Murder is a crime that has no statute of limitations and it does not appear that the original dismissal of his death sentence was “with prejudice,” which would mean that he could not be tried again on the same charges. However, after the passage of thirty three years of time, I have to wonder how fresh the evidence in this case is going to be and how easy it’s going to be for either the prosecution or the defense to procure witnesses who may have died or forgotten their testimony. Above all, I would hope that Mr. Hartfield will have far more competent counsel than he did when he was convicted back when I was still in grade school. In addition, if he does end up being rightfully convicted in a second trial, one would hope that whatever sentence is imposed on Hartfield includes credit for the time he was wrongfully imprisoned.

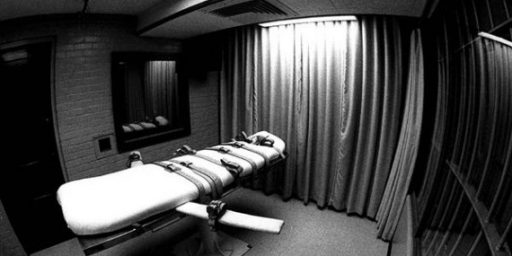

And yet, I still run into people who wonder why I oppose the death penalty.

Everything about that sentence utterly disgusts me. How can innocence have a statute of limitations? How can any inmate – let alone one with a 51 IQ – be expected to do the state’s job for it? How appalling.

This is a huge surprise but on further examination I find that Mr. Hartfield is black. A black man in Texas being deprived of his rights? Why, I never. Unheard of.

@legion: You beat me to it. What gets me is the absolute moral bankruptcy behind it. A man who has been found guilty of nothing should remain in prison because he missed his appeal by date. Unfortunately, this is nothing new.

Having worked/volunteered in the federal death penalty appellate office in a neighboring state in the early 90s, I have a sinking feeling that there may be a “jurisdictional” problem at the heart of this. At that time, the federal government had appellate death penalty resource centers across the country assigned to states with death penalties. Their objective was to appeal state or federal death sentences to make sure nobody was wrongly on death row and make sure that the appellate and petitions for writs of habeas corpus were handled efficiently by specialist in death penalty issues. Usually the defense trial attorney was not a participant (most likely since his/her handling of the trial would be attacked as a matter of course).

The appellate defenders had no authority over non-death cases; it was simply beyond the federal authorization. Add to that, Texas at the time was speeding its death row cases through the system and I was told many of the appellate defenders in Texas were becoming demoralized. Neighboring offices pitched in when they could. Its hard not to imagine this slipping through the cracks where the appellate defenders did their job by getting someone off death row, but there was nobody following-up on the potential implications of the ruling.

I don’t know how this is handled today, the federal death penalty resource centers were discontinued in the late 90s.

I don’t think his I.Q. would have made a difference at that time. I don’t think the courts cared, or the juries. In 2002, the SCOTUS banned the execution of the mentally handicapped.

@legion: He’s lucky he wasn’t executed anyway. Texas doesn’t seem to care anything about justice for anyone who isn’t white

Nothing about the Texas criminal “justice” system surprises me any more. :-/

@merl: They don’t care that much then, either. Ask Cameron Todd Willingham.

@PD Shaw: thanx for the insight PD.

A friend of mine was a Federal Public Defender in East St. Louis back in the early to mid nineties, and her case load was such that she burned out on the law in less than a decade. The ‘3 strikes’ laws were particularly demoralizing to her. She once had a client who got busted for the 3rd time on a “Distibuting a Controlled Substance” charge. What did he do? He shared a joint with a prostitute.

True story.

But, as we learned today, racism is OVER in Texas (and every other Section 5 jurisdiction), so I can’t see what y’all are so worried about.

I wonder how the victim’s family feels about all of this. A person was murdered by someone. The district attorney should review all of the evidence and see if it leads to someone else. There might even be some DNA evidence available now. If they still are convinced Hatfield did it then they could decide if 33 years is enough. His family may have some views about it.

It’s Texas! The state where most of the idiots seem to reside! No need to say anymore!!

John Fund applauds Texas’ innovation concerning limiting voter fraud.

@merl: “Texas doesn’t seem to care anything about justice for anyone who isn’t white ”

Or rich; I imagine that poor/working class white folk get the Longhorn as well.

When are the rest of us going to do something about the boil on our national behind that is Texas? Enough is enough.

Justice in Texas. You can’t compare it to the rest of the United States, apples and oranges.

Texas, however, is no worse than Iran or North Korea. Credit where credit is due.

@OzarkHillbilly: Especially in Texas, where the Gestapo is alive and well.

@OzarkHillbilly:

Hopefully she put out, or she’ll be arrested too.

@Tony W: No, just shot dead.

The nation’s legal system continues to evolve despite setbacks. In Massachusetts, a book dealer back in 1840 was arrested without a charge for selling the racy European novel, FANNY HILL, because a local policeman thought that what he did should be illegal. It wasn’t until a full year later, that the legislators of Massachusetts actually wrote a law to justify that arrest. In California, some San Francisco area medical marijuana businesses were prosecuted by the federal government, although San Francisco had local laws allowing those type of businesses. Judges used federal legislation passed by congress that limited the right of the defense to present evidence that these medical marijuana dealers were lawfully operating under local laws, where they were only represented to the juries as drug dealers, ensuring a 100% conviction rate. A California fetish adult filmmaker was put on trial three times for obscenity, after two mistrials, where persons involved in the movie industry in California were banned from the jury and evidence was misrepresented by the prosecution to ensure an eventual conviction. If government can’t win a case the first time, they can retry a defendant over and over again until they can’t afford good lawyers or expert testimony in their behalf and are eventually forced to plead guilty or will be convicted because they are ruined financially. Government has many ways to rig trials these days in order to convict a defendant.