The Stock Market And Elections: A Study In Correlation v. Causation

Can Wall Street predict the outcome of Presidential elections? Not really.

Brian Stoffel of The Motley Fool, who has a piece at Daily Finance (apparently an AOL site), seems to think he’s uncovered the key to predicting Presidential Elections:

This an election year, which means we are all faced with onslaught of political advertisements, prognostications, and endless poll numbers. Should candidates focus on values or the economy; foreign policy or domestic health care? Wading through all of it can be a difficult task for both candidates and voters.

But what if a look back at history showed that when it really comes down to brass tacks, there’s only one thing that determines the outcome of a presidential election?

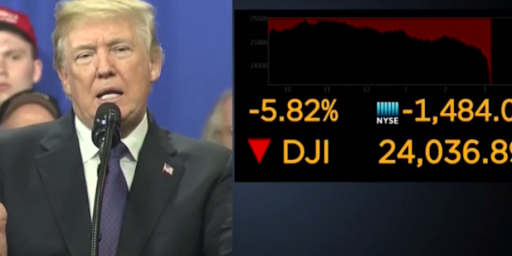

The single metric that has been astonishingly accurate at predicting the outcome of presidential elections has been the movement of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI) from Sept. 1 to Election Day.

In support of this hypothesis, Stoffell notes the case that in 25 of the 28 Presidential elections that have taken place since 1900, the incumbent party has won, or held on to, the White House. (Stoffel lays forth the results for the Dow and the election results in the article and I’ll just assume he’s got the numbers for the Dow correct) That’s a pretty amazing accuracy rate of 89.3%, a rate that would make any pundit green with envy and one that a gambler would die for.

But what are we really looking at here? Even Stoffel admits that it’s unclear that what he’s pointing out is a predictor of election results, or merely a coincidence:

It’s entirely possible that the market — anticipating a change in power based on publicly available polling numbers — discounts equities on the market to reflect the uncertainty associated with the coming change.

A strong case could also be made for the role of independent swing voters and what’s called the “recency effect.” This describes the common phenomenon in which people ascribe a disproportionate weight to the newest information we’ve received: In essence, whatever has just happened plays a larger role in our decision making than what occurred further in the past.

Casual observers can see the recency effect in action every college football season, as the national rankings — which are determined by human votes — tend to favor teams that had their only loss early in the season as opposed to in the final games of the year. In much the same way, it could be argued, voters are willing to ignore the previous three years and 10 months of a president’s administration, and instead focus on his final two months.

It’s certainly the case that traders in Wall Street will be looking at the election and the polls as we get closer to Election Day. However, I’m not sure that it’s at all accurate to say that the up or down movement of the Dow is based on their interpretation of the election outcome alone. Certainly, that’s going to be something that they take into account but they’re going to be paying far more attention to the general condition of the economy, both nationally and internationally, along with data such as a interest rates, bond yields, and corporate profits. Similarly. I don’t think that many voters, especially those “independent swing voters” that Stoffel talks about, are going to be paying attention to the daily ups and downs of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. They’re going to be looking at their own economic situation, along with that of their neighbors, and possibly the “big” economic numbers that get attention in the media such as the Unemployment Rate.

To the extent that the movements in the Dow end up correlating so strongly with the results of Presidential elections it’s likely because the stock market reflects the overall health of the economy, not because it is some great predictor of political outcomes, or even that it has that much influence over how voters behave once they get to the voting booth. If the economy is doing well, the stock market will generally reflect that fact, and if the economy is doing well then the incumbent party is likely to do well on Election Day. If the economy isn’t doing well, then the stock market will reflect that, and the incumbent party will have a much rougher day on Election Day. What we’ve got here, then, is a correlation, but one that merely reflects the fact that both the stock market and the electoral hopes of an incumbent both tend to be tied to the economy. It’s not a predictor, and it’s unlikely that the stock market alone plays that big of a role in the outcome of an election.

One final thought occurs to me. I have to wonder why Stoffel chose to limit this study to the correlation between the DJIA and the election. Yes, the Dow is the best known of the stock market averages, but it is hardly the one that is most reflective of the market as a whole. It’s an index that includes only 30 stocks, as opposed to the 500 included in the S&P 500, or the 5,000 included in the Wilshire 5000. Why limit this study to only the narrowest index and not one of the broader ones? Is it possible that the predictive value of the other indexes isn’t nearly as good as the Blue Chips? It would be interesting to find out.

The Dow and the S&P largely move in lockstep. I’ve little doubt if you overlaid the Standard and Poors it would produce the same outcome. The probable reason for the correlation of course as you say is because the markets are leading economic indicators. As to their effect on outcomes there’s little doubt in my mind that a rising stock market is going to be beneficial to an incumbent both directly and indirectly because of it’s impact on net worth calculations. The prevalence of 401k retirement plans have created far greater awareness of and interest in markets. A plus in your 401k or IRA statement is going to produce both a greater sense of general wellbeing and a greater propensity to spend. How beneficial is hard to say but it’s definitely a positive.

@Brummagem Joe:

Who actually believes that markets are leading indicators?

Old school investors and economists would believe the efficient market hypothesis, and the random walk, and say that there is no “leading.”

More modern chaos-friendly thinkers (Shiller, Taleb, Mandelbrot) would be more like “if not efficient, then noisy and unpredictable.”

(I concur Doug that a correlation like this is very suspect, both for reasons of indistinct causation, and selectivity.)

Mish:

@john personna:

Quite a lot of people actually. The fact that they can be chaotic is irrelevant to their status as indicators.

@Brummagem Joe:

Even if one concedes your point, that says nothing about whether the DJIA is a leading or lagging indicator.

@Rick Almeida:

Actually I said markets not specifically the Dow. One of the ten components of the Conference Board Leading Economic Index is the S&P 500. Take it up with them.

@Brummagem Joe:

Mish shows that, though the Conference Board “uses” it (who knows to what degree, really), it doesn’t actually work.

You know what would be great? Rather than some pointer that everyone just thinks it leads, a data study that shows it does.

@Rick Almeida:

Most people move to the averages being “coincident” indicators for equity appeal … which finds a sort of truth in tautology.

It’s entirely possible that the market — anticipating a change in power based on publicly available polling numbers — discounts equities on the market to reflect the uncertainty associated with the coming change.

This would make the market a lagging indicator, not a cause of the outcome. Such a phenomenon, if accurately observed, could contribute to a sort of feedback loop, but that’s not what Stoffel is saying.

Casual observers can see the recency effect in action every college football season, as the national rankings — which are determined by human votes — tend to favor teams that had their only loss early in the season as opposed to in the final games of the year.

Is that an example of the recency effect? I don’t know if there are any solid studies on this, but it seems unlikely to me. There are a host of reasons why people would be likely to rank a team that lost a game early higher than one that lost a game late in the season. An early loss can be seen as an indicator of a problem the team has overcome by late season. A late loss could be as a result of player injuries, which can obviously lessen a team’s strength going into the playoffs.

Like so many people looking for simple, easy to understand causes of complex social phenomena, Stoffel seems to make a number of specious assumptions. I blame those Freakonomics dipsits.

@john personna:

So what? He’s one blogger. It’s one of the ten components of their index of leading indicators and therefore, contrary to your claim, a lot of people take notice of it.

The bravo sierra detector is on full alert with respect to this puff piece by whomever this Stoffel character is. To say that September-November action in the DJIA is a direct predictor of presidential elections is like saying the weather in Oklahoma in July is a direct predictor of how cold it will be in Michigan in December.

The Dow and the other major indices normally drop from August through the end of September and then normally rise in October and November. That’s the “seasonality” factor of the stock markets. This normally occurs whether it’s a presidential year, a non-presidential year, a bad year, a good year, or an indifferent year.

Stock markets tend to be discounting mechanisms 6-9 months out. In other words what happens in the stock markets today tends to be reflective of what the markets think will be happening 6 to 9 months out in the future. Everyone who plays the markets knows this. Anyone affiliated with the Motley Fool would know this. Ergo if you wanted to try to make a correlation between the equities markets and presidential elections you’d need to look at historical data of what the markets were doing in the 1st quarter of presidential election years, not in the third and fourth quarters.

To say that incumbents have won the overwhelming majority of presidential elections is like saying the overwhelming majority of pregnancies lead to child birth. Um, yeah.

Incumbents always win the overwhelming majority of elections in which they participate, whether at the presidential level, the gubernatorial level, the congressional level, or anywhere else. The only occasions since the turn of the 1900’s on which incumbent presidents have lost reelection bids is when the economy and specifically the job markets were poor in the years leading up to Election Days.

Speaking of which, there is a reliable indicator of presidential election results when incumbent presidents seek reelection. Measure the unemployment rate in January of the year in which they seek reelection. Measure the unemployment rate as of November of that year. If the unemployment rate is the same or lower it’s overwhelmingly likely the incumbent president will be reelected. If the unemployment rate is higher, however, then the opposite is the case.

With Obama, however, none of the “conventional wisdoms” or predictors might apply. If you’re voting to reelect Obama you’re doing so strictly because of his skin color, because wealth or old age has corrupted your mind, because extreme youth and inexperience makes you incapable of making an informed decision, or because of tribal affiliation to a party label, not because of anything else. When they say that Obama is a “transformative” president they’re not kidding.

@Brummagem Joe:

That was a total fail, Joe. And it was typical of the way you get stupid and stubborn.

Mish presented data, and you dismissed it as opinion.

@Tsar Nicholas II:

This is as ridiculous as my saying, ‘If you’re voting against reelecting Obama you’re doing so strictly because of his skin color.’ Surely you wouldn’t agree with that statement.

Why beclown yourself so?

@john personna:

.

And name calling is typical of the way you respond whenever anyone demolishes one of your ridiculous generalisations. The fact is the S&P institutionally, and indeed unofficially markets generally however imperfect they may be, are widely regarded as leading indicators whether you choose to believe it or not.

@Brummagem Joe:

Data, Joe. That’s all it takes.

That’s what I asked you for in the beginning.

Actually it is really interesting that in this numbers driven domain you (and so many) go with “widely regarded” instead.

It is a prime example of irrationality. Of course I’m going to call that “stupid and stubborn.” I asked you directly for data, and you dodged.

@Brummagem Joe:

The above is called “appeal to authority.” Just because the cool kids are doing it doesn’t mean it’s accurate. A good rule of thumb is that equity markets are stupid because investors rarely understand the dynamics involved and most trades are performed via high-frequency trading anyway. That equity markets spiked as the recession continued to worsen should be an indicator that markets in aggregate do not recognize fallacy of composition.

@john personna:

Sigh….I didn’t dodge anything. You made one of your not uncommon ridiculous over generalisations which I demonstrated was incorrect. End of story. And I’m not particularly interested in either your name calling or boring efforts to talk your way out it.

@Ben Wolf:

Actually it’s a statement of fact and not a fallacy. Which is not to say that sometimes markets cannot be fallacious. And note I said markets not equity markets although they are certainly part of the picture.

@Brummagem Joe: Of course it’s a fact. It’s also an appeal to authority. The two are not mutually exclusive, one requires the other.

@Ben Wolf:

Of course it is, but above you suggested I was making a fallacious appeal to authority…viz

And btw this statement is another eyeroller…..

About 64% of trading on the NY and London stock exchanges is proprietary and therefore likely electronic. So right off the bat two thirds of market participants understand exactly the dynamics at work and the notion that the vast majority of the other third don’t either understand market dynamics or know that about the extent of electronic trading is absurd. This is not to say herd mentalities and all the other features of market trading are absent, but to suggest “investors” don’t understand the dynamics of the market is…er….to put politely….somewhat wide of the mark

Well (checking back after a nice walk across town), if anyone has data to demonstrate the “fact” that markets are a reliable leading indicator of the future economy, I’d be happy to demonstrate my mental flexibility and adapt.

BTW, never forget the old joke … that markets predicted the last 10 of the last 3 recessions.

Also I’d worry about the tautology aspect of this. The market is an important part of the economy. If the market crashes, a significant portion of the economy just crashed, and it will show up in slower ticking statistics. We get the SP500 in real time, a quarter’s GDP shows up with a lag.

A real-time GDP probably would not “lag” in everyone’s consciousness as much as the delayed one.