Ticket Splitting in the 2022 Mid-Term

How much ticket-splitting was there in gubernatorial v. senatorial races this cycle?

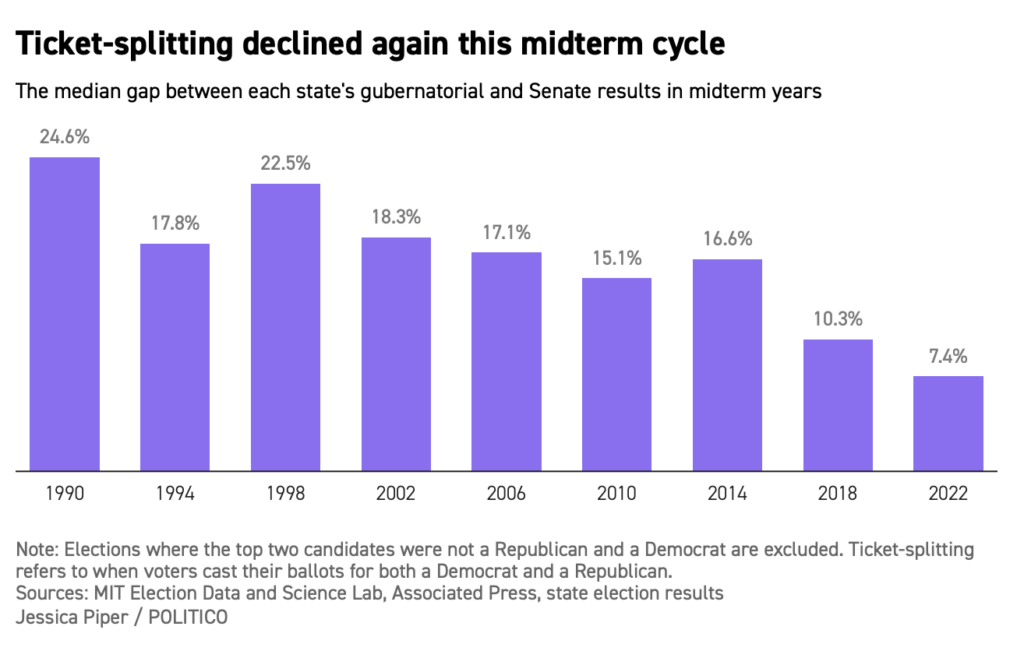

Politico has a piece whose headline is narrative-friendly but buries the lede: Voters who backed GOP governors helped keep the Senate blue. The headline emphasizes a narrative from the mid-terms that a lot of voters split their tickets between gubernatorial candidates and senatorial ones, such as in Georgia where clearly some voters voted for Republican Governor Kemp and then either abstained in the contest of Walker v. Warnock, or actually voted for the Democrat. However, the piece notes that really, ticket-splitting has declined.

Indeed, as the piece notes:

Democrats have ticket-splitters to thank for maintaining their hold on the Senate.

New Hampshire Democratic Sen. Maggie Hassan trampled her Republican rival, even as the state’s Republican governor, Chris Sununu, did the same to his opponent.

In Nevada, voters helped Democrats seal the Senate majority by reelecting Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto even as they tossed out the sitting Democratic governor.

So, all cool for the narrative that focuses (understandably) on some key races. However, the real story as it pertains to national partisan trends is the opposite and reinforces our understanding that the nation is pretty polarized and that existing partisan preferences are the key variable to understanding outcomes:

The results are enough to make it look like this year’s midterms represented a return to the old days of de-polarized statewide politics, when large numbers of voters would support one party’s candidate for Senate and the other party for governor.

But it was actually the opposite. A POLITICO analysis of the results shows that ticket-splitting in those races declined to the lowest point of any midterm since at least 1990.

So, while it is clear that some states did see important splits in partisan voting between governor and US Senate contest, the reality is that the overall trend is clearly to more unified partisan voting.

Two observations.

First, clearly, we are seeing that candidate quality matters, although even that fact is influenced by the partisan context (as we are seeing in Georgia wherein Walker is objectively one of the worst candidates for Senate one could conceive of, and yet has a shot at winning).

Second, I would note that governor is an office that appears to have a bit more influence of localized politics than several others which are more nationalized (which helps explain some of the ticket-splitting in general). For example, in 2019 a Democrat won the Kentucky gubernatorial race (by a very slim margin–49.% to 48.8%) even as the state went heavily for Trump (62.1% to 36.2%). I have thoughts on why this is the case, but will simply leave this as an observation for now.

At a minimum, these results do suggest that the general trend towards polarized, calcified electorates with nationalized parties continues, even if there are some notable exceptions.

The KY gubernatorial race was in 2019. While it’s likely Andy Beshear did win many votes from people who backed Trump in 2016 and 2020, it still wasn’t the same set of voters who showed up in the presidential elections, and it likely skewed Democrat. I don’t think Beshear would have won the gubernatorial election if it had taken place concurrently with the presidential.

Of course, this only supports your overall point about the decline of ticket-splitting.

Thank you for reading that. I saw the headline, said to myself, “Huh, I thought ticket splitting was down?” but never got back to read it. Now I don’t have to.

@Kylopod: Thanks for noting that. You are correct: if the gubernatorial race had been in a presidential year, I highly doubt a D could have won.

The basic point about governors is that even states that are otherwise strongly partisan in one way will sometimes flip for a governor (more, I think, than in other statewide circumstances).

@Steven L. Taylor: It still remains the case that most of the examples of governors from opposite-party states—Beshear, Laura Kelly, Phil Scott, Larry Hogan—weren’t elected in presidential years. That needs to be taken into account.

If I’m not mistaken, the biggest counterexample is Chris Sununu in 2020–he won by a 32-point margin in a state Biden carried by 7 points. Other recent examples, such as Roy Cooper in 2016 and 2020, are more modest—a state going narrowly for one party in the presidential and for the other for governor.

And I think Jim Justice in 2016 (basically a Republican running as a Dem in WV, almost immediately switched parties after the election) can be entirely discounted.

I do agree that governor’s races defy partisanship more often than federal ones. But even that’s getting increasingly minimized over time.

@Kylopod: Agreed all around.