TORT REFORM

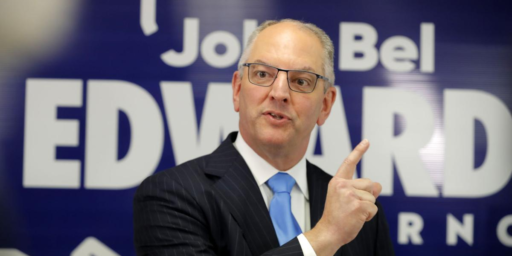

John Edwards has an op-ed in today’s WaPo on President Bush’s plan to limit medical malpractice lawsuits. Not surprisingly, Edwards, a malpractice attorney before entering politics, thinks the current system is basically fine and that the main problem is the insurance industry and bad doctors rather than frivilous lawsuits.

He does propose some logical-sounding reforms, however:

The most critical step is reforming the insurance industry. Today insurance companies use slow and burdensome processes to discourage both doctors and patients from filing legitimate claims. Worse still, these companies can fix prices and divvy up the country in order to drive up their profits. Even when companies don’t explicitly collude, they set their rates based on a trade-group loss calculation that they know other companies will follow. In any other industry, this kind of conduct would be subject to scrutiny under the antitrust laws. But an obscure 1945 law gives insurance companies a broad antitrust exemption. Because of the insurance lobby’s influence, Congress has even blocked the Federal Trade Commission from investigating insurance company rip-offs. These special privileges must go.

Next, we need to prevent and punish frivolous lawsuits. Most lawyers are responsible advocates for their clients, but the few who aren’t hurt the real victims, undercutting the credibility of the legal system and clogging our courts. For all his talk about frivolous lawsuits, President Bush does nothing to address them. He’s got it backward — instead of cracking down on irresponsible behavior and baseless cases, he’s targeting serious victims who win in court and are believed by juries.

Before a lawyer can bring a medical malpractice case to court, we should require that he or she swear that an expert doctor is ready to testify that real malpractice has occurred. Lawyers who file frivolous cases should face tough, mandatory sanctions. Lawyers who file three frivolous cases should be forbidden to bring another suit for the next 10 years — in other words, three strikes and you’re out.

Finally, we can reduce malpractice premiums by helping to reduce malpractice. The Institute of Medicine found that at least 44,000 people die from preventable medical errors every year. In medicine, as in law, a few people cause the most problems: Only 5 percent of doctors have paid malpractice claims more than once since 1990. This same 5 percent are responsible for more than half of all claims paid. One part of the problem is state medical boards whose discipline is as lax as state bar associations’. We need to provide resources and incentives for boards to adopt real standards on the “three strikes” model.

Why not do those things and enact basic tort reform? There’s no reason for them to be mutually exclusive.

While I appreciate the suggestion that a crackdown on frivolous suits is needed, Edwards needs to rethink his suggestions. For example, requiring an attorney to swear that he has an expert at the ready before filing suit is not feasible. In order to obtain the information necessary for an expert to determine whether malpractice has occurred, first one has to file suit. Only then can the parties engage in discovery. Even if such information were available without using the discovery techniques provided by the rules of civil procedure, Edwards has overlooked the effect of the statute of limitations on his suggestion. If an injured person has to wait to file suit until an attorney has enough information to be able to swear that he has an expert to attest to malpractice there is a substantial risk that his claim will be time-barred, especially since many states have a one-year statute of limitations for personal injury.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, how does one define frivolous to begin with…and by the way, Rule 11 and other inherent powers of the court to sanction are already in place to deal with frivolous claims.

The charge of collusion is easily made and rarely proven. Besides, the mathematics of probability (upon which actuarial science is utterly dependant) are invariant across regions of the country (or the world, for that matter). Thus, one would logically expect strong similarities in premiums–unless, say, the investment choices of the firms resulted in vastly different rates of return.

Also, both the legal and medical professions are suffering credibility problems–neither does an adequate job of policing incompetence and malfeasance within its ranks. Attorneys who bring frivolous cases should be immediately and strongly sanctioned–disbarment is not too strong a penalty for multiple offenses. Incompetent doctors should be decertified. And both the American Bar Associations and the American Medical Association should support registries to prevent those deserving of sanction from simply hanging out their shingle in a new location in order to defeat the process.

Finally, while the number of outrageous verdicts is relatively small, their presence forces the insurance industry to hedge its bets to guard against successful “lottery playing” by plaintiffs and lawyers. The lawyer’s self-serving argument that “you can’t put a value on human life”, is exactly right–actual damages (costs and loss of income for some reasonable period–not a 100-year lifetime of astronomical earnings, but 10 years of the average family income) and punitive damages up to twice that amount paid into a fund to support worthy causes (including care for the victims) are sufficient. The lawyer should get a share as well, but never more than a quarter of what the average victim gets–the era where a Peter Angelos makes several million dollars for a couple dozen hours work, a la the tobacco settlement, should be over.

—