US Intelligence Fomenting Overseas Protests?

A 34-year CIA officer's thoughts.

Retired CIA officer and current Georgetown professor Douglas London takes to Foreign Policy to ask a question that honestly never occurred to me: “U.S. Rivals Are Facing Unrest. Is It Due to Luck or Skill?“

In recent weeks, there have been major street protests in China and Iran, two of the United States’ main adversaries, and a mass exodus of fighting-age men amid an economic and military meltdown in Russia. Is it luck? Coincidence? Is CIA Director William Burns a total genius? Or is it the result of painstaking preparations to bring about a moment like this to bolster U.S. policy preferences?

Honestly, until I scrolled down to see his credentials, this struck me as sheer quackery. The notion that the United States intelligence community is orchestrating chaos of this level in three adversarial countries at the same time is fantastical. And, frankly, the causes of all three are long coming and, shall we say, overdetermined.

London continues:

The answer is complicated—as are the options for U.S. officials when it comes to exploiting the circumstances.

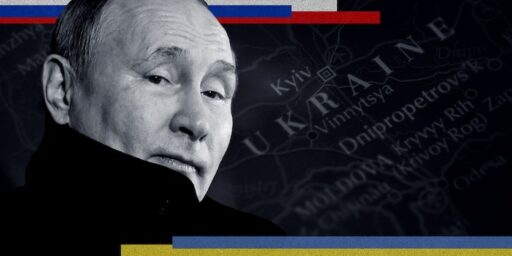

Russian President Vladimir Putin has for years routinely blamed the West for inciting protests inside Russia, just as he attributes the Ukrainian war to U.S. and European meddling. China’s government blamed “forces with ulterior motives” for the ongoing protests against the ruling Communist Party sparked by anger over the country’s costly zero-COVID policy. As crowds grew across the country, their chants included demands for greater democracy and freedom, with some even calling for the removal of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei have blamed the U.S. and Israeli governments for the ongoing protests that began after Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman from northwest Iran, died in police custody. She had been arrested by Iran’s morality police in Tehran for allegedly violating the country’s strict rules requiring women to wear a hijab, or headscarf. Iran has also blamed dissident Kurdish groups for instigating the unrest, responding with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and by launching missile and drone attacks against Kurdish enclaves. The United States, of course, has relationships with Kurdish groups across the region.

Blaming outside agitators is a longstanding go-to of leaders facing civil unrest. It’s a time-honored means of shifting the blame and delegitimizing the underlying grievances.

In Russia, protests against Putin’s war have been limited but might not fully reflect the underlying fissures and ongoing underground opposition, according to research recently highlighted by the Washington Post. Even as thousands of military-aged Russian men flee the country to avoid conscription, sabotage within Russia appears to be ongoing—and not necessarily by Ukrainians alone. Even hard-liners who support Putin and his war are becoming increasingly critical. Putin cronies such as Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder of the Wagner Group private military company, and Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov have been less than subtle in their attacks against Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Russia’s senior military commanders.

I have no inside knowledge of what the CIA and other US intelligence agencies are doing with regard to Russia. We’re certainly taking advantage of Putin’s Ukraine blunder by feeding the Ukrainian leadership intelligence and upgrading their armaments. But I’m skeptical, indeed, that we’re behind sabotage campaigns or somehow influencing Russian oligarchs.

Some U.S. adversaries even appear to be making rare concessions to domestic opponents. In China, just as Xi appeared to take a proverbial victory lap on securing his third term in power—seemingly bringing Hong Kong under the whip, setting his sights on securing reunification with Taiwan, and challenging the U.S. as the preeminent global military and economic power—internal unrest broke out over COVID restrictions, among other grievances, and it is a disruption to which he must respond—possibly by making concessions.

Sun Chunlan, Xi’s vice premier, recently told national health officials that the country is entering a “new stage and mission,” as several regions, including Shanghai, begin to lift lockdowns despite continuing high case numbers. Sun predicated changes on “the decreasing pathogenicity of the Omicron variant, the increasing vaccination rate and the accumulating experience of outbreak control and prevention.”

This seems like a reasonable political reaction to mass protests over COVID policy. Better to give a little that crack down.

Likewise, in Iran, the regime seems to be exercising restraint, at least to some extent. There is now uncertainty over the status of the morality police, which enforces its dress code, after Attorney General Mohammad Jafar Montazeri said they “have been shut down from where they were set up.” Although the New York Times was among those reporting the unconfirmed move as a possible concession to the protesters, local Iranian media outlets were quick to note that Montazeri’s remarks had been “misinterpreted.” Still, senior Iranian officials don’t generally go off script on their own, and the comments might have been a trial balloon.

The regime has detained thousands and killed hundreds, including dozens of children, in response to the protests. That they’re also suggesting they might loosen some policies is not all that impressive.

Despite the excitement, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines remarked while responding to journalists recently that “we’re not seeing the [Iranian] regime perceive this as an imminent threat to their stability and effect,” but “on the other hand … they are really having challenges and even nationwide seeing sporadic close-downs of businesses, [which] from our perspective, that’s one of those things that will lead to a greater risk of unrest and instability over time.” Iran “could face more unrest because of high inflation and economic uncertainty.”

Because Iran was a relatively modern, Western-leaning country under the Shah, we’ve had a four-decade fantasy of “Iranian moderates” getting their fear of the mullahs and seizing back power. I would love to see it happen, as I’m sure would Haines. That’s a far different thing than us orchestrating the protests ourselves, which would not only be very hard to do but would be likely to backfire. Help them along a little once they got going? I’d hope so. Start them? I doubt it.

Indeed, London agrees on that front:

Weakening adversaries from within is a page from Putin’s hybrid warfare playbook, but the unrest being manifested among major U.S. adversaries poses as much risk as it does opportunity. While I suspect U.S. intelligence operations are enjoying a period of major success, as reflected most publicly by its declassified reporting concerning Putin’s intentions in Ukraine and China’s response to the conflict, conspiracy theorists suggesting a direct U.S. hand in Iran’s and China’s current unrest would be disappointed.

It’s not beyond the United States’ means to sow unrest but doing so without any measure of control over the outcome is generally not a winning approach. Instability leads to unpredictability and escalatory possibilities in which desperate despots could look abroad for high-risk solutions. The internal consequences could also be worse for U.S. interests than what preceded them. If Iran’s government or Russia’s were overthrown, there is no guarantee that the successor would be more democratic or less violent; they could be even more brutal.

Promoting regime change is also a messy business. There’s a complicated political, economic, and military risk calculus to such enterprises, the mechanics of which are governed by exhaustive U.S. covert action legal authorities and requirements. Although U.S. regime change efforts over the years in Iran, Cuba, Chile, Afghanistan, and Iraq were not exactly well thought out and were based on a mistaken premise, at least there was a plan.

Fomenting civil unrest, whether it’s in the interest of regime change or simply to increase an adversary’s burden, can and does lead to an array of second- and third-order circumstances, some predictable, others not. At a minimum, the lawyers, of which there are many in the U.S. intelligence community, will tell you that there’s an expectation that facilitating such unrest will result in violence. The outcome will inevitably include deaths—requiring the written direction of the president with ensuing authorities and a memorandum of notification to congressional leadership and its intelligence oversight committees.

This is followed by several paragraphs on the history of such attempts and then this insight:

Over the course of my CIA career, it was not uncommon to be approached by political dissidents and even insurgent groups seeking a relationship with the U.S. government for support in changing their country’s regimes. Few were credible, and some of those who were offered a potentially greater risk to U.S. interests than the regimes they sought to replace. Even supporting legitimate, progressive, internal opposition movements can be a double-edged sword should exposure of cooperation damage those movements’ credibility.

Every good spy knows that in chaos, there is opportunity; as I wrote in the Wall Street Journal in March, “Spies Will Doom Putin.” And luck in exploiting such opportunities for an intelligence service is the product of a great deal of preparation and the long-term nurturing of relationships with the right people. The instability and unrest across the autocratic powers against which the United States competes creates an operationally fortuitous and target-rich environment.

The CIA is a strategic intelligence service, good at its work but not particularly adept at taking the pulse of the people or engaging with legitimate political opposition. It’s not supposed to. The CIA is good at engaging clandestinely with those who have access to secrets and power, and in this environment, I expect business in Russia, China, and Iran is good.

David Marlowe, the CIA’s deputy director of operations, called the invasion of Ukraine a massive failure for Putin and argued that could lead to opportunities for Western intelligence agencies recruiting disaffected Russians. Marlowe was speaking about those Russians pushed to the edge who are now more inclined to cooperate with foreign intelligence services. There is a large cross-section of Russians whose motivation in cooperating with the West might span patriotism, disgruntlement, and the pursuit of an insurance policy against harder times possibly to come.

But what if success in stirring opposition leads to constructive responses by the autocratic regimes the United States seeks to weaken? Could such meddling actually strengthen rivals who accommodate the demands of their citizens and thereby become stronger and more capable adversaries?

Again, it makes great sense to exploit the adversary’s mistakes for our own gain. And Russia, China, and Iran are all making plenty of them right now.

Alas, London isn’t all that hopeful as to how all of this will work out:

In China, could Xi’s easing of COVID-19 restrictions be the remedy to restoring China’s economy? Might Iran’s theologians gauge reaction to a possible temporary and superficial easing of social restrictions and leverage nationalistic themes? Will Putin manipulate the appearance of democratic concessions to create an illusion of popularity that becomes reality?

With the possible exception of China, it’s not likely. Iran has no room to maneuver. The current leadership requires its conservative religious credentials to legitimize the repression and brutality necessary to retain power. The Iranian regime’s actions in past uprisings reflect lessons learned from the 1979 revolution that partial compromises such as those with which the shah experimented before his downfall only encourage bolder opposition.

Putin similarly believes in the necessity of his image of invincibility, one that would be publicly undermined by any appearance of weakness that he perceives accommodation could cause. And even Xi can only go so far without raising protesters’ expectations and risk tolerance, but he has little need to lessen political restrictions. Xi’s most pressing challenge is to maintain the social contract of providing his 1.4 billion citizens a robust economy in exchange for their deference to China’s Communist Party concerning politics; restoring economic stability might require some opening up after harsh lockdowns.

That all strikes me as right. While it’s relatively easy for Xi to dial down his COVID Zero policy, Putin and the ayatollahs have little room for maneuver. For Putin, there’s no turning back from his disastrous war in Ukraine at this stage; too much blood and treasure have been lost. For Iran’s theocrats, there’s a myth to maintain.

London closes:

The conditions and circumstances from which Western intelligence services can profit are likely to build rather than recede in Russia, China, and Iran, given how undercurrents of resentment and resistance arguably grow in societies over time.

The United States should illuminate the wrongdoings and malign behavior of these despotic regimes and, with limited and carefully considered covert exceptions, overtly enable organic dissent, much as it did during the Cold War. That support must necessarily be deployed in a manner that doesn’t undermine courageous domestic efforts; it should be extended to groups that truly reflect their countries, and it mustn’t leave the U.S. government with even bigger problems than those it hoped to solve.

Again, I think he’s right. The Biden administration’s information operations against Putin with regard to Ukraine have been brilliantly effective: selectively linking intelligence to demonstrate Putin’s ineptness and magnifying Ukrainian wins to embarrass Putin. I’m more skeptical as to how successful we can be with China and Iran but shining on a light on regime excesses and helping protestors get their message out is all to the good.

There is a vast chasm of difference between initiating unrest and capitalizing on unrest that already exists. I have no doubt that the latter is what we are talking about here.

If anyone’s looking for an interesting twist on this, I recommend the podcast Wind of Change, which looks at the song by the Scorpions. Someone got it in their head that the CIA wrote the song, which was used as a sort of anthem as the former Soviet Union crumbled.

I find that suggestion a bit laughable, but I *do* think that it makes sense that the CIA might have been responsible for translating the song into Russian.

There is a small part of me that wishes that US intelligence was that good.

But an operation to formant descent, in insular countries like we are talking about, is fraught with unknowns. There are way too many vectors for such an operation to go sideways and blow up in our faces while getting a lot of people, who are willing to trust us, killed. It’s easy to convince ourselves that a group of dissidents is all in to fight for freedom, but you can never really tell what the actual level of commitment is on the ground.

Who was the Iraqi man that was telling the Bush administration that his people would welcome us as liberators? We sort of took that to mean all of them, not just a disaffected subset 🙂

Pre-Internet, my guess is that the biggest influence the US had on foreign populations was via the Voice of America shortwave broadcasts, and that was primarily because they told straight unbiased news about the world and also about the US, both good and bad. I used to listen back in my Peace Corps days and really appreciated it. News without a slant and no overdramatic lead ins or beating a subject to death because it generates outrage. Unfortunately the Republicans started ruining it during Bush 2’s term (don’t say anything bad about the US) and it’s likely Trump’s corrupt and partisan appointees have destroyed its credibility.

I would expect the bulk of CIA and other western TLA involvement will be on cultivating contacts and collecting intelligence.

After all, there’s a reasonable chance some of the key figures in some protest movements could be in national leadership ranks in the future.

Or alternatively, perhaps in a position to provide human source intelligence.

Or both.

Just highlighting that this is a time honored routine of local and state leaders here. Those riots that are in direct response to decades of leadership failures? Actually just coordinated rioters being bussed in from out of state. Nothing to see here, no real problems to solve, all the fault of others.

@Neil Hudelson: Absolutely. I chose the phrase “outside agitators” quite deliberately.

There’s no way to incite, foment, or even support unrest if there is no issue that large masses of people find unbearable, unfair, oppressive, etc.

One might supply the spark or fan the flames, but the pile of fuel and tinder were there already.

Oh, and those who play with fire tend to get burned.

Ahmed Chalabi, a man who hadn’t actually been inside Iraq in a long long time.

Regime change isn’t going to come from Chinese covid rioters or the brave Iranian women or Russian draft-dodgers. Some more potent force – the intel apparatus, the military, or a disciplined party – is needed. The truth is that repression works against popular demonstrations. Chaos offers an opportunity to those willing to risk exploiting it, but the question in each case, China, Iran and Russia, is whether there’s a force prepared to make a move against the regime.

Have seen several professionals remark on twit and blogs that CIA recruiting has probably had big boost, particularly given the details they knew as war began.

Given the standard tactic is to blame protests on outside influencers it may not be “all to the good” to get involved. Make no statements unless asked to do so, and then make them carefully if at all. The protesters, if they have a lick of sense, do not want to be labeled with anything other than their national identity and every effort will be made by the powers that be to label them otherwise. If we want change putting our stamp on it is unlikely to be helpful.

As John Lennon put it: “If you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao…”

I went to high school with a guy who I am 99% sure later became a spy. We were fairly good friends and stayed in contact. One summer he crashed with me for three weeks and slept on the sofa. I had to haul his sorry ass to the ER when he was going into anaphylatic shock from an allergic reaction to a bee sting. He was red as a beet and puffing up and struggling to breathe.

When he was senior year in college he signed up for Army OCS. Did his business and was commissioned as a freshly minted 2nd Lieutenant. The Army decided to send him to the Monterrey language school to learn Russian. At that point we fell out of regular contact.

Two years later I ran into his parents at a wedding and asked about [x]. His dad said he was in the Marine Corps now and was working at the US embassy in Moscow.

He was now a Lance Corporal in the USMC working embassy duty in Moscow, while a few years back he was a commissioned officer in the Army. This does not track at all. (Well, it tracks perfectly considering Monterrey.)

Dollars to doughnuts [x] was a spy. DIA, probably. Probably as a distraction or a magnet. His commissioning in the Army was public knowledge. Pay attention to this obvious guy and not his colleagues.