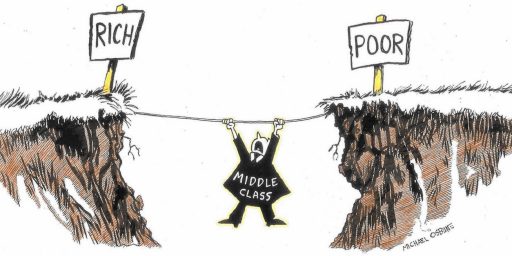

Where Did the Middle Class Go?

Why into the upper class, at least that is what Stephen Rose is arguing.

What’s the matter with the middle class? Democrats like to pin their defeats on national security and culture issues alone, but the progressive economic message is also to blame. What progressives generally say about the economy is unrelentingly pessimistic — stagnant wages, rising costs, overwhelming burdens of debt. It’s a message that doesn’t resonate with the middle class — not only because it’s overly negative (by itself political poison), but because it’s simply flat out wrong.

Don’t believe me? Believe the numbers:

- $63,300. That’s the 2004 median household income of people in their prime working years, ages 25-59 (it’s $70,000 for married households and nearly $80,000 for two-earner households).

- $248,700. That’s the median net worth of pre-retirement Americans, ages 55-64.

- Zero. That’s the median credit card debt for all American households.

Drowning in debt? Squeezed to the gills? Living paycheck to paycheck? I don’t think so.

[snip]

It’s true that the middle class is shrinking — but that’s because more families are better off. The share of prime-age adults in households with real incomes above $100,000 rose by 13.1 percentage points from 1979 to 2004. The share of households making less than $75,000 dropped by 14 percent. Fully 41 percent of prime-age American adults are in households with incomes above $75,000.

[snip]

I focus on prime-age households (age 25-59), which are 68 percent of the population, because including the very young and the very old distorts the picture of what’s really happening with the middle class. Many young workers get paid very little, but few will keep their low salaries as they move up in their careers. Older Americans distort the wage and income picture because they’re no longer working. Their incomes may shrink, but their standard of living may not diminish. Indeed, Americans age 55-64 have greater net wealth than any other group.

Of course, the policy prescriptions he suggests are somewhat dubious.

Two things set the top quintile apart: people in the top quintile are much more likely to have finished college, and they are much more likely to be in married, two-earner families. We can move more people up the ladder by doing two things: one, by helping more students graduate from college, and two, by supporting two-earner families in balancing work and family. This means such things as broad-based tuition tax relief, paid family leave, and more tax breaks for child care costs.

There is a potential problem with causality here. While I don’t doubt it is true that having a college degree and being in a two-earner household are key characteristics of those who are in the top quintile, the idea that increasing the number of college graduates is the solution is dubious. Think of it this way, why not pass a law that simply grants all adults who don’t have a college degree a college degree. Would this change anything? No. Employers and future employees would find another means by which to seperate themselves. It might be advanced degrees or some other method. Or more simply put, highly motivated people are also likely to be successful. Highly motivated people are also likely to go to and finish college. So while being highly motivated and going to and finishing college are correlated, attaining the latter does not necessarily imply the former.

Via Greg Mankiw.

UPDATE (James Joyner): Not to mention the fact that the upper quintile is, by definition, limited to twenty percent of the population. Just as half of all doctors were below the median in their med school class, eighty percent of people will fall below the upper quintile.

Zero. That’s the median credit card debt for all American households.

Yeah, like the *median* is really a useful indicator of anything here?

And $63,000 a year for a family with kids isn’t going to get you very far.

I agree with Anderson about the credit card debt figure. I do not know anyone that has absolutely no credit card debt.

But, $63,000/year with 4 kids won’t go far in northeastern urban areas (New York and DC), but it is certainly provides for a comfortable lifestyle in other areas like the southern states.

Oops, maybe FOUR kids was stretching it. I was trying to say a family of four – 2 kids!

Actually, I find this amusing. Many on the Left have slammed Bush and company for using statistics that aren’t the median, noting that things like income (and debt) can have a skewed distribution making the median the better indicator. Yet here is Anderson telling us not to use that statistic. Pray tell Anderson what measure of debt should be used?

I don’t know where he is getting his numbers…I would guess the heritage foundation or some equally dubious rightwing think tank!

I have no credit card debt, Mark. Of course, you don’t know me… so it doesn’t make what you said false.

And I’m fairly confident that many Americans don’t have any credit cards at all, or do have some but don’t use them or pay the balance each month.

Steve, you are way smart enough to know that median figures are useful for some things & not others.

What measure of debt *should* we use? Depends on the question, I suppose–I’m not an economist, I just recognize obvious b.s. now & then. (What’s the average credit-card debt per household, broken out by income quintiles, for instance? That would be interesting.)

Mark,

I’m another of those ‘no credit card debt’. I pay off the bills every month. You could say I have a credit card debt in that I have charged things, not received a bill and so haven’t paid. But I think that paying it off every month qualifies as no credit card debt. I tend to use my credit cards in place of cash (like renting a movie for $0.99 would likely go on my card), so almost always have a charge pending. That’s okay. I get some nice bonus points on the charges. But it wouldn’t take long on the credit card companies interest rates to wipe that out.

I also don’t have any car debt. I pay cash for the car, save what would have been my car payments while I drive it and then when I need a new car, I can pay cash.

I was surprised that the median debt was 0. I know more people who pay off every month than don’t, but I think that is more a factor of the limited number of people I exchange that sort of information about this sort of thing.

My parents were the same way, as are two of my siblings. The third sibling has never quite figured this out and periodically gets in trouble on credit card debt.

Me too – 4 kids, single income family, self employed

Running up credit card debt isn’t an economic factor it’s a lifestyle choice.

What I meant to write is that I also have no credit card debt.

Anderson,

Of course, but why should we expect the distribution of debt to be symmetric? A person at the lower end of the distribution likely has less debt than a person at the higher end of the distribution. Or, think of it this way, is debt and income/wealth correlated? If the answer is yes, then if the income distribution is skewed then maybe the debt distribution is as well. In short, you need to tell us why you think that the distribution is symmetric about the mean (and median).

Further, if the distribution is skewed then the mean is “pulled” in the direction of the skewness. Hence if the conjecture that debt and income are correlated then it could very well be the case that using the average would give us a result that is larger than it really is.

Madmatt,

The guy who wrote the article is not affiliated with the Heritage Foundation, but instead the Third Way, “A Strategy Center for Progressives”. Do try to click the link in the future.

Well, credit card debt is an important factor, but there’s a heckova lot more to it than that.

That’s because he’s not thinking. Or at least, dodging the issue. He does at least acknowledge later on that

But that ignores other significant sources of debt, like car loans and student loans and this plays heavily into any rational policy discussion. The relative importance of the debts is critical for two reasons:

First, if you can’t make good credit card payments, your credit rating goes bust. Eventually you might have to declare bankruptcy, but it doesn’t really help anyone to go that route – banks & CC companies often try to work such things out into reasonable payment plans. Mortgages, OTOH, are a different thing – they’re physical assets that can be foreclosed & re-sold. Trouble making your mortgage payment (or car note, for the same reasons) is a much more stressful thing than late CC payments.

Second, despite the fact that he notes the higher earners being more likely to have completed college, I didn’t see any relating of degree to student loan debt. While it’s not as big as a mortgage, it can easily equal a car loan in size & time to pay off…

The median credit card debt CANNOT be zero, because nobody can have negative credit card debt. At best, you can have zero credit card debt. Therefore, if anybody at all is carrying a balance, then the median must be higher than zero.

Indeed, later on in the article, the author himself admits that the median credit card debt is $2100. I don’t know where he pulled that zero from.

Interesting essay. The problem with it is his reference to assets held in home value. With home values increasing at much lower levels – and possibly soon to be decreasing, and ARM mortgages ready to float, home equity loans are going to be more problematic over the next few years. Rosen assumes that we don’t face any serious downward housing prices and no impending ARM problem. That’s not a wise assumption.

On the other hand, I think he is correct about overall incomes. And I do think that making college affordable will help. Sure, businesses will always ratchet up the qualifier, but that’s not really the issue. The problem is that men without college education are actually falling in wealth. I see it here in Michigan. The union manufacturing jobs are gone. That doesn’t mean that if they all go to college it will somehow degrade the notion of a college education and thereby force companies to raise their standards. Rather, it means they’ll be able to compete in today’s global economy. Getting the rust belt folks out here in Jackson and Calhoun County, Michigan, or in Warren or Detroit to go to college would make their own prospects so much better. Public policy should be geared towards it.

Alex, you may want to go back and read the article:

And after that a review of basic statistics might be useful, by the fact the 54% (100 – 46 = 54) of Americans do not in fact have and debt the median value can therefore be zero. To back me up I go to the basic definition of the median value:

And for an example of this in practice, try here. Illustrated as simple 5 number series it would look like this (with the median value in bold): 0, 0, 0, 2100, 10000.

Actually to show how the article’s example works it would look like the following (median in Bold):

Including Zero debt people: 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 2100, 10000

And eliminating people with Zero debt: 5, 2100, 10000

Pirate,

You’re right–that’s my mistake for not paying attention.

However, I will say this: I’d be interested to see how many people have “zero credit card debt” because (a) their credit is too bad to get a credit card or (b) they’ve declared bankruptcy.

If you take out those two groups a different picture may emerge. Or not. I don’t know. But I suspect that it would.

I think where you live has a whole lot to do with how far 60k can go. 60k in a lot of Southern States can buy you a nice home, and probably send your kids to a private religious school.

In New England where we live with our four kids it doesn’t go quite as far, but we still own our home.

I do think how much credit card debt is carried is a huge issue, and credit cards can easily allow a person to live above their means.

Which highlights the problem with the mean as well. The average debt in this example is $1,729.29. However 71% of our sample has no or negligible debt.

Ideally, all the statistics for a (sample) distribution should be presented so that we can get an idea of what it looks like.