Breaking: Jobs That Pay Nothing Don’t Always Pay Off

If you agree to work for nothing, don't complain you're being "exploited."

The New York Times informs us that recent college graduates are finding that unpaid internships aren’t leading to those bright careers that they hoped for:

The New York Times informs us that recent college graduates are finding that unpaid internships aren’t leading to those bright careers that they hoped for:

Confronting the worst job market in decades, many college graduates who expected to land paid jobs are turning to unpaid internships to try to get a foot in an employer’s door.

While unpaid postcollege internships have long existed in the film and nonprofit worlds, they have recently spread to fashion houses, book and magazine publishers, marketing companies, public relations firms, art galleries, talent agencies — even to some law firms.

Although many internships provide valuable experience, some unpaid interns complain that they do menial work and learn little, raising questions about whether these positions violate federal rules governing such programs.

Yet interns say they often have no good alternatives. As Friday’s jobs report showed, job growth is weak, and the unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds was 13.2 percent in April.

Melissa Reyes, who graduated from Marist College with a degree in fashion merchandising last May, applied for a dozen jobs to no avail. She was thrilled, however, to land an internship with the Diane von Furstenberg fashion house in Manhattan. “They talked about what an excellent, educational internship program this would be,” she said.

But Ms. Reyes soon soured on the experience. She often worked 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., five days a week. “They had me running out to buy them lunch,” she said. “They had me cleaning out the closets, emptying out the past season’s items.”

Ms. Reyes finally quit when her boss demanded that she also work both days of a weekend.

Well, of course they did. Stories of interns being given menial assignments and worked to death are as old as internships themselves. There are blogs and Twitter accounts that make fun the entire process of the summer interns that make their way into the offices of the District of Columbia every year, and while most of them are probably an exaggeration they point out a very simple truth — if people know that you’ll work for free, they’re very likely to give you a lot of crap work to do. Now, many will argue that there are advantages to the internship idea because it has the potential to lead to a paying job somewhere down the line, or at least that it’s something to put on one’s resume for future job interviews. I suppose there’s some value in that, although I’ve got to think that there’s far less value to it in an era where jobs are few and job applicants are plentiful than there was when the situation was reversed. If you’re going to go down that road, though, you probably need to go into it with both eyes open and realize that you’re not just the lowest guy on the totem pole, you’re not even on the totem pole.

There’s another side to this coin, of course, because many are arguing that the proliferation of unpaid internships, especially in private industry rather than government or entities that regularly deal with the government, amounts to unpaid labor in violation of existing laws:

The Labor Department says that if employers do not want to pay their interns, the internships must resemble vocational education, the interns must work under close supervision, their work cannot be used as a substitute for regular employees and their work cannot be of immediate benefit to the employer.

But in practice, there is little to stop employers from exploiting interns. The Labor Department rarely cracks down on offenders, saying that it has limited resources and that unpaid interns are loath to file complaints for fear of jeopardizing any future job search.

No one keeps statistics on the number of college graduates taking unpaid internships, but there is widespread agreement that the number has significantly increased, not least because the jobless rate for college graduates age 24 and under has risen to 9.4 percent, the highest level since the government began keeping records in 1985. (Employment experts estimate that undergraduates work in more than one million internships a year, with Intern Bridge, a research firm, finding almost half unpaid.)

Of course, if an unpaid intern doesn’t like the way the internship is going, there’s really nothing the “employer” can do to stop them from leaving. It’s not like the intern is going to suffer any financial losses if they stop showing up for a job that they’re not getting paid for to begin with so, other than the fear that walking away from a potential opportunity could harm their future career, the argument that they’re really being “forced” to do anything is rather absurd. They could just as easily spend the day watching reruns on cable if they didn’t think the internship was of any value to them any more.

It’s really a buyer beware situation. If you’re going into a position that you’re not getting paid for solely for the purpose of getting “experience” or “a foot in the door,” then you are going in with your eyes open. Complaining that you’re being exploited is really rather silly.

Unpaid interns don’t have to wait for the government to protect them, they can lawyer up and sue like the unpaid interns working in the Black Swan movie.

The problem comes when competing with those that do work the unpaid internships. It becomes “forced” by proxy. Not by the government’s standards (who ban this practice described anecdotally), but reality is reality, and reality says those who don’t bother with this are going to get dusted.

It’s painful logic – you must basically whore yourself out to get a kiss – but it’s what’s happening.

i.e. The BS industry

While some is exploitive, just being in the room is where the intern gains their experience. Clearing out last years items could be a learning opportunity as you see what sold and what didn’t. What an unpaid intern is very unlikely to do is contribute to the current work, both by inexperience and, as we see, government edict. The same occurs with student programs. They aren’t there long enough to become a contributing employee, they are around the productive people and can learn the ropes. They might be given a backwater assignment that offers an opportunity to discover something even if it is “menial” work.

Sorry but regardless of how brilliant your professors told you you were, you aren’t going to be value added much beyond taking some of the menial work off the productive workers as you get to “work” alongside them. And guess what, it’ll be the same for the first year of your paid employment only you probably won’t be asked to the meetings or sitting in on the discussions as a new hire. Work and school are for the most part not directly correlated.

Anyone else get the impression JKB hates people with an education?

So Doug, short of slavery, is there anything you don’t believe an employer should be allowed to do to an employee?

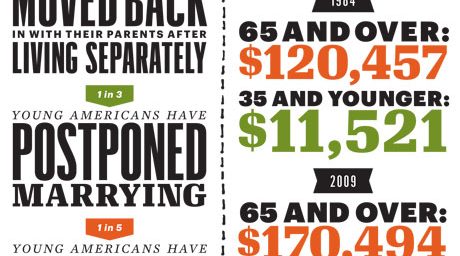

Since internships on the resume are often the only way to get interviews for the entry-level positions, this limits the entry-level positions to those that can afford to work for free for a while — kids with upper-middle class parents.

Which is a nice way of keeping out a lot of minorities.

Ah, freedom.

@WR: I’m sure that the classically libertarian employment position would be pro-indentured servitude. And likely pro-debtors’ prison.

And why on earth would unpaid interns be concerned with harming their future career?

“Melissa Reyes, who graduated from Marist College with a degree in fashion merchandising….”

Well, there’s your problem. Why not get a degree in something useful, rather than a fancy basket weaving degree…actually, basket weaving would surely be a craft in which one could make money.

Too many young people suffer from the dreaded Special Little Snowflake syndrome. They’ve all heard stories about how difficult or impossible it is to find jobs in certain fields or with certain types of degrees, but each one thinks “Well I’m a Special Little Snowflake, everyone else may suffer but I’ll do fine.”

Reality check: you’re not special.

The (racist) HBO series “Girls” dealt with the internship scam in the first episode. The main character, Hannah, had been working at an unpaid internship in the publishing industry for over a year, a workable arrangement because her parents were bankrolling her. When they cut her off, she asked her boss if she could be paid, and got herself fired.

I’ve written about the topic quite a few times over the years, as the news media keeps “discovering” it. In the DC nonprofit industry, doing a stint or three as an unpaid intern is virtually the only way to get in the door. There are just a plethora of people with fancy degrees and no experience out there applying for every low level job and doing internships is the only way to get some useful experience to put on the CV.

My problem with it isn’t that the interns often get assigned menial work or have to put in long hours; that’s just dues paying, so far as I’m concerned. The problem, however, is that it perpetuates the inequalities of the class system. By and large, it means that the sons and daughters of the rich and powerful–who already have a leg up by the network advantages and propensity to go to prestigious schools–get yet another advantage, in that they’re the only ones who can afford to work for months and even years in expensive towns like DC, New York, and Los Angeles for little or no money. There was simply no way that I could have moved to DC and done unpaid internships coming out of college.

@James Joyner:

Indeed, one wonders how it would even be possible without family money, savings, or a stipend

As odious as the internship scam may be, it pales in comparison to the life insurance scam. Almost all life insurance companies hire people for straight-commission agent “jobs” knowing that the vast majority of them will make no money and wash out of the industry. Failure rates are upward of 90% within a year. There is absolutely no selectivity in hiring, no matter how prestigious the company may seem it will hire just about all applicants. To make a bad situation even worse, many newly hired agents spend money they can’t afford on various schemes that are supposed to bring them business: mass mailings, participation in company publicity events, and subscriptions to paid lead services. All of these things cost money and all of them are nearly worthless.

@Doug Mataconis:

It really isn’t. As upper middle class parents, so far we’ve underwritten (i.e., paid through the nose) for a three month unpaid internship in New Orleans for the oldest kid and an eight week internship in New York City for the youngest .

The oldest also did a semester long internship during her senior year of college and, with no job prospects materializing after getting her Masters, jumped at the opportunity a second internship offered, if just to pump her resume up a little. It worked, and she was offered a job, at a decent salary, in less than a month after her internship ended. No, it wasn’t with the company she interned for, but their glowing letter of recommendation, along with her clips, helped her nail down the job she did get.

While we don’t yet know how much last summer’s internship for the younger one will pay off (he still has a year of college left), he did feel like he gained a lot of technical knowledge working as an unpaid PA for a large production company in New York. As part of his degree requirements, he’ll have to do another internship this year, while at school, but at least that one won’t cost us any out-of-pocket money.

If we could not have afforded to pay the living expenses for them to live out of town while doing these internships, there is no way either child could have done it on their own. So yes, these internships, which seem to almost be required in order to get a foot in the door for a job, do favor the children of upper income parents, which seems patently unfair to less well off students.

@Doug Mataconis: As the saying goes, “it’s not a glitch–it’s a feature.”

@Doug Mataconis: That’s what the really big problem is.

When you have to put in the odd year or two or three or four for free, on top of getting a degree from a ‘good’ (expensive) school, we’re pretty close to a world where you have to come from the right family to get into certain fields.