Common Cause Files Ridiculous Lawsuit Against The Filibuster

Common Cause has filed a specious lawsuit alleging that the filibuster is unconstitutional.

Common Cause, along with a group of Democratic Members of Congress, has filed a lawsuit in Federal Court in Washington, D.C. seeking to have the Senate filibuster declared unconstitutional:

For years, critics of the filibuster have failed to convince senators to change the procedural delaying tactic. Now they’re taking their case to the courts.

The nonpartisan nonprofit Common Cause sued the U.S. Senate on Monday, challenging the constitutionality of the filibuster rules that require routine 60-vote thresholds for bills and nominations that often have majority support. Several House Democrats and three undocumented students who would be aided by the so-called DREAM Act also joined the suit.

The lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, comes at a time of increased partisan gridlock in the Senate and amid complaints the filibuster is being abused by minority Republicans.

(…)

n addition to Common Cause, three DREAM Act students and four House Democrats — Reps. John Lewis and Hank Johnson, both of Georgia, Michael Michaud of Maine and Keith Ellison of Minnesota — were named as plaintiffs in the suit.

The students, who were born outside the U.S. and brought to the country illegally by their parents, claim they were denied a path to citizenship because of the archaic 1975 filibuster rule. During the 2010 lame-duck session, the DREAM Act, backed by President Barack Obama, won passage in the House and attracted a simple majority of 55 votes in the Senate, but fell short of the 60 needed to break a GOP filibuster.

The Democratic lawmakers argue that their votes in the House have been “diluted” by the filibuster rule, since such bills as the DREAM Act and campaign-finance DISCLOSE Act passed the House and won backing from a majority of senators but fell short of the 60-vote threshold. The DISCLOSE Act garnered 59 votes in the upper chamber.

“These bills continually pass the House and get blocked in the Senate,” said Sarah Dufendach, vice president of legislative affairs for Common Cause, which pushed for the DISCLOSE Act. “Their vote is being diluted. Their constituency is being diluted.”

Of course, one could make that “dilution” argument about any vote in the United States Senate considering the fact that several Senators represent states with smaller populations that some Congressional Districts, but that is how the Founders designed the Constitution. The Constitution also contains a provision that says that the House and the Senate are the sole arbiters of their own rules, so one could make a fairly good case that the filibuster rule is per se Constitutional notwithstanding the dilution argument or the alleged “unfairness” of the whole thing.

The attorney behind the lawsuit is a man named Emmet Bondurant who in 2011 published an article in the Harvard Journal Of Legislation [PDF] arguing that the filibuster is unconstitutional, which Ezra Klein summarizes:

In 1806, the Senate, on the advice of Aaron Burr, tried to clean up its rule book, which was thought to be needlessly complicated and redundant. One change it made was to delete something called “the previous question” motion. That was the motion senators used to end debate on whatever they were talking about and move to the next topic. Burr recommended axing it because it was hardly ever used. Senators were gentlemen. They knew when to stop talking.

That was the moment the Senate created the filibuster. But nobody knew it at the time. It would be three more decades before the first filibuster was mounted — which meant it was five decades after the ratification of the Constitution. “Far from being a matter of high principle, the filibuster appears to be nothing more than an unforeseen and unintended consequence of the elimination of the previous question motion from the rules of the Senate,” Bondurant writes.

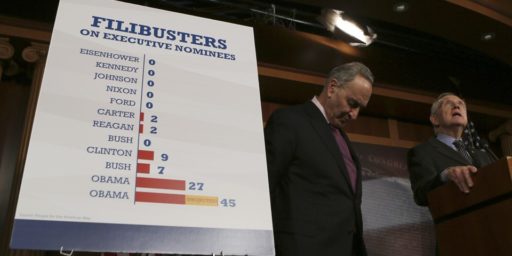

And even then, filibusters were a rare annoyance. Between 1840 and 1900, there were 16 filibusters. Between 2009 and 2010, there were more than 130. But that’s changed. Today, Majority Leader Harry Reid says that “60 votes are required for just about everything.”

At the core of Bondurant’s argument is a very simple claim: This isn’t what the Founders intended. The historical record is clear on that fact. The framers debated requiring a supermajority in Congress to pass anything. But they rejected that idea.

(…)

n the end, the Constitution prescribed six instances in which Congress would require more than a majority vote: impeaching the president, expelling members, overriding a presidential veto of a bill or order, ratifying treaties and amending the Constitution. And as Bondurant writes, “The Framers were aware of the established rule of construction, expressio unius est exclusio alterius, and that by adopting these six exceptions to the principle of majority rule, they were excluding other exceptions.” By contrast, in the Bill of Rights, the Founders were careful to state that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

That majority vote played into another principle, as well: the “finely wrought” compromise over proper representation. At the time of the country’s founding, seven of the 13 states, representing 27 percent of the population, could command a majority in the Senate. Today, with the filibuster, 21 of the 50 states, representing 11 percent of the population, can muster the 41 votes to stop a majority in the Senate. “The supermajority vote requirement,” Bondurant argues, thus “upsets the Great Compromise’s carefully crafted balance between the large states and the small states.”

Klein seems to think that this lawsuit has merit, and that it could pose a threat to the filibuster, but his Washington Post colleague Jonathan Bernstein disagrees rather strongly:

The plaintiffs argue that the Constitution specifies certain votes require Senate supermajorities, and therefore the supermajority for cloture conflicts with a constitutional presumption that all other votes will be by majority rule. That logic just doesn’t make sense.

The simplest way to reconcile the requirement of certain supermajorities with the instruction that the Senate gets to set its own rules is to say that the Senate sets its own rules except for where the Constitution specifies otherwise. Thus the Senate does not have the option of not keeping a journal of its proceedings, but it does have the option of whether to make all votes recorded votes; it must use a supermajority for passage of treaties but can choose to handle floor procedure however it sees fit.

Looking at the larger picture, the Common Cause group makes much of majority rule. The truth is that filibusters (and their much-despised cousin, holds) are only one way that the Senate, and that Congress in general, subverts simple-majority rule. The majority party can prevent popular items from coming to a vote by killing them in committee, by simply refusing to offer them on the floor or by blocking amendments from being offered.

It makes little sense to say that the Constitution requires a simple majority to bring something to a vote on the Senate floor but permits a well-positioned minority to block it before that point.

To put it another way, eliminating the filibuster wouldn’t achieve majority rule in the Senate; it would achieve what the House has — majority-party rule. That’s a very different thing. And it’s extremely difficult to believe that the Constitution mandated majority-party rule, given that parties didn’t even exist yet.

Jonathan Adler at The Volokh Conspiracy is on the same page as Bernstein:

I don’t think this suit will go anywhere. The first obstacle is standing. The failure of the Senate to pass a bill is not a legally cognizable injury, even if that bill appears to have majority support. The second obstacle is the political question doctrine. This obstacle is particularly large given that the Constitution expressly gives each house of Congress the power to set its own rules, so there is a textual commitment of this question to a coordinate branch. All of the cases upon which Bondurant relies to establish justiciability involved challenges to legislation or other acts that passed Congress and altered pre-existing rights and obligations, so they offer little support for Common Cause’s claims. Even were a court to get beyond these justiciability concerns, the suit would likely fail on the merits. If the Constitution authorizes the Senate to set its own rules, there’s no reason why the Senate cannot opt to include supermajority rules in its procedures.

The problems with this legal challenge are further magnified by Common Cause’s decision to challenge the use of the filibuster to block substantive legislation. The argument that the use of filibusters violates some unstated-albeit-enforceable constitutional norm is stronger with regard to items on the executive calendar (such as nominations) than it is with legislation. One could argue that the Senate’s obligation to “advise and consent” presumes an obligation to act — specifically, an obligation to hold an up-or-down vote — and that the filibuster prevents the Senate from fulfilling this duty. It is much harder to argue that the Senate must hold follow rules that allow for substantive votes on legislation. While it’s likely a challenge to nomination filibusters would also be found non-justiciable, it is more plausible than the claim Common Cause filed.

Adler has a good point in the second paragraph. There’s a difference between arguing that the filibuster has blocked Senate consideration of a specific piece of legislation and arguing that it has blocked the Senate from fulfilling one of its Constitutionally mandated functions such as the consideration of Presidential nominees and treaties, and conducting a trial after impeachment of an officer of the Executive or Judicial Branches of government. In the first case, as Bernstein notes, even if the filibuster there are any number of ways that a piece of legislation can be blocked from ever being considered on the merits. That’s not necessarily true in the second case, where the absence of a filibuster would require Senate action of some kind and an up-and-down vote. Had Common Cause used one of those Constitutional situations as the basis for their lawsuit, rather than the mere fact that the DREAM Act was blocked by a cloture vote, it might have a better case to make.

Even in that situation, though, their lawsuit faces serious problems simply because of the wide latitude that the Constitution gives to the House and the Senate to set their own rules. As Bernsteain and Adler both note, the Courts have generally demurred from getting involved in disputes involving the rules of either House of Congress because of this latitude, and have ruled that the cases that challenge them are barred by the “political question” doctrine. Since the Constitution is silent on what kind of vote the Senate must use to handle procedural matters on the floor, there’s no reason why the Senate cannot adopt a rule that requires a supermajority to proceed on a matter as part of an overall package of rules designed to balance the rights of the majority with the rights of the minority. Furthermore, there’s been some form of the filibuster in the Rules of the Senate since at least the 1830s. The idea that the Courts are going to step in now and say that the rule is unconstitutional is simply ridiculous, especially when there is clear historical evidence that the filibuster was not the “mistake” that Bondurant’s argument makes it out to be:

John Quincy Adams wrote in his memoir that the early Senate rejected a rules change that would have limited debate, because in 1806 Vice President Aaron Burr argued that a rules change was not necessary to end debate on a question. According to the late Senator Robert C. Byrd’s in The Senate, 1789-1989, “Henry Clay, in 1841, proposed the introduction of the ‘previous question’ but abandoned the idea in the face of opposition.” Byrd also noted that ”when Senator Stephen Douglas proposed permitting the use of the ‘previous question’ in 1850, the idea encountered substantial opposition and was dropped.” According to Byrd, “An effort to reinstitute the ‘previous question,’ on March 19, 1873, failed by a vote of 25-30.” Byrd cited the following: “Between 1884 and 1890, fifteen different resolutions were offered to amend the rules regarding limitations of debate, all of which failed of adoption.” This is evidence that the filibuster was not an accident of history, yet it was an accepted practice that was validated by Senate votes.

Finally, although this doesn’t necessarily go to the merits of the lawsuit, it’s worth pointing out that a mere seven years ago, Common Cause was defending the filibuster:

In 2005, Common Cause vigorously defended the filibuster when some Republicans proposed invoking the “nuclear option” to end the filibuster of judicial nominees. From a 2005 press release:

Common Cause strongly opposes any effort by Senate leaders to outlaw filibusters of judicial nominees to silence a vigorous debate about the qualifications of these nominees, short-circuiting the Senate’s historic role in the nomination approval process.

“The filibuster shouldn’t be jettisoned simply because it’s inconvenient to the majority party’s goals,” said Common Cause President Chellie Pingree. “That’s abuse of power

What a difference a change in party control makes, eh?

My expectations are that this lawsuit will be tossed expeditiously.

Here’s the complaint:

Probably the greatest irony there is that Pingree would be able even to grasp the irony.

In any event, the life expectancy of this lawsuit can be measured in days. The government’s upcoming 12b6 motion already has written itself. Hell, the judge’s clerk already might have drafted most of the order dismissing the case. That’s what I would have done. No real need to wait.

Oops, “would not be able to grasp the irony.” I think I just engaged in self-parody. Sigh.

Even if the filibuster were unconstitutional, I don’t see how Common Cause would have standing to challenge it. It would have to come from a Senator, I imagine.

Is it cynical to think this more an effort to keep the filibuster, filibuster proof majority, petard hoisting on originialism, etc alive as topics for the chattering class and obtw, your donations for this vital work are appreciated..

They’re lucky that Burr didn’t challenge them to a dual over it. hahaha

‘

On the merits, the suit is ridiculous. As a means of calling attention to the fact that the filibuster is now so routinely used by the minority party as provide for a situation where all bills require a de facto supermajority, it’s potentially quite powerful.

@Alex Knapp:

“[T]he fact that the filibuster is now so routinely used by the minority party [that] all bills require a de facto supermajority…” is the heart of the argument that the filibuster is unconstitutional. The presentment clause, the quorum clause, the history of the Constitutional Convention’s debates, the history of ratification (three numbers of the Federalist Papers), the general practice of parliamentary procedure at the time the Constitution was adopted and specified exceptions all strongly suggest that the intent of the Constitution is that a bill needs a majority of a quorom to “pass.” The filibuster, embedded as it is by other Senate rules, has effectively changed the Constitution, which the Senate cannot do.