Jack Lew’s Bonus

There's an innocent explanation for giving a huge bonus to a financial exec going into government. And it still stinks.

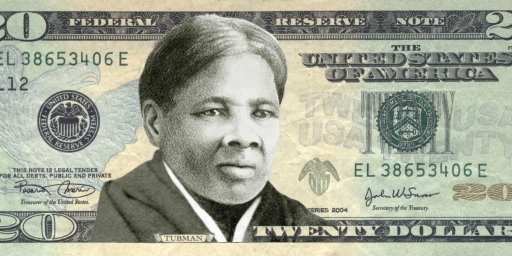

There has been some hubbub over what the WSJ dubbed “Jack Lew’s Golden Parachute.”

The terms of Mr. Lew’s original employment contract with Citi included a bonus guarantee if he left the bank for a “high level position with the United States government or regulatory body.”

Most companies include incentives for top employees not to leave, but in this case the contract was written to reward Mr. Lew for treating the bank like a revolving door. Citi says it likes to accommodate employees who do public service or work at nonprofits. But the Lew contract was specific about a senior job in the federal government. There would be no special payout if he left to run the Red Cross or the New York state budget office.

Citi has been an especially nice landing spot for big-shot Democrats. Former White House budget director Peter Orszag is now a Citigroup vice chairman and somehow finds time to write a column for Bloomberg News. And there was former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, who was paid more than $115 million while encouraging the risk-taking that would have destroyed Citi if not for a taxpayer rescue.

Mr. Rubin was Mr. Lew’s patron at the bank. Mr. Lew’s contract suggests that Citi knew from the start that Mr. Lew was headed back to a powerful job in Washington, and that it wanted him to remember the bank fondly when he left. We have nothing against people making a living, but when they show up a few years later to do more “public service,” taxpayers have a right to know what their private employers were paying them to do.

Even Kevin Drum found this “odd” and he mused, “Lew is a certified budget genius with many years of government experience, so it’s hardly a surprise that Citi expected that he might leave at some point. Still, what innocent explanation is there for actively encouraging him to leave? I’d certainly like to hear the reasoning behind this.”

UCLA’s Mark Kleiman, an “old friend” of Lew’s, says it’s pretty simple:

Pay for senior jobs in big financial services firms consists of salary plus bonus, with the bonus being a large part of the total. If the employee stays at the firm, the bonus decision may be fraught with tension, but it’s reasonably straightforward ethically: the bonus is intended to reward performance in the past and keep the employee working hard in the future.

If the person leaves, or announces the intention to leave, before the bonus is paid some year, the forward-looking justification for paying a bonus disappears, and the firm has to decide whether it wants, in effect, to hand the departing employee a gift, or instead cheap out and punish him for leaving. That’s life in the big city; as a result, people are likely, if they have a choice, to wait until they have last year’s bonus in hand before announcing their intention to leave.

Now imagine that someone in such a job gets an offer to take an important post in one of the federal agencies whose actions influence the financial-services industry: the Treasury, or the Fed, or the SEC, and that the offer becomes public before last year’s bonus is paid. (People offered such jobs have very little control over the timing.)

Now the firm has a real problem. Presumably it doesn’t want to cheap out. On the other hand, if it pays a big bonus, it has just made a gift to an official whose decisions will help or harm the firm. Such a payment, even if fully justified by past performance, will have the appearance of a bribe. No such problem would arise if the person left to run the Ford Foundation or the Red Cross.)

So if a firm hires someone with a public-service background and ambitions to go back into government, it makes sense to negotiate a severance bonus up front, specifically in case the person leaves to take a senior Federal job. That way the person is protected against a big financial hit if such a job comes through – otherwise he might want to take a different job now, one that’s not bonus-dependent or one where receiving a bonus wouldn’t create the appearance of impropriety – while the firm avoids the problem of voluntarily either paying or not paying a big bonus to someone who will exercise power over it in the future.

To which Drum responds, “That makes sense. And I’d add something to this: if this is the explanation, then it’s obviously standard practice on Wall Street, something that the, ahem, Wall Street Journal would know perfectly well. But that didn’t stop them.”

Indeed. It’s almost surely common practice and thus “innocent” under the rules of the game.

Still, as I often note in these situations, while neither Lew nor Citi did anything unethical, those “rules of the game” are nonetheless problematic. On the one hand, we really don’t want to discourage our best experts from entering public service. The Jack Lews and Robert Rubins have genuine skills and they’re sacrificing a lot to go into government and work for $179,000 a year. On the other hand, they cash in big time when they hit the revolving door and go back out into private industry. And that creates real problems.

Unlike career civil servants, these guys naturally operate with one eye on their next private sector job. It’s problematic enough in the case of senior executives and general/flag officers who are a couple years away from retirement. But, for appointees, they’re heading back to the big bucks of Wall Street or K Street sooner rather than later.

Lew and Rubin and their kind—and, contra WSJ’s editorial board, Republicans absolutely play the game the same way—come in the door with the best interests of the industry they oversee in mind. That’s not bad faith; it’s a function of their having prospered in that industry’s culture, thus confirming how awesome said culture is. Further, even if they’re persuaded that something about that industry’s practice needs to change in a drastic way, they have to be incredibly reluctant to step on the toes of the people who are going to be bidding for their services in a year or two.

We could, I suppose, prohibit people who serve in these positions from going back into the employment of the industry they regulate for some fixed period. But they’d just go into lobbying. And, if we forbid them from making big bucks in their chosen field for some number of years, they’d simply refuse to go into government service to begin with.

So, we either have to live with this obvious conflict of interest or substitute political appointees with career bureaucrats. And that, surely, isn’t without its own set of problems.

But that concern exists whether he gets a bonus or not.

He got a nice bonus when he left his NYU job busting unions and steering students into overpriced private loans to go to Citibank, which was the bank making the most money off those loans.

Amazingly enough, however, Paul O’Neill didn’t have a similar bonus package with Alcoa. And John Snow didn’t have a similar bonus package from CSX. And Hank Paulson didn’t receive a similar bonus from Goldman Sachs. Each of those men had standard salary, bonus, stock, restricted stock and stock option packages. Astonishing, huh? None of them got a “pre-bribe,” so to speak. Go figure.

In any case, the real issue with Lew is not so much the inchoate-bribe golden parachute, it’s the fact that the unit at Citigroup with which he was affiliated was one of the most flaming toxic business and financial disasters of all time. We’re hiring a guy who first pumped and then short sold subprime mortgages at what then became a de facto insolvent bank, and ultimately what became a taxpayer bailed out bank, to be the next Treasury Secretary? Really? Really?? Geez, we’re in steep decline.

“Lew and Rubin and their kind—and, contra WSJ’s editorial board, Republicans absolutely play the game the same way—come in the door with the best interests of the industry they oversee in mind. That’s not bad faith; it’s a function of their having prospered in that industry’s culture, thus confirming how awesome said culture is.”

I would argue that it is bad faith, on the part of the WSJ. Treating this as some unique practice when it is SOP in order to make it look like the Obama Administration is corrupt shows what hacks write for the WSJ.

This reminds me of Michael Lewis’ The Big Short, which was harshly critical of the quality of government regulators / career bureaucrats when compared to the sharps of Wall Street.

The problem is that the disparity of salary in the banking/finance sector between government and private business has become so immense (and the triumph of the individual over the community so total) that I don’t believe there will ever be a fix (government certainly can’t offer salaries at the private level; and limiting private sector salaries is plainly impossible).

As Madison stated, a society cannot rely on the altruism and fair play of its citizens to create a just society.

@Tsar Nicholas: Paulson received an $18.7 million bonus upon leaving Goldman Sachs. Alcoa and CSX are not financial services firms.

Anybody got a bright idea to stop the revolving door?

I can complain about this with the best of ’em, but what’s the solution?

@Rob in CT: Massive “Revolving Door” tax on their first year or two of salary back in the private sector? Something in excess of 50%, to make sure the bite hurts a bit. That way, we can make sure they pay their fair share.

I think that equating Jack Lew’s career path with Robert Rubin’s is an error. Robert Rubin was a banker who went to work for the Clinton Administration. Jack Lew is a political operative who went to work for a bank and then back into government.

I’ll bite Rob in CT: How about a 3% corporate surcharge per employee hired out of senior Federal positions for up to 3 years? We should also offer senior federal officials a 3 year paid sabbatical after leaving their positions. A rolodex rots pretty good in that amount of time. Enough to minimize influence after going back into the private sector.

@James Joyner

Why would it be a bad thing if people who go into government service do so without the goal of getting rich from it? I can’t think of a better way to screen people than to tell them, “You’ll be comfortable” but you’ll never be wealthy and powerful. Government isn’t here so you can strike it big.”

Robert Rubin and Jack Lew have no knowledge or skills unavailable to much more ethical men and women. We do not, and never have, needed them. One of the weapons the grifter class uses to secure their free ride is to convince others that the grifter is somehow indispensable.

They aren’t.

@Rob in CT: How about a 90% top marginal tax rate on any income above, say ten million? That would sure cut down on the incentives to amass vast fortunes.

Everyone’s always going to be suspect. I wouldn’t bother trying to fix that. Better there should be meaningfully compensated and rewarding career opportunities for regulators be they civil service or, more realistically, private bounty hunters.

@Rob in CT:

A job quarantine required by law.

You dirty Communist…

@Tsar Nicholas: I agree with Tsar, here, for the second time.

James, the specificity of the language doesn’t excuse the bribe at all. He would only get that payment if he took the sort of job where Citibank would want to bribe him.

@Barry: As pointed out in the original article, if Lew had gone off to run the Red Cross (i.e., would be of no further use to Citibank), he wouldn’t have received that bribe.

@alkali: I should have known; Tsar is simply not honest.