Most American College Students Don’t Borrow To Pay Tuition

Some surprising findings about how America's undergraduates are paying for their education.

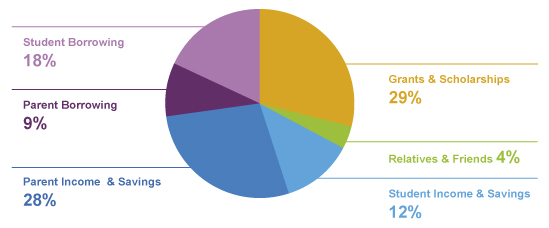

Andrew Sullivan points to this Sallie Mae survey of how American undergraduates (which they define as students between the ages of 18 and 24) pay for their college tuition. The results are not what you’d expect given all the attention given to rising college tuition and student loans:

- 83% of college students and parents strongly agreed that higher education is an investment in the future, college is needed now more than ever (70%), and the path to earning more money (69%).

- Drawing from savings, income and loans, students paid 30% of the total bill, up from 24% four years ago, while parents covered 37% of the bill, down from 45% four years ago.

- The percentage of families who eliminated college choices because of cost rose to the highest level (69%) in the five years since the study began. Virtually all families exercised cost-savings measures, including living at home (51%), adding a roommate (55%), and reducing spending by parents (50%) and students (66%).

- In 2012, families continued the shift toward lower-cost community college, with 29 percent enrolled, compared to 23 percent two years ago. In fact, overall, families paid 5 percent less for college compared to one year ago.

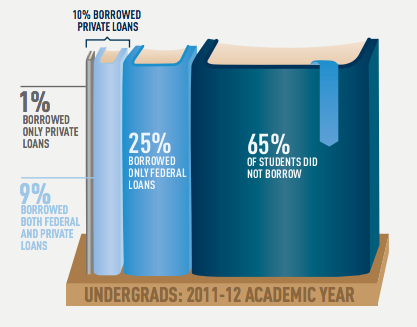

- 35% percent of students borrowed education loans to pay for college: 25% borrowing federal loans only, 9% using a mix of federal and private loans, and 1% tapping private loans only.

As always, charts are helpful in understanding this data:

Sallie Mae also produced an infographic, one part of which does a very good job of summarizing the findings:

Kay Steiger looks at this data and concludes that this means that most American ungrads are still “wealthy”:

This indicates to me that the vast majority of those attending college (and it’s worth noting that Sallie Mae defined “undergraduates” for the purpose of this survey as 18 to 24 year olds, who are very much the “traditional” college student) are people who can afford to do so without taking out loans, which means they’re wealthier. There are still some low-tuition schools out there that you can attend without taking out vast amounts of loans if you don’t have wealth or savings, but that’s an increasingly small portion of colleges these days. What this second chart indicates to me is that our traditional “undergraduate” population is still relatively wealthy. This means that college is less a means of class mobility as it is a means of maintaining one’s class.

I am not sure that this is an accurate conclusion. For one thing, it’s worth noting that the study itself appears to include students both four-year and two-year colleges and was weighted so that it was getting representative samples from both types of institutions, as well as from all sizes of institutions. For smaller schools and two-year institutions, tuition is obviously going to be far lower than a four-year public or private university. Additionally, discounts for in-state status and other benefits may reduce the cost of tuition at some institutions for some individuals. Keeping this in mind, isn’t it also likely that a sizable portion of that part of the student body that is not using loans to pay tuition are using either savings or working their way through school, perhaps only taking as many credits as they can afford to pay for in a given year?

Steiger doesn’t make clear what her definition of “wealthy” is either. Does she consider a middle-class family that, thanks to savings and perhaps some good fortune during the real estate boom was able to afford to pay for their child’s education “wealthy,” because I’m pretty sure that family wouldn’t. Steiger makes a very broad conclusion here based on the data, but it strikes me that we’d need to see further research into the income status of the families of these students before being able to conclude if she’s correct. My guess, though, is that she isn’t.

These finding also raise interesting implications for the debate over tuition and student loan debt that we’ve been dealing with in this country. Quite obviously, we’re talking about a minority of the student population here, and while I’m not suggesting that this means we can ignore problems like the Higher Education Bubble, but it does suggest that we ought to keep in mind that, for the vast majority of American college students the student loan issue isn’t really much of a concern. Perhaps what we should do is find a way to bring the cost of Higher Education down so more people can join the group of students that don’t borrow.

Here’s the study itself for those interested:

I like this:

For what it’s worth, this is a pretty good recapitulation of my views on long term trends:

The Siege of Academe

If you want to go to a selective four-year college and can do it without taking out a loan or relying on scholarships, you are way wealthier than normal Americans.

I just looked up Miami of Ohio, where humble Paul Ryan went. Instate tuition and room and board is 24K. Out of state is 39K.

Median income is around 50K. Do the math. There’s an enormous gulf now between people who have the wealth to make a play at the middle-class American Dream and those who do not.

The University of California at Berkeley now has annual tuition costs of over $12,000, and when you factor in housing, books, and other costs the annual tab is about $25,000. This is still about half the annual cost of attending a private liberal arts college. I was able to work summers and pay for my UC education without borrowing – that is not possible any more.

When my daughters were applying to colleges I told them both that they could attend a private college if they could make the cost to me = to that of attending the University of California – that is get scholarships and work-study to cover over half the cost and we can do it. They attended liberal arts colleges, got very good scholarship offers + work-study, and we are able to make it happen. Still, it cost a lot of money even with that deal. In total we paid for at least 1/3rd the total cost of the girls’ college education.

One thing those figures suggest is that there’s not going to be a whole lot of sympathy for students and former students who are looking for ways to avoid paying off their loans. If the majority of families are shouldering the burden of tuition, they’re going to see ‘free riders’ in a very negative light.

@John Burgess:

Hear hear.

I don’t think the study’s findings are quite what are being represented. I think that the study finds that the lower your family’s income the more likely your are to borrow but the less likely you are to go to college.

We have a conflict. How much of public higher education does tuition pay for? The balance, the taxes that pay for public higher education are regressive.

One thing that this study doesn’t seem to make clear is how the FAFSA works. If you are under 25, the odds of you being able to declare yourself an independent student (and thus apply for federal aid using only your income) are very low: you need to be (among other categories) married, a veteran, a ward of the state when you turned 18, or an emancipated minor. Otherwise you have to include your parent(s)’ income in your student aid filing.

This causes a lot of people to delay college and/or go to college part time, because aid is less available to them than it would be otherwise. Raising the default age of independence to 25 results in only the poorest and those in higher income brackets and/or with significant savings heading to college in a “traditional” time line.

It’s actually not surprising that college-bound people today are being more careful about incurring student loan debt. All throughout their high school years they’ve been living through difficult economic times. I’m sure that many of them have heard horror stories, sometimes from older siblings, about graduating with massive debt loads and no job prospects. It’s sort of the way, though in a very different context, that the crack epidemic of the early 1990’s faded away, as a new generation started to see the ruin that crack had wrought on those a few years older.

I don’t know if this can be demonstrated statistically, but my guess is that the people who entered college in 2005, 2006 and maybe 2007 are the worst off. They would have entered college when the economy was still doing well, and when even liberal arts graduates were getting decent jobs, but by the time they graduated things had gone sour and their degrees counted for little. Some might have been able to switch to more marketable majors while partway through college, but that isn’t always feasible. Try changing your major from literature to petroleum engineering after your sophomore year – barring a miracle it’s not going to happen.

@Peter:

This Mark Cuban essay is a fairly bracing piece in a similar vein.

My daughter opted for a state university because of in state tuition reductions so her loans would be less. The difference between the state university she attends and other financial aid packages was about 7,000 or more dollars per year.

I think more and more students are shopping a little more wisely when choosing colleges and universities. I know several classmates of my daughter’s opted to attend the 2 year community college because it was more affordable.

@al-Ameda:

Similar experience. I worked 60 hrs./week to put myself through Michigan (part-time) and worked half-time while going to Cal for grad school. Given the in-state tuition fees & related costs at both schools today, to say nothing of basic living expenses, and the wages I could get for the same kind of jobs I held, it would be impossible to support myself and attend either school.

No backup statistics here, but my sense is that it is kind of a perfect storm. Wages have, relatively speaking, stagnated or decreased significantly at the same time that state-funded universities have had to replace state support with higher fees.

I’ve got a kid in 10th grade, which means I have maybe another year, year and a half before I have to start worrying about this. Who knows, I could get lucky and an asteroid hist the earth before then.

Also some of the more selective state universities are accepting fewer instate students because the out of state tuition is higher and brings in more income.

When I went to college back in the late 80’s a person could easily work and pay for their tuition-in state tuition was less than 1,000 dollars a semester, the same university I attended is now around 6,000 a semester in tuition. That doesn’t include room and board which has also increased significantly.

It also doesn’t help that the college education funds have taken three huge hits in the last 11 years.

My college was paid about 60-30-10 Pell Grant/Work Study/Loans. The work study set me back 2/3rds of a year but it was worth it. I earned by own keep during the whole period (1983 – 1988).

No college degree is worth crippling debt, not in 2012 when all the world’s knowledge is a click away.

There are other ways. The lion’s share of my college tuition was paid by tuition reimbursement programs from my various employers over many, many years. In all it took more than 25 years to finish my BA, but it was completed with zero debt, and summa cum laude.

I now believe that the slow pace and embedded ritual of those many years of homework and general academic rigor made me a more curious and reasoned 40-something year old than I would have been taking the traditional route of a kid just trying to get through it.

Doug,

So how can it be that, “*(65.6%) of 4-year undergraduate students graduated with a Bachelor’s degree and some debt” (finaid.org) and “for the vast majority of American college students the student loan issue isn’t really much of a concern?”

I would say that the data provided by Sallie Mae is highly misleading.

First, Sallie Mae includes the entire community college population without regard to educational outcome. There are many people who will pay or get financial aid to take a few community college courses and never go beyond that. The degree completion rate for community college students is pretty horrendous: completecollege.org

From Sallie Mae’s own data we can see that only 22% of these students borrowed as compared to 48% and 63% of students that borrowed at 4 year public and private universities respectively.

Which brings us to:

Second, how many of those students that do complete community college end up borrowing money when they reach the university level? The entire Sallie Mae report suffers, or I should say that the conclusion you draw is erroneous, because it is just a snapshot in time. It tells us nothing about the percentage of students that graduate with debt.

*This data is for 2007-08 but 65.6% is an increase from 64.5% for 2003-04. 2007-08 is the latest hard data I could find but this report also estimates around 65% for 2010: http://projectonstudentdebt.org/files/pub/classof2010.pdf

All the more reason for Uncle Fed to get out of the student loan business. We don’t need to be spending a single penny of federal taxpayer dollars on college educations. With rare exceptions it’s a waste of money. The kids don’t need it. They have other sources. The schools themselves can fill in whatever gaps remain.

@Tony W: Unfortunately, that only works if you’re not dealing with brain-dead HR people who insist you have a B.A. before you even apply for a position….

It’s far too easy to use the existence or lack of a degree as a sorting mechanism when going through resumes, no matter what you have learned from experience.

(Remember that HR people never want to hire people; they’re always looking for excuses to throw out your application. Hiring you would just create more work for them and be a risk if your hiring doesn’t work out. Better remain in the “searching for a perfect candidate mode.”)

@Tsar Nicholas: I used to believe in students loans but over time have become less and less enamoured of them. If one starts digging into the numbers, it looks like the lion’s share of the increase in tuition has gone for better facilities and the huge sandwich of middle-management that now clutters most universities. I don’t know where this got started (bureaucracy usually expands to use up available $$$) but wonder if the increasing population of helicopter parents demanding the best for their darlings wasn’t a big reason.

Students used to live in pretty crappy housing and live off cheap food. It was a great training ground for living off your first salary. What happened?