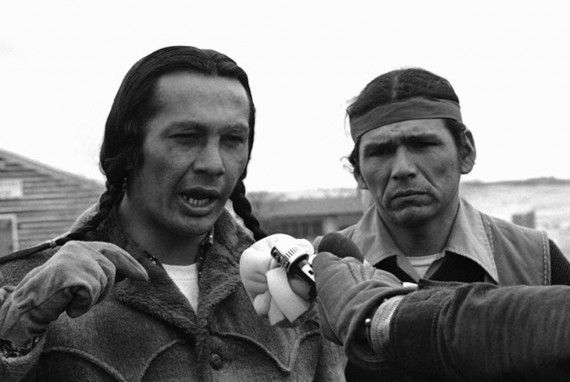

Russell Means, Native American Activist, Dead At 72

Russell Means, the Native American activist who founded the American Indian Movement and became famous for leading a standoff with federal authorities at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, has died:

Russell C. Means, the charismatic Oglala Sioux who helped revive the warrior image of the American Indian in the 1970s with guerrilla-tactic protests that called attention to the nation’s history of injustices against its indigenous peoples, died on Monday at his ranch in Porcupine, S.D., on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. He was 72.

The cause was esophageal cancer, which had spread recently to his tongue, lymph nodes and lungs, said Glenn Morris, Mr. Means’s legal representative. Told in the summer of 2011 that the cancer was inoperable, Mr. Means had already resolved to shun mainstream medical treatments in favor of herbal and other native remedies.

Strapping, ruggedly handsome in buckskins, with a scarred face, piercing dark eyes and raven braids that dangled to the waist, Mr. Means was, by his own account, a magnet for trouble — addicted to drugs and alcohol in his early years, and later arrested repeatedly in violent clashes with rivals and the law. He was tried for abetting a murder, shot several times, stabbed once and imprisoned for a year for rioting.

He styled himself a throwback to ancestors who resisted the westward expansion of the American frontier. With theatrical protests that brought national attention to poverty and discrimination suffered by his people, he became arguably the nation’s best-known Indian since Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

But critics, including many Native Americans, called him a tireless self-promoter who capitalized on his angry-rebel notoriety by running quixotic races for the presidency and the governorship of New Mexico, by acting in dozens of movies — notably in the title role of ”The Last of the Mohicans” (1992) — and by writing and recording music commercially with Indian warrior and heritage themes.

He rose to national attention as a leader of the American Indian Movement in 1970 by directing a band of Indian protesters who seized the Mayflower II ship replica at Plymouth, Mass., on Thanksgiving Day. The boisterous confrontation between Indians and costumed “Pilgrims” attracted network television coverage and made Mr. Means an overnight hero to dissident Indians and sympathetic whites.

Later, he orchestrated an Indian prayer vigil atop the federal monument of sculptured presidential heads at Mount Rushmore, S.D., to dramatize Lakota claims to Black Hills land. In 1972, he organized cross-country caravans converging on Washington to protest a century of broken treaties, and led an occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He also attacked the “Chief Wahoo” mascot symbol of the Cleveland Indians baseball team, a toothy Indian caricature that he called racist and demeaning. It is still used.

And in a 1973 protest covered by the national news media for months, he led hundreds of Indians and white sympathizers in an occupation of Wounded Knee, S.D., site of the 1890 massacre of some 350 Lakota men, women and children in the last major conflict of the American Indian wars. The protesters demanded strict federal adherence to old Indian treaties, and an end to what they called corrupt tribal governments.

In the ensuing 71-day standoff with federal agents, thousands of shots were fired, two Indians were killed and an agent was paralyzed. Mr. Means and his fellow protest leader Dennis Banks were charged with assault, larceny and conspiracy. But after a long federal trial in Minnesota in 1974, with the defense raising current and historic Indian grievances, the case was dismissed by a judge for prosecutorial misconduct.

Mr. Means later faced other legal battles. In 1976, he was acquitted in a jury trial in Rapid City, S.D., of abetting a murder in a barroom brawl. Wanted on six warrants in two states, he was convicted of involvement in a 1974 riot during a clash between the police and Indian activists outside a Sioux Falls, S.D., courthouse. He served a year in a state prison, where he was stabbed by another inmate.

Mr. Means also survived several gunshots — one in the abdomen fired during a scuffle with an Indian Affairs police officer in North Dakota in 1975, one that grazed his forehead in what he called a drive-by assassination attempt on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1975, and one in the chest fired by another would-be assassin on another South Dakota reservation in 1976.

Undeterred, he led a caravan of Sioux and Cheyenne into a gathering of 500 people commemorating the centennial of Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s last stand at Little Big Horn in Montana in 1876, the nation’s most famous defeat of the Indian wars. To pounding drums, Mr. Means and his followers mounted a speaker’s platform, joined hands and did a victory dance, sung in Sioux Lakota, titled “Custer Died for Your Sins.”

After his political days were over, Means started on a new career:

Mr. Means began his acting career in 1992 with “The Last of the Mohicans,” playing Chingachgook opposite Daniel Day-Lewis and Madeleine Stowe in Michael Mann’s adaptation of the James Fenimore Cooper novel. Over two decades he appeared in more than 30 films and television productions, including “Natural Born Killers” (1994) and “Pathfinder” (2007). He also recorded CDs, including “Electric Warrior: The Sound of Indian America,” (1993) and wrote a memoir, “Where White Men Fear to Tread” (1995, with Marvin J. Wolf).

Rick Moran has an interesting comment about Means’ legacy:

Means’ activism served a large and worthy purpose by calling attention to the miserable plight of Native Americans. Recent years have seen tribes running casinos on their reservations (“like the buffalo returning” quipped one Native American leader) and while the gambling houses raise millions, still not enough is being done by tribal councils and the US government to lift the poorest of the poor out of abject poverty. In 2010, the poverty rate on reservations was 28.4 percent, compared with 22 percent among all American Indians (on and off reservations), and 15.3 percent among all Americans. This is an intolerable state of affairs and Means tried his utmost to call attention to it.

More than fighting poverty, Means fought for dignity. It seems trite and vainglorious to say that someone fought for an intangible like dignity, but in the case of Means and Native Americans, it is true. Certainly the helplessness born of the indignity of reservation life is a contributing factor to poverty. Did Means change that dynamic? He definitely inspired younger Native Americans to take up the cause and the pride of heritage he infused in them will pay dividends in years to come. The entire American Indian Movement — violent and racist as it was at times — has been a source of inspiration to the generations born since the 1960’s. When weighed on the scales of history, AIM will probably be considered an overall plus for instilling racial values in the young and attempting to preserve Native American culture.

His rhetoric was often over the top and confrontational, but Russell Means brought America’s attention to a people who had largely been ignored or treated as a novelty act ever since they were pushed onto reservations. For that, at least, he deserves credit.

Russell Means was an American. Nothing more need be said. (Americans are… complicated.)

While I know Russell Means was quite a polarizing figure, I can’t imagine NOT recognizing his accomplishments for Native Americans. True, he may have done things that were, at the very least, questionable in nature, and, at the very worst, reprehensible in more ways than one. However, he drew attention to his missions, by way of strong actions, tough words, and sometimes violence. I wish I had gotten to know his story better. My mother had met him on several occasions. She told me how potent his presence was. She also told me that she, like so many others, was captivated by his words. My mother was an activist, battling for TWLF (Third World Liberation Front) in Northern CA, then the Alcatraz Occupation, and she had many friends in AIM. I was very young and remember her being gone a lot. When she got home, she had many stories for me. She would bring me bracelets – I unpacked those a few months ago, just about five years after her death. I guess what I am trying to say is that I never fully understood activism until years later…when I became a young woman -and somewhat of an activist- myself. The point here is that in order to be heard, reach goals, and impart knowledge on people, some feelings -and worse- may be hurt. More importantly, rather than choosing our heroes, we need to choose our beliefs. I am not ambivalent about Russell’s death; I am sad. It leaves me with a feeling of emptiness that just hangs in the air. I see our Native American modern-day warriors slowly becoming our Native American elders, and it makes my heart heavy. There is so much to be learned from these people…so much about their past, the present, and what we can do together in the future, that any opportunity cannot be overlooked. I would give anything to have those we lost back -even just briefly- so I can finally be taught the truth.