Should Juror’s Identities Ever Be Kept Secret?

Until the presiding Judge in the case rules otherwise, the identities of the members of the jury in the Zimmerman is secret. Should that be the case?

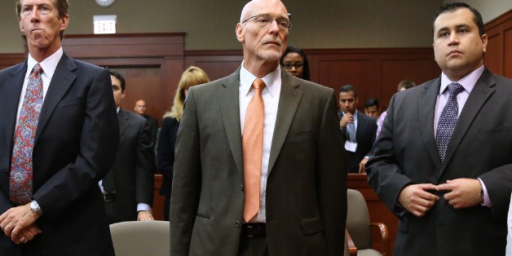

Throughout the George Zimmerman trial, the six women plus three alternates that made up the jury were known only by a letter and a number. Now that the trial is over, their anonymity remains secure for at least the next six months unless individual jurors choose to identify themselves publicly. So far, that has not happened. Indeed, the one juror who did become public via an interview with CNN’s Anderson Cooper was identified only by her Court designation, Juror B-37. A columnist for The Orlando Sentinel, though thinks that the jury’s names should be made public as soon as the trial is over:

Trial watchers became accustomed to referring to the women by their letter and numerical codes during the five weeks of jury selection and testimony.

Now that the trial is over, we ought to know their names.

I’m not advocating that these women become targets of anger over their not guilty verdict — I think they made a sound decision based on the law.

And I’m not suggesting that the jurors be pressured to talk if they choose not to.

I am saying that judges have no business keeping juries anonymous once a trial is over.

Secrecy has no place in a court system founded on openness.

Probably no surprise coming from a newspaper columnist.

(Full disclosure: My employer, the Orlando Sentinel, is arguing in court for the jurors’ names to be made public. The judge hasn’t ruled.)

Questions about anonymous juries aren’t as sensational as Zimmerman getting his gun back. Or Rachel Jeantel’s reaction to Don West’s ice cream cone photo.

But there are reasons why everyone should care about making sure juries aren’t kept in the shadows.

Plain and simple: Secret juries undermine public confidence in the system.

The right to a jury trial is as fundamental as the other civil liberties also enshrined in the Constitution.

The Founding Fathers intentionally set up the jury system — panels of everyday people to judge guilt. What a stark contrast to the secretive Star Chamber courts that colonists left behind.

When juries aren’t open to scrutiny, the American legal system is asking for trouble.

On its surface, I suppose, there is a persuasive element to this argument on some level. As a general rule, there’s something that just feels wrong about the idea that an essentially anonymous group of people are judging the innocence or guilt of a person on trial for their freedom or their life. It smacks of the Show Trials of the Stalinist era in the Soviet Union, and it suggests a lack of accountability that ought to concern anyone who is interested in a properly functioning judicial system. Indeed, in most cases, nobody unconnected with the case is going to care about the identity of the members of a jury in the average criminal case. It’s likely only to be high profile cases where this would not be the case, and in those cases it’s primarily members of the media, interested mostly in interviewing jurors about what led to their decision, who are going to want to know who was on the jury. Arguably, there is a public interest in finding out the reasoning behind a controversial jury decision in a high profile case as well.

However, there are also compelling reasons for keeping the identity of jurors secret well beyond the conclusion of the trial. The most obvious, of course, would be the safety of the jurors themselves. In cases that are controversial like the Zimmerman case, or those dealing with the trial of Defendants, or their associates, who may potentially seek revenge on a jury that returned a guilty verdict, or may seek to harm or intimidate jurors into making claims post-verdict that make it appear as though there was something improper about deliberations that would enable a conviction to be overturned. This is why you often see jurors in cases dealing with organized crime and terrorism have their identities placed under seal for an indefinite period of time. Interestingly, though, the author cites one of those cases as an argument against anonymity:

Consider the case of John Gotti.

The Mafia leader was acquitted of racketeering by an anonymous jury in 1987.

Five years went by before it was discovered that one juror had Mafia connections and took a bribe to push for an acquittal.

Perhaps if the jury had not been anonymous, the truth about the rogue juror would have been discovered sooner — or the bribe wouldn’t have happened at all because the risk of scrutiny would have been too great.

This argument doesn’t really make any sense, though. The corruption of the Gotti jury quite obviously occurred before the trial even started so it’s unclear how a lack of post-trial anonymity would have broken a jury corruption case any earlier than it was actually broken. Furthermore, it’s worth noting that even when juror identities are secret, there are still a group of people who have access to them including the attorneys in the case, court personnel with appropriate clearance to have such information, and in proper circumstances depending on the relevant jurisdiction, law enforcement. If there is evidence of jury corruption, discovering the identity of a specific juror in a specific case would be relatively easy for those investigating the matter to uncover. So, the example of the corrupt Gotti juror doesn’t strike me as a compelling argument against juror anonymity.

The final argument against permanent juror anonymity, of course, is a freedom of the press argument. Advocates of this argument would argue that the public has a right to know the basis of a jury’s decision in cases of public interest such as the Zimmerman trial that outweighs the individual juror’s privacy interests. As a strong First Amendment advocate, I am somewhat sympathetic to this argument but, at the same time, I see a compelling competing interest in at least allowing individual jurors to be the ones who decide whether or not their identities are revealed.

Just look at the Zimmerman trial. Just five days after the verdict was rendered, there have been protests in several cities and a sit-in at the Florida Governor’s office. If the juror’s identities were known, does anyone doubt that there would currently be protests outside their homes or places of business? Or that some irresponsible people would be making threats, or worse, against people who did nothing more than respond to a summons to perform their civic duty, sit through a long trial during which they were separated from their families, and render a verdict based on the facts and the law that even many of the people who are disappointed in the outcome admit was the correct one under the circumstances? More importantly if that’s what happens in a case like this to jurors, then what does that say to the next group of people summoned to potentially be part of a politically controversial, high profile case?

It seems to me that the best way to balance things here is to leave the matter of anonymity to the judge to deal with on a case by case basis, which is essentially the case in Florida. Perhaps there will be a time when the identities of the Zimmerman jurors should be made public, but even when that happens it should ultimately be a matter in the control of the individual juror. Let the Court contact them and make the choice of whether or not they want their identity made public. If they say no, then let it be anonymous forever if that’s the case. Otherwise, we risk the possibility that nobody will want to serve on a controversial case for fear of being hounded to death by the media and by media blowhards like Al Sharpton because they did nothing more than what the State of Florida asked them to do.

It’s also worth considering that none of these people volunteered for jury duty. I can understand an argument that they shouldn’t be forced to surrender their privacy because of a combination of bad luck and an inability to wriggle out of it.

There’s a Kill Zimmerman Facebook page that Facebook has refused to take down. Protesters have already attacked a family rushing a child to the hospital. And “Justice For Trayvon” “peaceful protesters” have already looted one Wal-Mart.

There are several other stories, but they haven’t been as well substantiated as yet.

So let’s give the mobs even more targets, shall we? Let’s show future jurors what they can expect if they don’t give up the “right” verdict.

@Jenos Idanian #13: Riots in Oakland and LA, fires, destruction of property, and the burning of the US flag!! Most of the media is either ignoring or downplaying it, but some stations are picking up on it. Many have started to move on to other stories: Rolling Stone outrage, Kanye West, and the Jackson trial.

As a practical matter, I don’t see how you can keep this information from the public anyway. I would imagine that many people watching the trial new exactly who some of the jurors were, and any of those people could have identified the juror to news media if asked.

@Joe Reed: Excellent point. The jury system is endangered by the difficulty to get good jurors, particularly for lengthy trials. I’ve seen a prospective juror, who had been called for potential jury duty several years after serving on a big, lengthy political corruption trial, whom one would describe as in SHELLSHOCK by the prospect of being on another jury.

I really see no public interest in the public access to juror identity, particularly in a televised trial. If criminal defense attorneys need to interview jurors for potential appellate issues, yes, under the supervision of the courts.

I consider this as being similar to a secret ballot, with similar justifications.

Also, what happens if potential jurors start refusing to take the oath on account of their fear of post-trial retaliation making them incapable of rendering an impartial verdict?

In high-profile cases especially, and even in general, I am okay with keeping juror identities secret. The potential backlash and danger to jurors who served is one concern, the other is the potential chilling effect if anything were to happen to one of them–or even if it causes people to think twice about serving.

We NEED good, solid, dedicated citizens to serve on juries. Protecting their identities in the aftermath of an emotionally-charged case is a very small price to pay.

@Stormy Dragon: Good point. Plus, even in cases that are lesser profile than the Zimmerman case, jurors are likely to try even harder to get out of jury duty than they do now. Getting a good, impartial jury of one’s peers is hard enough now. If people fear for their safety, it will only be worse.

Except that they’ll be distracted by some other shiny object, there is nothing the media can’t do in November in regards to the jury that they can do now. Sure, the rectal exams won’t be timely and people may not care anymore so they won’t get the eyeballs but so what. if there is something nefarious about the jury, then it’ll be a fresh story in 6 months for the media.

This columnist is just trying to sell papers and doesn’t want to let the juicy jury material marinate and miss the feeding frenzy.

Don’t worry, this verdict did that already.

As to the jurors keeping their anonymity, of course. They did a tough and thankless job, let them move on with their lives.

@OzarkHillbilly: Just how does one say the jurors “did a tough and thankless job” by rendering a verdict that undermined public confidence in the system?

Sounds like you’re trying to have it both ways here. The jurors got it totes wrong, completely screwed the pooch and borked the system, but they should be thanked for their hard work.

@Jenos Idanian:

No, it sounds like you are still your completely clueless self. Bad laws make for bad results. I suppose that is a concept beyond your limited imagination.

You didn’t say “the law” undermined the confidence, you said “the verdict.” Don’t blame others for your own inarticulateness.

I’m with Charles Barkley. The jury got it right. This was a tragic incident, George Zimmerman made some poor decisions, but he didn’t commit any crimes. And he sure as hell didn’t commit murder as defined by Florida’s laws.

@Jenos Idanian:

You’re right. He didn’t commit murder. He committed manslaughter.

The idea that anyone should be able to assert self-defense in response to a chain of events that they initiated is laughable.

Zimmerman’s actions may not have been criminal, but they WERE contributory. They precipitated and instigated the chain of events which led to Martin’s death. Self-defense in that context is off the table IMO.

Because, let’s face facts here – if Zimmerman had shot a white Eagle Scout, he’d be in prison now. Without…. A…. Doubt …

And you’d be falling over yourself proclaiming that he should be there.

@HarvardLaw92: There’s a word missing from your argument — “reasonable.” As in, a reasonable response to one’s actions.

Is it reasonable to expect that if I follow someone at night from a discreet distance, that they will turn around and try to kill me? No. Similarly, if I’m crossing a street and drop a quarter, it is not reasonable to expect that a child will see the quarter, run out into traffic to get it, and get hit by a car.

@Jenos Idanian:

You miss the fun part. Under Florida law, all I have to do is BELIEVE that you represent a danger. If you’re following me, and I believe that you intend to harm me, I can kill you.

Luckily for me, you won’t be around to refute my story, and luckily for me, the law is written to basically take me at my subjective word. The standard in Florida isn’t what a reasonable person might think; it’s what I say I thought right before I shot you. Entirely, 100% subjective, and all I have to do is convince a judge – boom! – home free.

That’s the really fun part. If Martin had killed Zimmerman, he’d have had an excellent self-defense argument for doing so. In fact, his argument would have been more powerful that Zimmerman’s was. Hell, the man was following him at night, and actually had a gun!

😀

It’s a fricking joke.