Copyright Office: Monkey Selfies Not Entitled To Copyright Protection

The Copyright Office says that works not "created" by humans are not entitled to copyright protection.

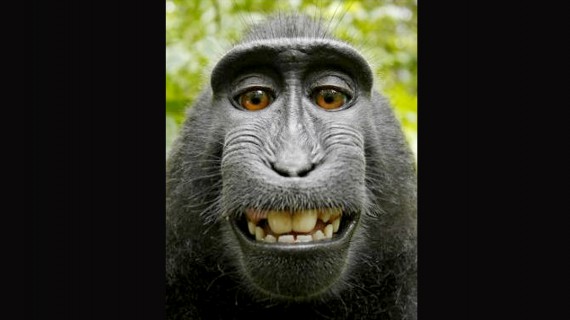

Earlier this month, I noted that a legal dispute had developed between Wikipedia and photographer David Slater over whether or not Slater could claim a copyright in a picture that had been taken essentially by accident when crested black macaque came upon a camera that Slater had left unattended in an Indonesian forest on 2011. Wikipedia claimed that the photograph is in the public domain because it was not taken by a human being, and the law seemed to agree with them notwithstanding The Volokh Conspiracy’s David Post notes that the U.S. Copyright Office has apparently settled this issue once and for all:

The Copyright Office has now weighed in on the question of whether the now-famous “monkey selfie” is protected by copyright (see my earlier postings here and here) with a resounding “NO.” ”Materials produced solely by nature, by plants, or by animals are not copyrightable.” . . . [T]he [Copyright] Office will refuse to register a claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work.”

In reality, the Copyright Office ruling doesn’t end things in what I suppose we should call The Case Of The Monkey Selfie. The publication that Post links to above — which is over 1,000 pages long — is meant to set forth the general guidelines under which the office will issue a copyright to someone who applies for one. If Slater did try to copyright this photograph then, his request would most likely be denied. However, the office’s determination is merely its own interpretation of the law rather than a final ruling on the matter. If Slater pursues his case in Court, the outcome could be quite different. He could, for example, make the argument that the fact that he set the camera that took the picture is enough human interaction to make the photograph something “created” by a human. Whether a court would accept that argument is an unknown issue in no small part because this would seem to be an issue of first impression for any court that heard the matter.

As Post goes on to note, the Copyright Office’s definition of what is and is not entitled to copyright protection has implications well beyond the somewhat silly example of the monkey selfie:

The Report goes on to state that musical works, for instance, like all works of authorship, must be of human origin; thus, a work created by solely by an animal would not be copyrightable, nor would a work, more plausibly, generated entirely by a mechanical or an automated process. And similarly, a choreographic work performed by animals, machines, or other animate or inanimate objects is not copyrightable. These are the kinds of things copyright lawyers are going to be fighting about more and more, take my word for it, over the next few years as claims involving AI programs and similar non-human agents get more valuable and more common.

There would be a difference, of course, between a work created by a human being using a computer and one strictly created by a computer without direct human interaction. Arguably, of course, one could make an argument that the creator(s) of the software that powered the computer would have some kind of claim in the output of its work, although this would be somewhat nonsensical since nobody believes that the creators of Excel have a claim in a spreadsheet their program creates, or that the creators of Photoshop have a claim in the altered photographs the program creates. As we get closer to Artificial Intelligence, though, and computers that are able to “think” and create visual or audio works on their own, then this is likely to become more of an issue. Under the the Copyright Office’s current definition, such works would not be entitled to copyright protection and would be in the public domain free for anyone to use without compensation or credit. Arguably, this would reduce the incentive for scientists and researchers to make advances in these fields, which is kind of what the Copyright laws are supposed to encourage to begin with. At some point, though, it seems clear that both courts and Congress will have to deal with the issue, including the rather important question of who would “own” the copyright on something created by a machine and who would be entitled to the benefit of the license fees that holding the copyright would entitle someone to charge.

When the robots and computers start hiring lawyers, then we’ll know we need to deal with this issue.

No monkey selfies, eh? I guess the majority of commenters here will just have to get used to being ripped off.

Thanks Obama!

I would love to see the Socialcons to use the argument that since Political Speech and Pornography are so vital to preserving the Freedom of Speech that they are not entitled to Copyright Protection.

The thing here that is troubling is that there is usually more to a photograph than simply pushing the button…which is all the monkey actually did.

The image would never have come to light if the person who owns the camera hadn’t:

traveled to the location where the monkey was

placed the camera where the monkey could reach the shutter button

recognized the uniqueness and value of the image

culled it from all the other images on the memory card

promoted it to wherever it ultimately ended up being published

Now…does all that warrant a copyright? Who knows.

I am curious though…if someone had tried to copyright the image in the name of the monkey from the start…would the copyright office have taken the effort seriously?

@C. Clavin:

He didn’t place the camera though, the monkey stole it and placed it themself. If the photographer had set up the camera on a tripod (choosing the background, lighting, etc.) and the monkey had merely triggered it, the photo would be copyrightable because the photographer would have been responsible for the composition of the shot.

In this case, he had no participation whatsoever beyond providing the equipment. This would be like the camera store claiming ownership of any photographs I take because without them, I wouldn’t have had access to the camera to take the photo.

@C. Clavin:

I’ve been to the grand canyon. That doesn’t mean I have a copyright on any pictures other people took while I was there.

I recognize the uniqueness and value of the Mona Lisa. That doesn’t mean I have a copyright on it.

If I find a box of old vacation photos at a yard sale and like one them, that doesn’t mean I have a copyright on it.

Rodney Dill frequently promotes photos here by showcasing them in the caption contest. That doesn’t mean he has a copyright on them.

@Stormy Dragon:

Sure…but you are stretching to link a bunch of totally un-related events (and complete non-events) to make an argument against what is in fact a unique and singular process. (It’s not even a good stretch, by the way.)

Copyright laws exist

according to a previous post written by Doug.

My point is that creativity exists in the process beyond the pushing of the shutter button. This decision, and your stretch, fails to recognize the process. That’s all.

@C. Clavin:

Because the process wasn’t present in this particular case. Simply recognizing commercial value in an entirely coincidental event after the fact doesn’t mean there was a creative process involved. Another example: there’s a particular type of fossilized coral in certain parts of Michigan called Petoskey Stone that’s quite popular with tourists. Recognizing that the stones are beautiful and valuable, a number of people make money polishing the stones and selling them.

As beautiful as the pattern is, however, its entirely the result of random natural processes. Should one of the stone polishers be allowed to copyright the distinctive heaxgonal pattern and band anyone else from using it without their permission?

From the standpoint of the law, there’s no difference between a glacier with a rock and a monkey with a camera.

@Stormy Dragon:

I suppose you could make bad analogies all day, eh?

As you say…every Petoskey Stone is different and unique due to natural processes. So how would you copyright them? If you took a particularly unique stone and COPIED it…say on a t-shirt…then would copyright law apply?

Before you answer…Rosebud Entertainment currently holds the United States trademark rights to the Pet Rock.

If I dropped my camera and the shutter was accidentally triggered and a fantabulously commercial image came out of it…f’ing-a-right I would copyright it…no matter how random and natural the process.

@C. Clavin:

Thing is in this case the monkey not only pressed the shutter button, it composed the shot. Note that there is nothing in the shot but the monkey’s face that he(she?) helpfully placed there. The picture is notable among other pictures of monkeys only because it was the monkey that took it. The owner of the camera didn’t add anything artistic to the picture, so the owner of the camera isn’t entitled to artistic protections. Now, if down the line we think providing digital cameras to wildlife is something we want to encourage we could expand copyright laws.

strangely, Im reminded of the Singing Dogs, and their version of ‘jingle Bells’.

Clearly, the dogs didnt do all that much to produce the recording.

So does that mean RCA (or whoever owns their catologe, these days) no longer has a valid copyright on the recording? what are the limits, here?

If the photo had been Photoshopped (not by the monkey) then I presume it would be copyrighted.

This is a pretty rare bit of copyright case law that Douglas Adams anticipated when he was considering an infinite number of monkeys with typewriters producing the works of Shakespeare in the Hitchhiker’s Guide To the Galaxy

Several thoughts:

An ironic factor in all this is that the degree to which the macaque, and not Slater, is the one responsible for the photograph is precisely what makes the photo interesting, and Slater must have known this at the outset, even if he hadn’t considered the copyright implication.

Suppose the situation occurred with a human under similar enough circumstances that Slater could claim he “engineered” the whole thing? (This could be a human of any age, but child vs adult could be another legal factor.) Would Slater have the copyright? If we consider it a difference, then it must involve differences between animal and human rights, but in an unusual way because no one it claiming that the monkey has copyright.

If it were a human would a completely different element of law come into play because the original story involves theft on the part of the monkey? If someone steals things from your home and makes art out of them, do they not have copyright?

Regarding artificial intelligence, surely there’s precedent going back a long way — in the 60s, a young Ray Kurzweil appeared on “I’ve Got a Secret” to play some music composed by a program he wrote, and I assume music-composition technology has improved since them. So there must be a case that resolves whether the copyright belongs to the original programmer, or to the user who “pressed the button”, or to no one.

Or maybe it depends on additional factors, such as how much the user fine-tuned the music in the program’s settings. In my opinion, the simplest solution would always give the copyright to the user even if all they did was push a button, but there might be a better legal “bright line” out there.

@Grewgills:

Then you are saying if I dropped my camera and it accidentally took the most beautiful image ever I wouldn’t be entitled to a copyright?

Nonsense.

@C. Clavin: That’s a decent hypothetical. It may seem like nonsense, but based on the Copyright Office’s last sentence, I believe they would rule against you.

“… will refuse to register a claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work.”

Unless you *intentionally* dropped the camera with the intention of it snapping a random shot, you didn’t really create it.

@C. Clavin:

That is likely the case. Why would you deserve copyright protection in that case?

Copyright protections exist to promote creative output. Giving copyright protections for random events does not promote creative output.

@Eric Florack:

Your analogy is ridiculous. If the dogs did the arranging and orchestration, then there wouldn’t be a copyright. If, however, the arrangement and orchestration was done by a human to make a bunch of disparate barks and other vocalizations sound like Christmas music, then there was creative input by a person that should be eligible for protection.