Some Notes on the Ruling and the Dissents in the Texas Abortion case

A few observations on Whole Woman's Health, et al., Applicants v. Austin Reeve Jackson, Judge, et al.

To follow up on my previous post, here is some discussion of the ruling and the dissents in Whole Woman’s Health, et al., Applicants v. Austin Reeve Jackson, Judge, et al.

Given my discussion of the enforcement mechanism in SB8, I found the reasoning, such as it can be ascertained from the short, in the unsigned, 5-4 majority ruling to be of interest.

The five Justice majority (Alito, Coney-Barrett, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Thomas) basically took the logic of SB8, that it was not being enforced by any state official, and used that as a reason not to block the law:

The State has represented that neither it nor its executive employees possess the authority to enforce the Texas law either directly or indirectly. Nor is it clear whether, under existing precedent, this Court can issue an injunction against state judges asked to decide a lawsuit under Texas’s law…Finally, the sole private-citizen respondent

before us has filed an affidavit stating that he has no present intention to enforce the law.

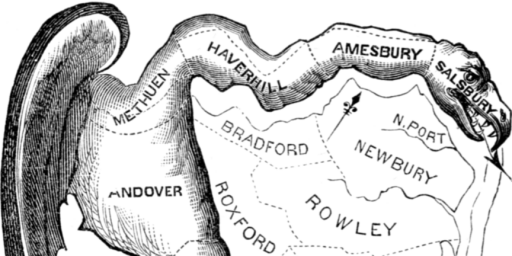

This is pretty stunning. This logic would stop the Court from providing a temporary stay of a law structured like SB8 regardless of what that law allowed contained relief can’t be sought until a private citizen undertook a lawsuit. So, in theory, any constitutional right could be banned in a given state by this legal construct, at least temporarily.

In other words, since SB8 does not rely on state officials to enforce it, there is no way to stop it from going into effect because it cannot be known as to who will be seeking to file suit under the law. This strikes me a dodge, because quite clearly the legislature, a clear agent of state government, is seeking to use the law to achieve a public policy end and the five Justices in the majority know it. To pretend like they can’t do anything is disingenuous. Indeed, the reality is that they like the outcome vis-a-vis abortion, and so are ruling accordingly.

I would note, they are within their constitutional rights to do so, but this ruling rather substantially puts to rest the notion that serious intonations about stare decisis at confirmation hearings are not going to be taken seriously in the future. It is almost cheeky to see the cites to prior cases in the ruling, as it is hard to see this ruling as taking established jurisprudence into account. After all, if precedence can be ignored, why bother to play that game any longer?

Specifically, the ruling cites Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123, 163 (1908) as to why they can’t intervene. As explained by Law Professor Mary Ziegler at SCOTUSblog:

Under Ex parte Young, plaintiffs can seek injunctions against officials who are responsible for enforcing potentially unconstitutional laws, but Texas is doing its best to argue that there is no one to sue.

I find this interesting because the majority feels bound by that established jurisprudence while not feeling bound at all by the rulings in Roe and Casey. Say what you will about SB8, but it is clearly and directly aimed at subverting those established rulings and those rulings would only be overturned by the Court itself or via a constitutional amendment.

Justice Roberts’ in dissent (as joined by Kagan and Breyer) rightly notes:

The statutory scheme before the Court is not only unusual, but unprecedented. The legislature has imposed a prohibition on abortions after roughly six weeks, and then essentially delegated enforcement of that prohibition to the populace at large. The desired consequence appears to be to insulate the State from responsibility for implementing and enforcing the regulatory regime.

This confirms my instinct that the enforcement innovation in the law is, in fact, new and not some unknown-to-me tactic.

Further, Roberts’ preferred approach was the correct one, in my estimation:

The State defendants argue that they cannot be restrained from enforcing their rules because they do not enforce them in the first place. I would grant preliminary relief to preserve the status quo ante—before the law went into effect—so that the courts may consider whether a state can avoid responsibility for its laws in such a manner.

That strikes me as a rather important consideration for the enforcement mechanism in question.

Justice Breyer notes in his dissent (as joined by Sotomayor and Kagan):

I recognize that Texas’s law delegates the State’s power to prevent abortions not to one person (such as a district attorney) or to a few persons (such as a group of government officials or private citizens) but to any person. But I do not see why that fact should make a critical legal difference. That delegation still threatens to invade a constitutional right, and the coming into effect of that delegation still threatens imminent harm. Normally, where a legal right is “‘invaded,'” the law provides “‘a legal remedy by suit or action at law.'” Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 163 (1803) (quoting 3 W. Blackstone Commentaries *23).

Justice Sotomayor (as joined by Breyer and Kagan) was quite direct:

The Court’s order is stunning. Presented with an application to enjoin a flagrantly unconstitutional law engineered to prohibit women from exercising their constitutional rights and evade judicial scrutiny, a majority of Justices have opted to bury their heads in the sand.

After citing appropriate case law she notes:

The Texas Legislature was well aware of this binding precedent. To circumvent it, the Legislature took the extraordinary step of enlisting private citizens to do what the State could not.

[…]

Today, the Court finally tells the Nation that it declined to act because, in short, the State’s gambit worked. The

structure of the State’s scheme, the Court reasons, raises “complex and novel antecedent procedural questions” that counsel against granting the application, ante, at 1, just as the State intended. This is untenable. It cannot be the case that a State can evade federal judicial scrutiny by outsourcing the enforcement of unconstitutional laws to its citizenry.

Emphasis mine.

Justice Kagan also dissented (as joined by Sotomayor and Breyer):

The Court thus rewards Texas’s scheme to insulate its law from judicial review by deputizing private parties to carry out unconstitutional restrictions on the State’s behalf.

The ruling and the dissents are all here for anyone wishing to further review them.

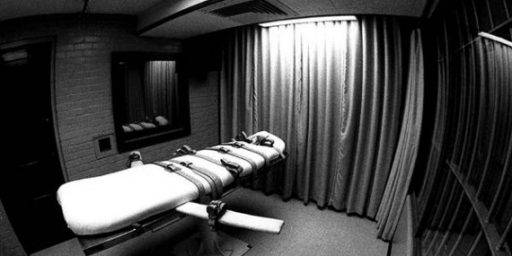

So say we have a woman who is dying and pregnant, early in pregnancy, and we terminate the pregnancy since we think it will improve her chances of survival. I get sued. If I lose the suit, what is the penalty? I thought that I read that the state would provide a bounty of at least $10,000 but what would I face?

Steve

Using special technology, we replay the decision from inside Justice Roberts’s head:

@steve: first, you Pay, not the state. And how much? 10,000 plus Unknown plus your litigating assailant’s lawyer fees. Plus measures to ensure that you can’t do such a thing again, such as closing down your clinic.

@steve: I am a little confused by how your question is worded, but the state does not pay the 10K. If you funded an abortion after 6 weeks and were sued and the court found against you, you would have to pay the 10K and the attorney’s fees to the person who sued you.

Thanks, Was reading some analysis last night while on call and it seemed to describe the $10,000 as a bounty from the state. This makes more sense.

I assume that the state will enforce it so into really sure how you get around the fact that it is really state enforced.

Steve

Technicality, but this was not a ruling. It was an opinion relating to order denying an application for pretrial injunctive relief. The court was not ruling on the merits of the scenario; it was simply refusing to inject itself into the trial process that will be played out in the lower courts. I realize that in a practical sense it’s somewhat immaterial, since the damage will likely be done by the time this issue actually gets before them on certiorari, but it’s not really a ruling.

@HarvardLaw92: That’s a fair point.

@HarvardLaw92:

Although this will not help the real women and real defendants impacted by this outrageous strategy, I hold some feint hope that allowing the actual chaos likely to be unleashed by this statute will be far more instructive in the long run than discussing the theoretical chaos likely to be unleashed. I see this process as a total train wreck for the Texas judicial system. And, I guess we will get to see that.

@Joe:

I agree. As you said though, the unfortunate collateral damage will be the people who have to suffer through the fallout in the meantime. There really should be consequences for the people who caused all of that – but of course there won’t be. There never are.