The Military Has A Suicide Problem

Suicide has become a bigger threat to members of the military and veterans than combat. That needs to change.

In a column at The New York Times, Carol Giacomo notes that suicide has become a bigger threat to members of the military than combat:

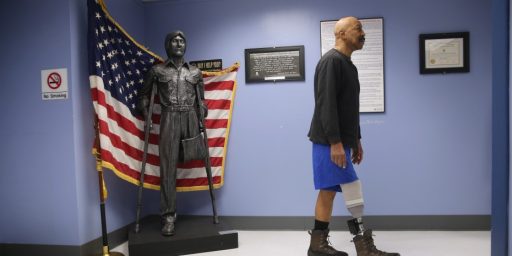

Suicide rates for active-duty service members and veterans are rising, in part, experts say, because a culture of toughness and self-sufficiency may discourage service members in distress from getting the assistance they need. In some cases, the military services discharge those who seek help, an even worse outcome.

More than 45,000 veterans and active-duty service members have killed themselves in the past six years. That is more than 20 deaths a day — in other words, more suicides each year than the total American military deaths in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The latest Pentagon figures show the suicide rate for active-duty troops across all service branches rose by over a third in five years, to 24.8 per 100,000 active-duty members in 2018. Those most at risk have been enlisted men under 30.

The data for veterans is also alarming. In 2016, veterans were one and a half times more likely to kill themselves than people who hadn’t served in the military, according to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform. Among those ages 18 to 34, the rate went up nearly 80 percent from 2005 to 2016. The risk nearly doubles in the first year after a veteran leaves active duty, experts say.

The Pentagon this year also reported on military families, estimating that in 2017 there were 186 suicide deaths among military spouses and dependents.

Military officials note that the suicide rates for service members and veterans are comparable to the general population after adjusting for the military’s demographics — predominantly young and male. But given the military’s size and influence, it is an institution that is well placed to lead the nation in suicide prevention.

Other than pointing to national trends, officials have offered few explanations for why military suicides are rising. Studies seeking more answers are underway.

Experts say suicides are complex, resulting from many factors, notably impulsive decisions with little warning. Pentagon officials say a majority of service members who die by suicide do not have mental illness. While combat is undoubtedly high stress, there are conflicting views on whether deployments increase risk.

Where there seems to be consensus is that high-quality health care and keeping weapons out of the hands of people in distress can make a positive difference.

Studies show that the Department of Veterans Affairs provides high-quality care, and its Veterans Crisis Line “surpasses most crisis lines” operating today, according to Terri Tanielian, a researcher with the RAND Corporation. (The Veterans Crisis Line is staffed 24/7 at 800-273-8255, press 1. Services also are available online or by texting 838255.)

But Veterans Affairs often can’t accommodate all those needing help, resulting in patients being sent to community-based mental health professionals who lack the training to deal with service members.

The rate of suicide for active-duty service members and veterans isn’t that far removed from those for the general population, and the recent increases appear at least in part to the increases that we have seen in suicide among the population as a whole. A study by the Centers for Disease Control, for example, found the following:

- rom 1999 through 2017, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 33% from 10.5 to 14.0 per 100,000.

- Suicide rates were significantly higher in 2017 compared with 1999 among females aged 10-14 (1.7 and 0.5, respectively), 15-24 (5.8 and 3.0), 25-44 (7.8 and 5.5), 45-64 (9.7 and 6.0), and 65-74 (6.2 and 4.1).

- Suicide rates were significantly higher in 2017 compared with 1999 among males aged 10-14 (3.3 and 1.9, respectively), 15-24 (22.7 and 16.8), 25-44 (27.5 and 21.6), 45-64 (30.1 and 20.8) and 65-74 (26.2 and 24.7).

- In 2017, the age-adjusted suicide rate for the most rural (noncore) counties was 1.8 times the rate for the most urban (large central metro) counties (20.0 and 11.1 per 100,000, respectively).

- From 1999 through 2017, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 33% from 10.5 per 100,000 standard population to 14.0 (Figure 1). The rate increased on average by about 1% per year from 1999 through 2006 and by 2% per year from 2006 through 2017.

- For males, the rate increased 26% from 17.8 in 1999 to 22.4 in 2017. The rate did not significantly change from 1999 to 2006, then increased on average by about 2% per year from 2006 through 2017.

- For females, the rate increased 53% from 4.0 in 1999 to 6.1 in 2017. The rate increased on average by 2% per year from 1999 through 2007 and by 3% per year from 2007 through 2017.

In addition, the study found the following:

During this period (1999-2017), the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 33% from 10.5 per 100,000 in 1999 to 14.0 in 2017. The average annual percentage increase in rates accelerated from approximately 1% per year from 1999 through 2006 to 2% per year from 2006 through 2017. The age-adjusted rate of suicide among females increased from 4.0 per 100,000 in 1999 to 6.1 in 2017, while the rate for males increased from 17.8 to 22.4. Compared with rates in 1999, suicide rates in 2017 were higher for males and females in all age groups from 10 to 74 years. The differences in age-adjusted suicide rates between the most rural (noncore) and most urban (large central metro) counties was greater in 2017 than in 1999. In 1999, the age-adjusted suicide rate for the most rural counties (13.1 per 100,000) was 1.4 times the rate for the most urban counties (9.6), while in 2017, the age-adjusted suicide rate for the most rural counties (20.0) was 1.8 times the rate for the most urban counties (11.1). The age-adjusted suicide rate for the most urban counties in 2017 (11.1 per 100,000) was 16% higher than the rate in 1999 (9.6), while the rate for the most rural counties in 2017 (20.0) was 53% higher than the rate in 1999 (13.1).

In other words, suicide is a problem in both the civilian and military worlds. The fact that the suicide rate for the population as a whole has risen so significantly since the start of the 21st Century is, at least in part, one of the reasons why we’re seeing similar increases for a specific segment of the population such as active-duty military and veterans. However, it’s also likely that there are reasons for this phenomenon that are specific to the military. One of the most obvious reasons that many people point to are issues such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other mental health issues that impact soldiers who have served in any of the numerous theaters where the United States has soldiers in the middle of active combat. While the Veterans Administration and other government agencies are supposed to be devoted to the health of active-duty soldiers and combat veterans, the reality is that far too many people have been allowed to fall through the cracks. At the very least, we owe these men and women who have fought for their country the care they need, even in cases where we now oppose the war that they were fighting. Anything less is dishonorable and shameful.

Giacomo closes here column with this, and I think it’s appropriate to post it here:

[T]he crisis line for veterans is 1-800-273-8255 (press 1). Another resource for those having thoughts of suicide is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). You can find a list of additional resources at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

And if you know someone, whether active-duty, veteran, or civilian who appears to need help, reach out to them.

I suspect it’s because we’ve been feeding our military into an incessant meat-grinder with absolutely no plans on how to reach a conclusion. We’ve been fighting in Afghanistan for longer than the entire period of bloody WWII.

And what’s worse is that our politicians don’t seem to care about it. We’ve taken eternal war and its effects on our military as a price we’re willing to pay to keep the neocons and the chickenhawks happy (as well as the media who love to support them.) After all, it’s not THEIR children who are getting blown up with IEDs or having to live in a war zone, is it?

I suspect our soldiers can’t help but know unconsciously that they’re being used as sacrificial fodder and aren’t really cared about. They’re pulled mainly from lower-middle and lower-class households, often dysfunctional, where volunteering for the military is one of the very few paths teenagers can see to get their lives together in an environment littered with McJobs and oxycontin. We cheer and wave flags and say “we thank you for your service!” but we’re not doing what would really, really show we cared about them: getting. them. out. of. wars. and stop USING them.

I’ll freely admit that I’m out of my depth when it comes to the issues that lead to suicide among military personnel, but I wonder as @grumpy realist: suggests that incessant and continuing deployments of the same troops isn’t a major part of the problem. And that the move to a professional military with an all volunteer military is part of the problem. Perhaps we are better off returning to the draft for a number of reasons.

Though I do remember suicide and social adjustment issues among Viet Nam vets who were by and large draftees.

Sebastian Junger has a theory that it’s less about PTSD and more about the loss of comradeship, membership in a platoon. IIRC his example involves a sergeant who does three deployments where he’s in a tight community, part of a mission-oriented team. . . and suddenly he’s wearing an orange apron at Home Depot. So less PTSD or too much fighting, more the sudden emptiness and loss of meaning of a dead end job. I don’t know if that holds up but it’s an interesting take.

I believe a lot of teen suicide is related to that theory in that the kids are often people who’ve been shunned, excluded from a group. Then there are the old guys who are retired and similarly have lost their anchoring group. One can see a through-line there. If your identity is group-focused and you lose the group you lose identity.

@Michael Reynolds: That would be consistent with the doubling of suicide risk in the year after discharge, but roughly tracking with the suicide rates of the age-and-gender-adjusted population otherwise.

My guess is that the sudden lack of structure is more of a problem than the unbearable pointlessness of directing people to the right aisle at Home Depot. I suspect there are a lot of military tasks just as unfulfilling.

@Michael Reynolds:

That matches a lot of what I have heard from friends who work with combat veteran re-entering the community.

I believe there is also evidence about how that also fuels the military to law enforcement pipeline (which in turn had led to the increasing militarization of policing). My thoughts on that pipeline (which I am definitely still developing) are complex, but overall I don’t think it’s a good thing. That said I also think it’s easy to understand why it’s happening.

@grumpy realist: The numbers don’t bear this out. Military and ex-military suicide rates are roughly in line with civilian rates.

There’s lots of things that seem obvious to the layperson that don’t match the data.

I’m surprised that a self-selected group (we have a volunteer military) who go through a significant mental reprogramming (not necessarily a bad reprogramming), who live in a very artificial structure for years — that these people then come out and kill themselves at the same rates as the rest of the population, and that both groups have those suicide rates change at the same time. I think that’s wacky.

@grumpy realist: As I’ve mentioned before, there are a few old crusties around from the heavy deployment days of 03-09….but not many. They’ve retired or separated and moved into the civilian sector. Over the past 10 years the majority of troops doing deployments have been spec ops forces. It’s become increasingly rare to find regular military personnel with any sand in their boots. Yet, these are the kids committing suicide. Dont get me wrong, garrison military life is still stressful–especially when trying to realize the nation’s mandate to be ready for war–in a climate when every service is at deplorable readiness levels. The kids have to train to be good at their jobs, and comply with unit additional duties on top of all the additional training for sexual assault, human trafficking, suicide prevention, cyber security, anti-terrorism, etc. Its alot to be responsible for and I suspect that culturally, today’s generation finds checking out to be an acceptable response to anxiety and depression. The human experience has always been stressful…but previous generations of people placed a premium on courage, toughness, and resilience. Those aren’t defining values to 35 and unders. This is a result of the larger culture and what we chose to amplify and revere. I remember when the family left behind was looked at as the victim. Now the victim is the person committing suicide.

This is not an issue that more training and awareness can fix.

I looked at suicide rates by state, and it turns out that rates were high in Western states like Wyoming, Montana, and Alaska and low in New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts. In New York state, rates were low in urban downstate counties and higher in upstate rural counties. I have no sensible theories, but I wonder if a high proportion of military recruits might not come from western, rural hotshots for suicide.

There have been suicides in my immediate family. The issue remains beyond my comprehension.

@Slugger:

I’ve read that the higher suicide rates in rural areas, whether up state NY or Wyoming can be attributed to 3 things; economic opportunity, lack of mental health resources in the community and the prevalence of guns.

When I worked in mental health and went through suicide prevention training, one of the factors in determine the risk of a person suiciding was the lethality of their proposed method.

@Slugger:

It may track access to guns.

“…that these people then come out and kill themselves at the same rates as the rest of the population, and that both groups have those suicide rates change at the same time.”

That would seem to indicate that the two populations have a shared triggering factor. Interesting problem. What’s going on currently that causes a specific cohort/age group to commit suicide more frequently than in the past?

Lack of mental health resources, negative societal responses to people who seek out mental health treatment (Oh, suck it up and don’t be a pussy!), access to weapons and/or lethal amounts of drugs/alcohol, most often in combination…..we’ve had many local citizens in this sparsely populated county commit suicide in the last 3 years, and none of them were sober when they killed themselves.

@Slugger:

Uniformed military personnel are recruited disproportionately from the South and the West, including Alaska and Hawaii. The lowest accession rates are from the urban Northeast and the industrial upper midwest.

I do not believe it matters where a person is from or what part of the country they are from. The active military suicide epidemic that is happening, are happening stateside. A lot of them have not been deployed, have never left their commands. My son, Brandon Caserta died by suicide June 25, 2018 by jumping into the rotating rear tail rotor of a helicopter on his command’s flight line, twice. He left 6 letters stating why he did what he did and it was due to the toxic abusive leadership in his command, HSC-28 (Helicopter Sea Combat 28). He was exactly 21 years and one month old to the day. He went to his command and told them he was depressed; everyone knew he was depressed and all they told him was “You are fine so get back to work” or they would go tell him to make himself useful somewhere else. Not one person in that command helped him or cared about his well being. In everyone’s statement, they stated they knew he was depressed but never thought he would do what he did. Please read his entire story at https://militarycorruption.com/brandon-caserta/. Everything in it is factual due to Brandon documenting EVERYTHING on his phone and computer. There is quite a bit missing because I didn’t want to disclose everything we had, just in case we need it. Leadership needs to be held accountable for suicides that happen especially if the leadership is the issue. We have had so many people contact us due to their toxic and abusive leadership and we have saved many lives this past year. We are quite busy making sure the ones who reach out to us are taken care of and we show them how to get help without retaliation. Retaliation is the ONLY reason why these people are afraid to get the help they need.