The Supreme Court Is The Most Agreeable Place In Washington

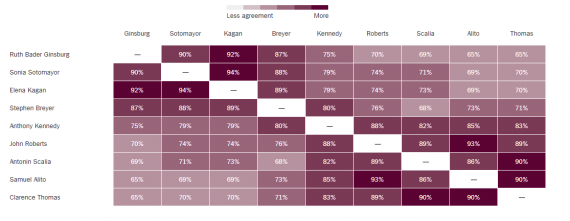

Even the most ideologically divided members of the Supreme Court agree with each other 65% of the time.

The New York Times’ Upshot blog did an interesting examination of recent Supreme Court opinions and found much more consensus among the nine Justices than currently exists in Washington:

The Supreme Court has entered the final days of the term, when the court typically announces its most hotly debated and consequential decisions. Those rulings can overshadow broader trends. The nine justices will soon complete their fourth term together, and their thousands of votes in 269 signed decisions in argued cases in those years show some clear and sometimes surprising patterns.

The justices are one of the lasting legacies of the presidents who appoint them, and you might expect ones appointed by the same president to vote together particularly often. This is certainly true of the four newest justices. The ones appointed by President Obama, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, have agreed 94 percent of the time. The members of the court appointed by President George W. Bush, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., have agreed 93 percent of the time.

The tendency is less marked among justices on the bench longer. President Bill Clinton’s nominees, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen G. Breyer, were less likely to agree, at 87 percent. And President Ronald Reagan’s appointees, Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony M. Kennedy, have agreed just 82 percent of the time.

In their public appearances, the justices often complain that the press focuses on closely divided cases and not on the many unanimous ones. The court is indeed often united, and it will end this term with unanimous decisions in more than half of its cases. Over the past four terms, even the members of the court least likely to agree voted together 65 percent of the time.

This rough consensus has been on display quite prominently in the last week or so as the Supreme Court has handed down decisions in what are mostly its less prominent cases on issues ranging from software patents to bankruptcy law. While there have been a couple cases where there has been more than one opinion issued, usually indicating that the Justices disagree about the reasoning that should lead to a particular result, each of these cases has been unanimous in the result. Since these cases don’t get nearly the amount of press attention that the high-profile cases that are likely to be handed down in the next several days will, people don’t notice the fact that there’s a lot more agreement than disagreement on the nation’s highest court. Indeed, as this chart shows, even the starkest level of disagreement — between Justice Thomas and Justice Ginsburg — means only that those two Justices are on the opposite side of cases in just 35% of the cases that the Court decides: (click to enlarge)

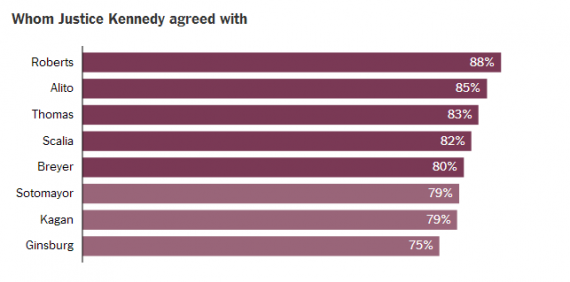

The Justice of most interest, of course, is Anthony Kennedy, who is largely seen as being at the center of the Court at this point and has been the deciding vote in a host of cases, especially since Justice Sandra Day O’Connor retired. Not surprisingly, Kennedy has some of the highest rates of agreement with his fellow Justices, with a slight tilt toward the more conservative side of the Court:

Given the fact that it’s hard to find consensus like this among liberal and conservative members of Congress, I suppose this is surprising but I think the finding that the Court is a remarkably “agreeable” institution can be explained by the nature of the institution and the work that it does. Off the top, it is quite obviously easier to find agreement among nine people from largely similar backgrounds — all of the Justices graduated from an Ivy League Law School and all but three of them (Thomas, Ginsburg, and Breyer) went to Ivy League schools at the undergraduate and graduate levels, for example — than it is to find agreement among 435 members of the House or 100 members of the Senate. Indeed, because the Court requires majorities to agree on at least the outcome of a case, Justices are essentially compelled to find agreement with their co-workers in order to get their work done. Most of the Justices, indeed all of them except for Justice Kagan, learned this lesson about building consensus during the years that they spent on the Courts of Appeal prior to being named to the nation’s highest court. Finally, because of the nature of the issues that the Justices deal with and how the law “works,” it is simply much easier to find consensus among even people who are ideologically diverse than it is when dealing with the issues that come before a legislature. In that sense, I don’t think it’s fair to say that there are any “lessons” that politicians can learn from the Supreme Court, because they serve such different functions in very different environments, Justices and Congressman or Senators quite simply approach issues from such completely different angles that there’s no point in comparing the two.

Over the next few days, and possibly by the end of the week depending on how many opinions are handed down on Wednesday and Thursday, the Court will hand down the final opinions of the October 2013 Term. Since these are the “high profile” cases of the term there are likely to be sharp ideological divisions between the Justices. For the most part, though, it’s worth noting that these nine men and women agree with each other much more than they disagree, it’s just that we’re only really paying attention when the disagreements are likely to be on display.

Interesting. I wonder how much of that is a function of time on the Court.

Oh my god, in agreement only 87% and 82% of the time?

Seriously though, I suspect that the level of agreement is very high – between and among various combinations of justices – because most of the cases are relatively pedestrian and do not lead strongly partisan ideological opinions.

@al-Ameda:

Not that I really disagree with most not being strongly partisan, but I thought pedestrian cases never even make it to the SC … I was always under the impression that they only heard cases which aren’t legally obvious.

One of the most telling anecdotes about the Court is that Scalia and Bader-Ginsburg are really good friends despite being on opposite ends of the political spectrum. I’ve seen them interviewed about it and they both basically say that they think the other person is wrong on some things, but that doesn’t diminish their mutual respect and friendship. It seems to me we used to have a lot more of that in Washington.

If you ask me, the biggest reason there is so much agreement on the court, however, is that 1) they aren’t running for election, so don’t have to pander to anyone; 2) they don’t do the TV talking heads.

@george:

I understand your point, however not all cases push the ideological hot-buttons like ACA, extending voting rights, Citizens United, and so forth.

That’s what I intended to say, I apologize for the lack of clarity.