Donald Trump Wants A Line Item Veto. He’ll Need A Constitutional Amendment.

Like many Presidents before him, Donald Trump wants a line-item veto. Getting there won't be easy, nor should it be.

During the press appearance on Friday during which he berated Congress for passing a 2,000+ page omnibus spending bill to keep the government funded through the end of the Fiscal Year in September, which he had threatened to veto just hours after it had finally passed the Senate early Friday morning, President Trump repeated a request that President’s have been making for the better part of the past 140 years or so:

President Donald Trump on Friday called for reinstating the line-item veto, a practice ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1998.

Trump’s call for a line-item veto, by which he would be able to reject specific portions of a measure without vetoing a piece of legislation entirely, came amid afternoon remarks at the White House Friday in which he excoriated Congress, especially Democrats, for sending him an omnibus bill that met his demand for a dramatic increase in military spending but nonetheless included funding for “things that are really a wasted sum of money.”

“To prevent the omnibus situation from ever happening again, I’m calling on Congress to give me a line-item veto for all government spending bills, and the Senate must end — they must end the filibuster rule and get down to work,” the president said. “We have to get a lot of great legislation approved, and without the filibuster rule, it’ll happen just like magic.”

Trump said he had signed the omnibus bill, which he had threatened earlier Friday to veto, but declared he would never again sign such a bill, which, he complained, contained too much spending and had been presented to him with insufficient time to read its 2,200-plus pages

The line-item veto is, of course, basically the authority of a Chief Executive to veto certain provisions of a spending bill without having to veto the entire bill. Forty-three states have some form of the line-veto power reserved to their Governors, with only Indiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Vermont being the only states that do not grant their Governors such a power. Some cities also give a similar power to their Mayor. The line-item veto was also granted by the Constitution of Confederate States of America, although there’s no indication that Jefferson Davis ever exercised that power during the four years that nation actually existed. In the case of the Federal Government, pretty much every President from Ulysses S. Grant through to today has asked for a similar power. Not surprisingly, Congressional efforts to grant that power, either via Constitutional Amendment or legislation, did not get very far since Congress has generally been reluctant to hand over such power to the Executive Branch.

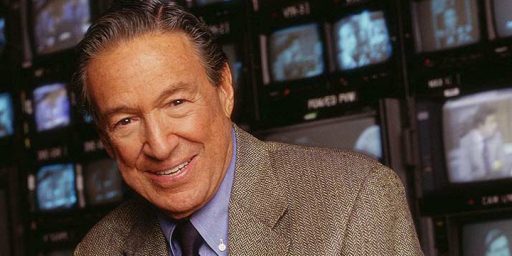

That changed, ironically enough, during the Presidency of Bill Clinton in the wake of the 1994 midterm elections that saw Republicans take control of both the House and the Senate for the first time in a half-century. In 1996, Congress passed the Line Item Veto Act of 1996 with overwhelming margins in both bodies. The bill purported to give the President the power to veto individual items in a spending bill and provided for a procedure whereby Congress could override that veto, which is also basically how the procedure works at the state level. In any case, the law was subjected to immediate court challenges, One such lawsuit, filed by a group of U.S. Senators, resulted in a ruling by Judge Harry Jackson of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia that the law was unconstitutional. That case, though, was appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, which accepted the case and ruled that the Senators lacked standing to challenge the law because they could not demonstrate that they individually had suffered the kind of particularized harm necessary to have the standing to sue in a Federal Court required under the Constitution. As a result, the underlying ruling finding the line-item veto unconstitutional was nullified. This meant that the line-item veto was allowed to stand, although it didn’t take long for new legal challenges to pop up.

Not long after the Supreme Court’s decision, President Clinton used the line-item veto to veto one spending item in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and two provisions in the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. In response to these moves, several challenges were filed by entities impacted by the line item veto, including the City of New York, several hospital associations, and a farmer’s cooperative. These challenges were ultimately combined in a case that came to be known as Clinton v. New York and resulted in a ruling by Judge Thomas Hogan of the District Court for the District of Columbia that the law was unconstitutional. As with the Raines v. Byrd case noted above, this case was appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. This case, of course, did not suffer from the standing case that the previous case had so it led to a decision on the merits by the Supreme Court, which decided by a 6-3 majority that the Line Item Veto Act was unconstitutional. In its ruling, the Supreme Court relied on the Presentment Clause of the Constitution, which lays out the procedure by which laws are supposed to be enacted under the Constitution. Essentially, the Court ruled that the Line Item Veto Act was unconstitutional because the Constitution was silent on the issue, which the majority held to be equivalent to “an express prohibition” and agreeing with those arguments that concluded that statutes can only be enacted “in accord with a single, finely wrought, and exhaustively considered, procedure.” As a result, the Court ruled, a bill can only be approved or rejected by President in its entirety as provided in the Constitution.

Subsequent to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Clinton v. New York there have been several legislative efforts in Congress to attempt to find a way around the Court’s ruling, including one during the early years of President George W. Bush’s second term and another during President Obama’s first term. The Bush-era proposal never made it to a final vote in either the House or the Senate, and the proposal put forward during the Obama Era died in the Senate after passing the Republican-controlled House. Since then, the general consensus has been that the only way to give the President a line-item veto would be via a Constitutional Amendment that would address the issues raised by the court in its 1998 ruling. To date, there’s been no serious effort to push such an amendment through Congress and no indication that it would have sufficient support in either the House and the Senate to be presented to the states for ratification.

Notwithstanding all of this, the President’s Secretary of the Treasury seems to think that Congress could simply grant line-item veto authority to the President:

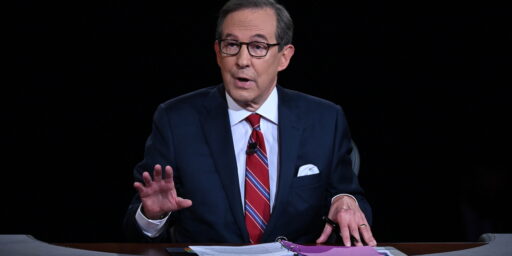

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has urged lawmakers to give President Trump a line-item veto, saying on “Fox News Sunday” that it might prevent Democrats from stacking more nondefense discretionary spending into the next must-past budget bill.

But Mnuchin’s short exchange with Fox News anchor Chris Wallace also underlined the problem with the idea — a 20-year-old Supreme Court ruling that struck down the line-item veto, finding “no provision in the Constitution that authorizes the president to enact, to amend or to repeal statutes,” after President Bill Clinton used it 82 times.

“I think they should give the president a line-item veto,” said Mnuchin, echoing Trump’s comments after he signed last week’s omnibus budget bill.

“That’s been ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court,” Wallace said.

“Well, again, Congress could pass a rule, okay, that allows them to do it,” Mnuchin said.

“It would be a constitutional amendment,” Wallace said.

“Chris, we don’t need to get into a debate,” the treasury secretary said. “There’s different ways of doing this.”

Here’s the video of Mnuchin’s interchange with Wallace:

This was a bizarrely painful and embarrassing exchange between Secretary Mnuchin and Fox News Sunday’s Chris Wallace. It’s what happens Trump picks wealthy, well-connected people to run our country. They believe they can do *anything*. pic.twitter.com/SVZyA5XUJ4

— Nancy Pelosi (@TeamPelosi) March 25, 2018

Mnuchin, of course, has no idea what he’s talking about. While there may be some valid policy reasons for granting a line-item veto to the President, it’s clear that this can only be done via a Constitutional amendment. It’s a hard process to get such an amendment ratified, but as I’ve said before, that’s a good thing. It should not be easy to make radical changes to the way the Federal Government operates and the balance of power between the Legislative and Executive Branches such as the one the line-item veto represents.

Steven Mnuchin, one of the “best people” trump hires.

Why does a “master negotiator” need the ability to veto single items in an already agreed-upon document? Shouldn’t he have been able to get his way before it got to that stage?

Furthermore, why in the world would *anyone* in Congress agree to any kind of compromise if they knew it could be wiped out with a stroke of POTUS’s pen and they just got played like a sucker? We compromise specifically because it’s all or nothing for bills to pass. All a line-item veto would do is mean the dominate party gets their way all the time and the minority party gets screwed without lube.

@KM:

Trump has failed to negotiate an item of importance in his 14 months.

He said he would sign off on a bipartisan immigration deal, then at the table he pulled that ‘sh**hole nations’ stunt. I suppose he figured that Democrats would cave in, return to the table with a proposal to fund his Vanity Wall in exchange for a limited DACA extension.

Is Mnuchin really this stupid? Or are bankers on his level simply so arrogant that they assume even the constitution is for other people? Whether or not you can change the constitution by statute or by sheer force of will is not a “debate” — unless you have contempt for everything except your own perceived power.

The implication is that since normal rules don’t apply to team Trump, the Constitution and the law shouldn’t apply either.

“which, he complained, contained too much spending and had been presented to him with insufficient time to read its 2,200-plus pages”

Yeah, like he readsstuff…riiiiight.

@Just ‘nutha …:

Insufficient time for his staff to read it and translate it into one-syllable words he might understand.

But most important, also insufficient time for the all-important Department of Fox & Friends to review it.

Of course, the Supreme Court could also change its mind about the meaning of the presentment clause, just as it has on other occasions regarding other constitutional provisions; there’s been substantial membership turnover since the Clinton v. New York decision, so it wouldn’t even require anyone to change positions on the case. A reinterpretation of the power of Congress to rein in both executive spending and failure to spend appropriated funds by the Anti-Deficiency Act could also have similar effects to the line-item veto, regarding budgetary decisions at least.