On Democratic Responsiveness

A lesson from Puerto Rico and further reasons why the EC is a problem.

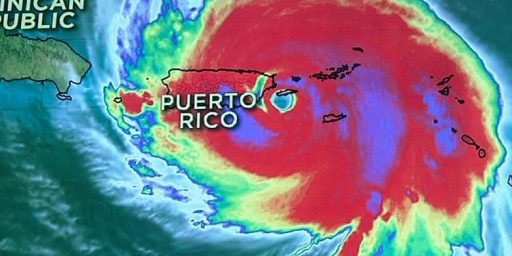

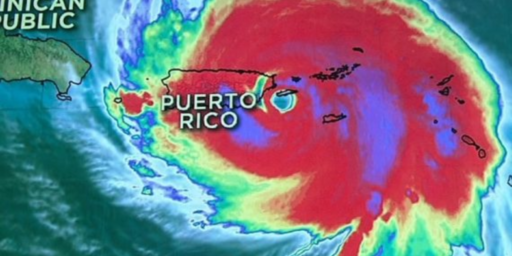

Earlier this week I noted the fact that the sitting President of the United States was rather publicly scolding the citizens of Puerto Rico over the island’s clear need for federal aid in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. I noted my agreement with Susan Hennessey that Trump’s response was a glaring example of why the residents of Puerto Rico ought to have a vote for president. (That which follows fits, at least to a degree, on my ongoing series on Democracy and Institutional Design–the most recent part, Part III, was posted here).

A fundamental notion of representative democracy is that power-seeking politicians have to appeal to large numbers of citizens to obtain said power and, moreover, that they are held accountable once in office by the fact that to be re-elected (i.e., retain power) they have to continually convince a critical mass of citizens to keep voting for them. Good performance should beget votes and bad performance should beget being voted out of office.*

So, in simple terms, a politician is elected in a competitive process, making certain representations as to how they will govern. Once in office they are afforded the chance to perform more-or-less as promised as well as facing problems and issues (like natural disasters) that require governmental response. Then, at regular intervals, the voters get to decide is the politicians remains in power or goes (indeed, this basic feedback function is why I am not a proponent of terms limits).

So, when I referred to a “significant democratic deficiencies in our constitutional order” in my post about Trump’s declarations about Puerto Rico, this is exactly what I am talking about. Trump has zero to fear from the citizens of the island. They have zero influence over his re-election and, worse, they have no other real mechanisms to influence his behavior. There is no pressure from Puerto Rican members of Congress, because there aren’t any. Trump might as well treat PR like it isn’t part of the US because from his highly transactional view of politics, they don’t matter.

Indeed, it is worth noting that good institutional design that forces politicians to be responsive are more important when dealing with a politician like Trump who sees the world in terms of what is in it for him, as opposed to for some broader sense of public service. He doesn’t do compassion. He doesn’t do duty. He doesn’t see himself as President of the United States. He sees himself as President of his base.

When my state of residence, Alabama, was hit by some devastating storms recently, Trump (who is quite popular here, and he knows it) tweeted the following:

After all, not only did Alabama vote in droves for Trump, he can always come down and hold a rally and find adoring fans. Gotta show love to the fans!

However, when California was facing a catastrophic fire season, he tweeted the following:

So, if you are in a state that Trump likes and needs, it is time for “A Plus treatment.” If you are from a state that Trump has no shot of winning, and therefore is of no use, he threatens to withdraw funds. And if you are from a portion of the country with zero leverage, you get treated like you aren’t even part of the USA.

At least California has two Senators and fifty three members of the House, seven of whom are Republicans (including the House Minority Leader, Kevin McCarthy),** to combat any attempt to remove aid to the state. Puerto Rico has one Resident Commissioner who has voice, but no vote. The only reasons for Trump to listen to PR is either duty or compassion. He shirks his duty and he seems to only have compassion for those who like him (which really isn’t compassion).

The Electoral College exacerbates this kind of situation. Trump has no reason to care about voters in California, because none of them can help him. The roughly 4.5 million Californians who voted for Trump don’t matter, not even to Trump. They are irrelevant to his cause. They cannot help him win reelection in 2020, so better to heap scorn on the state as nothing more than 55 electoral votes he has no hope of winning.

The system we use to elect the one office that theoretically represents the whole country incentivizes a solipsistic politician to ignore, if not actively attack, the most populated state in the union. That is a fundamentally anti-democratic incentive.

For a representative democracy to function, there has to be an operative feedback loop. For the people of Puerto Rico, there is no such mechanism as it applies to the federal government. Indeed, as I noted in the post that inspired this one, roughly 4 million Americans across several territories lack basic representation in the federal government. They are ignored (indeed, save in times of disaster, we rarely think about them). Most of those citizens are in Puerto Rico (3,195,153), but also Guam (165,718), the US Virgin Islands (104,914), American Samoa (55,641), and the Northern Mariana Islands (55,194). And, of course, the District of Colombia (702,455) which at least has 3 electoral votes, but lacks real congressional representation.***

So these are all forgotten citizens without voice. The lack of attention to Puerto Rico in the face of true devastation simply proves the point. Had similar damage happened to Mississippi (a state with a smaller population than PR), Trump would not be tweeting about how the locals should stop whining about the situation.

I recognize that PR also gets short shrift because it is an island and that the fact that its population is both Hispanic and Spanish-speaking creates, a distance in the minds of many (that situation is problematic in its own way, but I will leave the ethno-racial discussion out this analysis). But I still circle back to the fact that Trump would have more reason to care if there were voters (and members of Congress) from the island that he would have to answer to.

But, again, given the EC (and the high probability PR would vote Democratic), he would still feel fully empowered to ignore the place.

I realize that I am trying to weave a couple of different points together in this piece, and not as elegantly as I might like. So, let me try and tie this all together: Puerto Rico is a singular example of a large cluster of Americans who really have no influence over the national government, and this is especially true with a politician like Trump in the White House. We can add hundreds of thousands of other Americans who are likewise disenfranchised in terms of national office across several territories. This walling off of citizens into boxes sans voice and influence has some connectivity to the way voters are walled off by the Electoral College. Republicans in California don’t matter, ergo California doesn’t matter to Trump. All of these observations are linked to institutional design–indeed, to poor institutional design. They certainly illustrate the degree to which the designers of our constitutional order simply whiffed on questions linked to basic democratic accountability.

I know people romanticize the Framers and the constitution. I accept that there is a powerful small-“c” impulse in our political culture (we don’t like change, especially of the Constitution, which we rationalize as being far more impressive and efficacious than it is). I certainly recognize how hard change is. Still, I will persist is trying to point out these deficiencies in the hope that it spurs some thought about whether they are worth the costs they impose, as well as to aspire to inspiring further conversation on these topics.

We should all want politicians who are responsive to citizens, which is why all citizens need to be voters and why all votes ought to be of equal value.

_______________________________

*And by “good” and “bad” I do not mean some objective standard of goodness, but rather the collective perceptions of the electorate.

**BTW, while CA is heavily Democratic (it voted 62% for Clinton and only 31% for Trump, and roughly 60-40 in the last governor’s race) the ratio of D:R in the House delegation (46:7) means that D’s are over-represented. This is just another example of how our system for electing the House is problematic from a representation POV.

***As noted, PR has a Resident Commissioner, and DC, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the US Virigins Islands each has a Delegate. All serve on committees and can speak and introduce legislation, but none can vote.

Steven, you have my whole hearted support. But I ask you directly: do you think that a popular vote in 2016 would have solved anything? Short term, Clinton over Trump is a huge win, but medium term? Democracy cannot long stand a highly polarised 50-50 citizenry. Our problems run deeper.

To top it off, everyone seems to agree that the EC cannot be fixed given our current situation. I feel churlish to criticize your obvious level-headed good sense and serious thought on the matter, but where is the way forward?

@Kit: I have come to the conclusion that all I can do is try and induce thought on the subject and hope that the conversation grows. The system is flawed without a doubt–and the first step is try and convince folks this is the case.

In regards to 2016: it is less that I think HRC winning would have solved anything as I am pointing out that 2016 is a clear data point in the flaws of the system.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Don’t apologize. Be loud and proud.

If you’ve reached the point where can no longer just describe, but feel the need to advocate for better structures, then just do it.

Part of me wants to say that this is unprecedented, and a sign of the unique horribleness of Donald J. Trump, but then I remember the Republicans in Congress who were initially balking at aid for Hurricane Sandy because it hit the Northeast. It’s a moment where America changed — one party stopped caring about America. Trump’s FEMA policies and priorities are an extension of this, as was his tax cuts that were designed to screw over blue states.

Trump didn’t get away with with blowing off California, but he’s pretty much done so with Puerto Rico. And, yes, that’s largely because they aren’t a state and they speak Spanish. But the problem is deeper than that.

The problem is Republicans deciding that half the country is “other”. Democrats often look down on the square states in the flyover country, but it’s more the way one looks down on their idiot brother than by saying we aren’t all Americans.

I don’t know if the people of the square states hate the coastal Americans, or whether the primary system has gotten so out of hand that’s it’s dominated by a tiny sliver of crazy. And I don’t know what we can do about it. I don’t want to sink to that level next time we are in power, to try to teach the square states a lesson,

(I do believe that the George W. Bush administration did their best with Hurricane Katrina, but that their best simply wasn’t good enough)