James Brady’s Death Ruled A Homicide

Could John Hinckley, Jr. face murder charges 30 years after his attempted assassination of President Reagan?

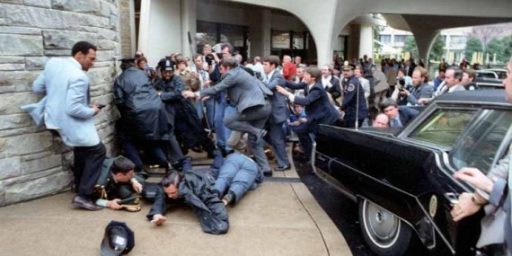

On Monday, more than 33 years after he was shot during the attempted assassination of President Reagan on March 30, 1981, former White House Press Secretary James Brady passed away. Yesterday, a Virginia Medical Examiner classified Brady’s death as a homicide, setting up the possibility that John Hinckley Jr, currently still hospitalized at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, could be charged with his murder:

WASHINGTON — The death this week of James S. Brady, the former White House press secretary, has been ruled a homicide 33 years after he was wounded in an assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan, police department officials here said Friday.

Officials said the ruling was made by the medical examiner in Northern Virginia, where Mr. Brady died Monday at 73. The medical examiner’s office would not comment on the cause and manner of Mr. Brady’s death.

“We did do an autopsy on Mr. Brady, and that autopsy is complete,” a spokeswoman said.

Gail Hoffman, a spokeswoman for the Brady family, said the ruling should really “be no surprise to anybody.”

“Jim had been long suffering severe health consequences since the shooting,” she said, adding that the family had not received official word of the ruling from either the medical examiner’s office or the police.

The ruling could allow prosecutors in Washington, where Reagan and Mr. Brady were shot on March 30, 1981, by John W. Hinckley Jr., to reopen the case and charge Mr. Hinckley with murder. The United States attorney’s office said Friday that it was “reviewing the ruling on the death of Mr. Brady” and had no further comment.

Mr. Hinckley was found not guilty in 1982 by reason of insanity on charges ranging from attempted assassination of the president to possession of an unlicensed pistol. The verdict was met with such outrage that many states and the federal government altered laws to make it harder to use the insanity defense. Mr. Hinckley, now 59, has been a patient at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington since the trial.

There is no statute of limitations on murder charges, but any attempt to retry Mr. Hinckley would be a challenge for prosecutors, in part because he was ruled insane, said Hugh Keefe, a Connecticut defense lawyer who taught trial advocacy at Yale University.

“They’re dead in the water,” Mr. Keefe said. “That’s the end of that case, because we have double jeopardy. He was tried; he was found not guilty based on insanity.”

But George J. Terwilliger III, who was the assistant United States attorney in Washington when he wrote the search warrant for Mr. Hinckley’s hotel room, said there might be grounds for a new trial.

“Generally, a new homicide charge would be adjudicated on its merits without reference to a prior case,” said Mr. Terwilliger, who became a deputy attorney general under the elder President George Bush and is now in private practice. “The real challenge here would be to prove causation for the death.”

Mr. Hinckley’s lawyer, Barry W. Levine, acknowledged new charges were possible, but said the possibility was “far-fetched in the extreme.”

“There’s nothing new here that happened,” he said.

Off the top, it’s worth noting here that the fact that Brady’s death has been ruled a homicide does not necessarily mean that criminal charges will be brought in his death. As a general rule, when any person dies the cause of their death must be noted on the official records that result in the creation of a Death Certificate and, in the end, there are only a limited number of causes of death. That cause of death could be natural causes such as disease, accident, suicide, or homicide, which is broadly defined as “the killing of a human being due to the act or omission of another.” There are many forms of homicide, some of which aren’t necessarily crimes, such as justifiable crimes. In any case, though, in the case of Brady’s death if there is medical evidence that his ultimate cause of death can ultimately tied to the injuries he suffered as a result of the shooting on March 30, 1981, then it was entirely proper for his death to be classified as a homicide. Ultimately, it is as much a statistical classification as anything else, but of course that classification could have legal implications depending on how prosecutors in the District of Columbia choose to act.

Labeling Brady’s death a homicide, of course, has implications far beyond the question of how his death in 2014 will be classified in the statistical records, of course. The question now is whether John Hinckley, Jr, who has been hospitalized at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in the District for three decades since he was found not guilty by reason of insanity, could be charged with his murder thirty-three years after the act which is allegedly the cause of Brady’s death. Given the fact that there is no statute of limitations for murder, the fact that three decades has passed is not a bar to bringing charges itself. However, there are several reasons why any murder charges against Hinckley at this point in time would be legally tenuous and, ultimately, could end up with the same result that his acquittal three decades ago.

The original 13 count indictment against Hinckley in Federal Court, for example, included attempted murder charges under both Federal and District of Columbia law for the shootings of President Reagan, Metropolitan Police Department Officer Thomas Delahanty, Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy, and Brady.(See this article from the Toledo Blade from August 25, 1981, and this Christian Science Monitor article from the same day.) He was acquitted on all of these charges based on the psychiatric evidence that was presented in Court. While double jeopardy would not, in theory, bar bringing murder charges even though Hinckley was a acquitted of the attempted murder of the same person since these are different offenses, one would imagine that Hinckley’s defense would clearly raise this argument before trial.

More importantly, though, even if the prosecution were able to get beyond the double jeopardy issue it is hard to see how they’d be able to avoid the same outcome that they ended up with 32 years ago. While the law has changed significantly since the Hinckley verdict regarding the what a Defendant must prove in order to establish legal insanity at trial, it seems clear that the law that would apply in a trial today for the murder of James Brady would be the law as it existed in 1982 when Hinckley was on trial. Whether Hinckley was tried before a jury or by a Judge, that trier of fact would be required to apply the law as it existed back then, which was much more favorable to Defendants than it is today. Additionally, the evidence that the trier of fact would be required to consider in this regard would be regarding Hinckley’s mental state at the time of the shootings, not his mental state today which is apparently vastly improved according to recent evaluations by the doctor’s treating him. If Hinckley was not guilty by reason of insanity based on that law and that evidence 32 years ago, then it strikes me that there’s no reason to think that he shouldn’t be found not guilty by reason of insanity today if he were to be charged with Brady’s murder.

In addition to the mental health issues, prosecutors could also be faced with evidentiary problems in trying to link the March 1981 shooting with Brady’s death some 401 months later. The Medical Examiner’s determination that Brady’s death is a homicide does not end the legal question of just how one can tie the events of March 1981 to Brady’s death. Typically, one only sees murder charges filed at a late date like this in cases where someone had been in a coma for a long period of time after being assaulted and then died as a result of their injuries. That didn’t happen in Brady’s case. He was shot some three decades ago, and while he did have to deal with those injuries for the next three decades it may be a long shot to try to hold Hinckley legally responsible for his death on Monday.

Eugene Volokh has a comprehensive look at the legal issues involved in a potential murder prosecution against Hinckley, and concludes that it’s unlikely that prosecutors would be able to bring such a case to trial:

The answer is no, likely for two different reasons.

At common law, a murder charge required that “the death transpired within a year and a day after the [injury]” (seeBall v. United States (1891), and this apparently remains the federal rule (see United States v. Chase (4th Cir. 1994)). Many states have apparentlyrejected this rule, given the changes in modern medicine that make it much easier to decide whether an old injury helped cause a death; but though the Supreme Court in Rogers v. Tennessee (2001) held that a court could retroactively reject the rule without violating the Ex Post Facto Clause (which applies only to legislative changes to legal rules) and the Due Process Clause, any such retroactive rejection of the year-and-a-day rule seems unlikely in this case (given that for the rule to be reversed the case would likely need to go up to the Supreme Court, and that in any event the rule had been applied relatively recently, in Chase).

(…)

Under the “collateral estoppel” doctrine (Ashe v. Swenson(1970)), “when an issue of ultimate fact has once been determined by a valid and final judgment, that issue cannot again be litigated between the same parties in any future lawsuit.” That’s most commonly applied in civil cases, but it also applies in criminal cases, against the government (so long as it’s the same government involved in both cases).ltimately, the question of whether or not murder charges are brought will be in the hands of the U.S. Attorney in Washington, and the District’s Attorney General. As things stand right now, though, it seems as though such charges would be on legally tenuous grounds.

The jury determined by a valid and final judgment that Hinckley was insane, and thus couldn’t be liable for attempted murder. This judgment is binding on the government, and since the insanity defense applies the same way for murder as for attempted murder, it means that Hinckley would now be conclusively presumed to have been insane for purposes of any murder prosecution as well. He would have an ironclad defense to the murder charge, and thus any case against him couldn’t proceed. For a similar case, see United States v. Oppenheimer (1916), though there the defense was the statute of limitations rather than insanity.

Ultimately, the question of whether or not murder charges are brought will be in the hands of the U.S. Attorney in Washington, and the District’s Attorney General. As things stand right now, though, it seems as though such charges would be on legally tenuous grounds.

Eugene Volokh points out that both the year-and-a-day rule and the finding of mental incompetence by the original jury would prohibit any prosecution.

It doesn’t seem clear to me at all. The question of mental competence is a medical determination, not a legal one. If (for example) the prosecution depended on whether Hinkley had hepatitis at the time in 1982, you would make that determination using current medical knowledge, not 1982 medical knowledge. Why would it be any different for evaluating his mental condition in 1982?

Also, there’s the question of whether he’s competent to stand trial today, regardless of whether he was sane in 1982. If he’s not, then no prosecution — and that determination would, again, be made using the current standards.

@Timothy Watson:

I’ve added an excerpt form Prof. Volokh’s piece to the post.

@DrDaveT:

First, Hinckley was not ruled incompetent to stand trial. Had he been, then there would have been no jury trial at all and he would have immediately been placed in the care of mental health professionals who would have attempted to treat him and bring him to the point where he was competent to stand trial. This is what happened with Jared Loughner, the man who shot Gabby Giffords and others in Phoenix in 2011. He was first determined incompetent to stand trial. After treatment, he was deemed competent enough to agree to a plea deal that will keep him in prison for the rest of his life.

The Hinckley situation is quite different. In his case, the jury determined that his mental state on March 30, 1981 was such that he could not be held legally responsible for his actions. If he is tried for murder in the Brady death, then it is his mental state on that day that will be the relevant issue, not his mental state today or at any point since the shooting.

@Doug Mataconis: Thanks for the clarification, Doug. I wasn’t clear in my comment that I was talking about two different kinds of determinations — the determination today about whether he is competent to stand trial today, versus the question of whether he can be held legally responsible for his 1981 actions.

Right — but the determination of whether his mental state on that day makes him legally responsible for his actions or not would be made (I would think) using best current medical knowledge, not 1981-era medical state of the art.

@DrDaveT:

I don’t see how medical science in 2014 is going to have anything new to say about HInckley’s menta’ state in 1981, especially given the fact that there is a whole host of psychiatric evidence that was developed in the run-up to the trial on that issue.

The best you could get would be some psychiatrist who would be reviewing 30 year old medical records and perhaps expressing a different opinion than the physicians who actually worked with Hinckley back then. I am not even sure that such an expert witness would even be allowed to testify at trial, and if he or she did their testimony wouldn’t strike me as carrying much weight compared to the contemporaneous examinations

@Doug Mataconis:

Really? I’d be shocked if they didn’t. Almost everything about how we deal with mental illness, including what counts as mental illness of various kinds, has changed in the last 30 years. Insanity is, to use an overworked phrase, “socially constructed” — it’s not an objective fact, but rather an attitude of the culture and the medical profession at a given time, informed by science but not determined by it.

The year and a day rule was the first thing I thought of when I heard about the homicide classification in the Brady case. If it still stands in federal law, and Hinckley was charged with a federal offense and tried in a federal court, I don’t see how he can be charged and tried again, even apart from the double jeopardy issue.

There is certainly the possibility that Brady’s injury may and I repeat may have resulted in his death a bit earlier than expected. But 33 years later trying Hinkley for murder would be a waste of money and resources.

@DrDaveT:

Cultural attitudes are not science and would not be admissible in court

@Ron Beasley:

At the moment, we’re dealing with two different issues. The M.E.’s classification of this as a homicide may well be correct, I don’t have the knowledge of the circumstances of Brady’s death or medical science to know whether it is right or wrong, but if you can make the argument that his death was caused by the medical conditions related t the paralysis and brain damage he suffered on March 30, 1981, then it may well be accurate to classify his death as a “homicide” instead of “natural causes.”

Whether this should be prosecuted is a different issue.

I do hope the medical examiner has solid evidence that Brady’s death can be attributed to him being shot by Hinkley.

Because I’m really not sure I like this at all.

Person gets shoved, falls down, and hits his head. He then dies 35 years later and the person who shoved him gets get charged with X.

@PJ:

That’s where the “year and a day” rule that Professor Volokh mentions comes in, though.

@DrDaveT:

Schizophrenia still exists. We just don’t call it demonic possession anymore. But it remains a horrible tragedy for its sufferers and their families.

Pandering to my inner cynic, “Ultimately, the question of

whether or not murder charges

are brought will be” determined by who can make the most political hay from it.

@Doug Mataconis:

You think not? Take a look some day at the history of child abuse prosecution. Acts that were considered normal parenting 100 years ago would get you locked up and your kids taken away in some jurisdictions today. The medical facts haven’t changed but the culture — including the professional culture among law-enforcement and social services workers — has.

Are you seriously claiming that what expert witnesses are likely to say about mental illness and the ability to distinguish right from wrong does not depend on cultural attitudes, and is the same today as it was in 1982?

@CSK:

That’s certainly true, but I’m having a hard time figuring out how it relates in any way to what I said above.

@DrDaveT:

You are completely missing the point I am making.

The testimony of people evaluating records created by others regarding the mental health of John Hinckley Jr in 1981-82 may not even be admissible at a trial in 2014.

@DrDaveT:

I was responding to your statement that insanity is a social construct rather than a real, diagnosable, treatable (in many cases) condition. Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and multiple personality disorder (rare) are real.

@Doug Mataconis:

No, I rather think it’s the other way around.

So who exactly do you think would be called upon to testify in a 2014 trial of John Hinckley Jr? I strongly suspect that they would be people who are alive today, and are part of the current medical and legal cultures. People whose opinions about what constitutes mental illness, incompetence, moral responsibility, legal culpability, etc. are significantly different from the opinions of comparable professionals in 1982. Which part of that is so hard for you to understand?

@CSK:

What do you mean by “rather than”? The two are not incompatible, but it’s hopelessly naive to think that there is an objective definition that is invariable over time, or that the one we have now is never going to change again.

Of course they are. So is homosexuality, but I don’t think anyone would claim that the prevailing medical/psychological view of that hasn’t changed since 1982, or that the view of medical and mental health professionals is wholly independent of the prevailing cultural views.

I am not making the argument you fear that I am making, nor denying the reality of anything.